Warning: This story contains graphic photographs. Viewer discretion is advised.

You must know Elizabeth “Lee” Miller. If you don’t, you soon will.

Often minimized as Edward Steichen’s model or Man Ray’s muse or Picasso’s object of affection — Miller was one of the most important, singular, photographers of World War II. Unfortunately, the photo most often associated with Miller is of her, not by her.

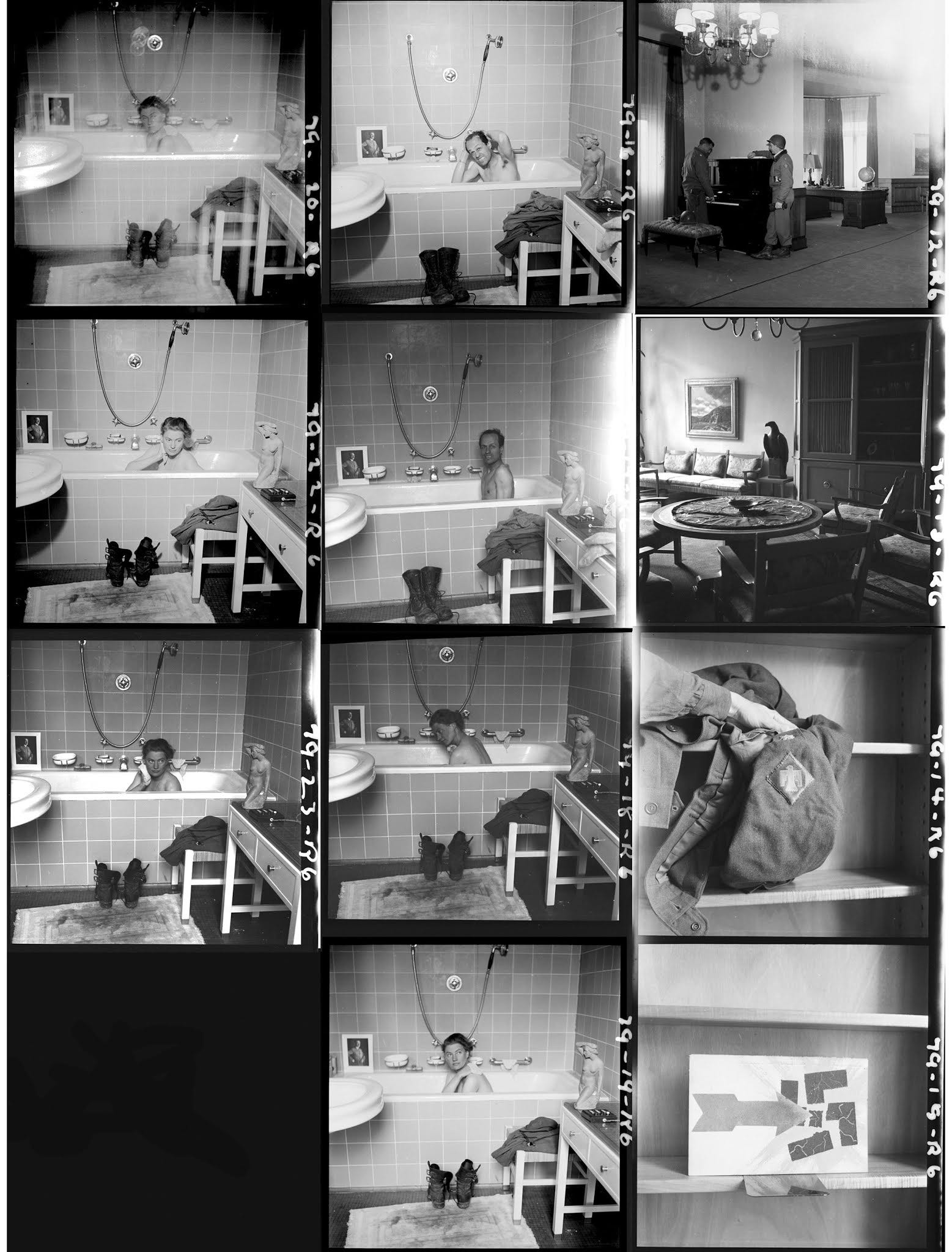

At first glance, it’s just a photo of Miller in a bathtub, then unsettling details emerge. But to fully understand this intriguing portrait of Miller, taken by David Scherman on April 30, 1945, context is essential.

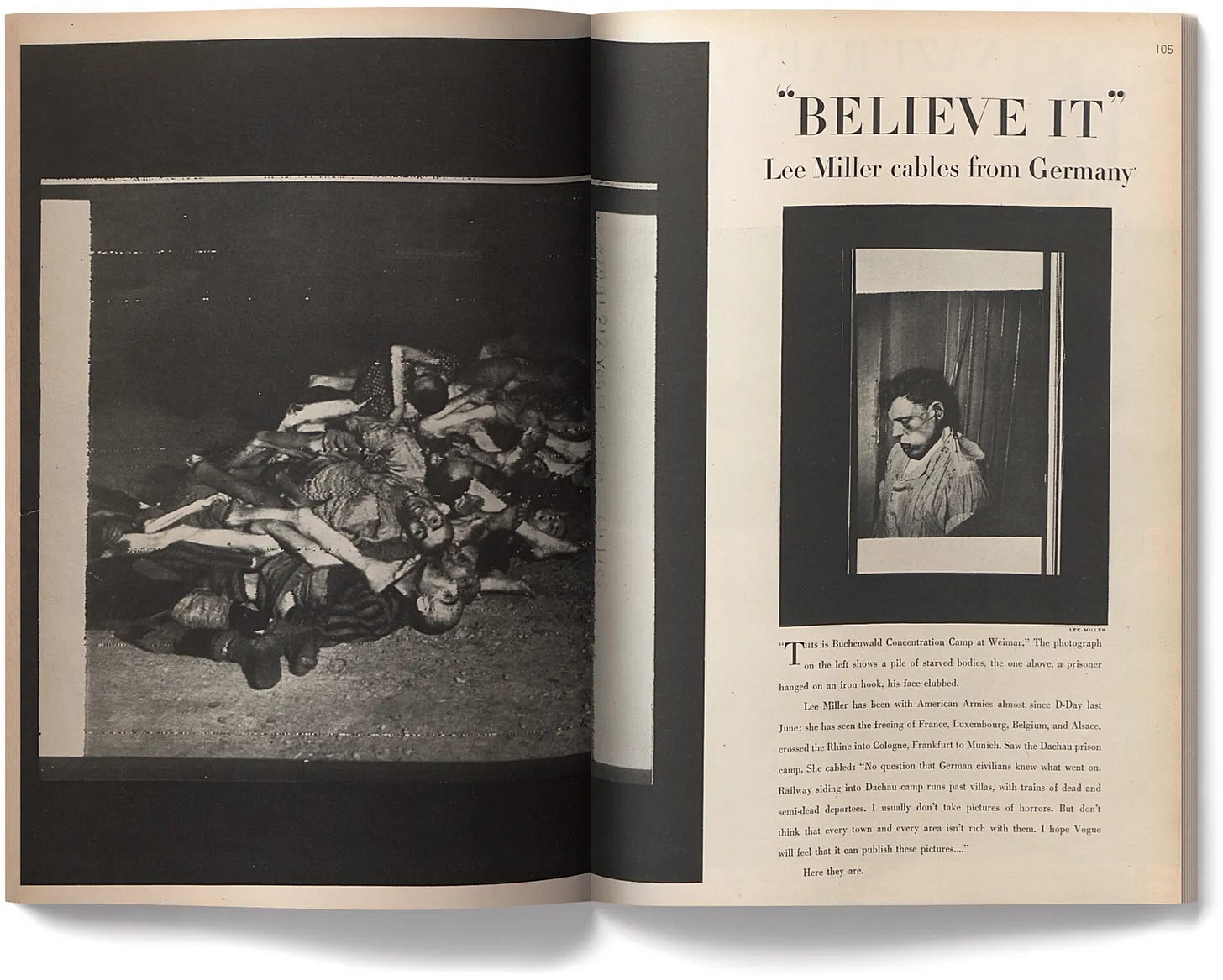

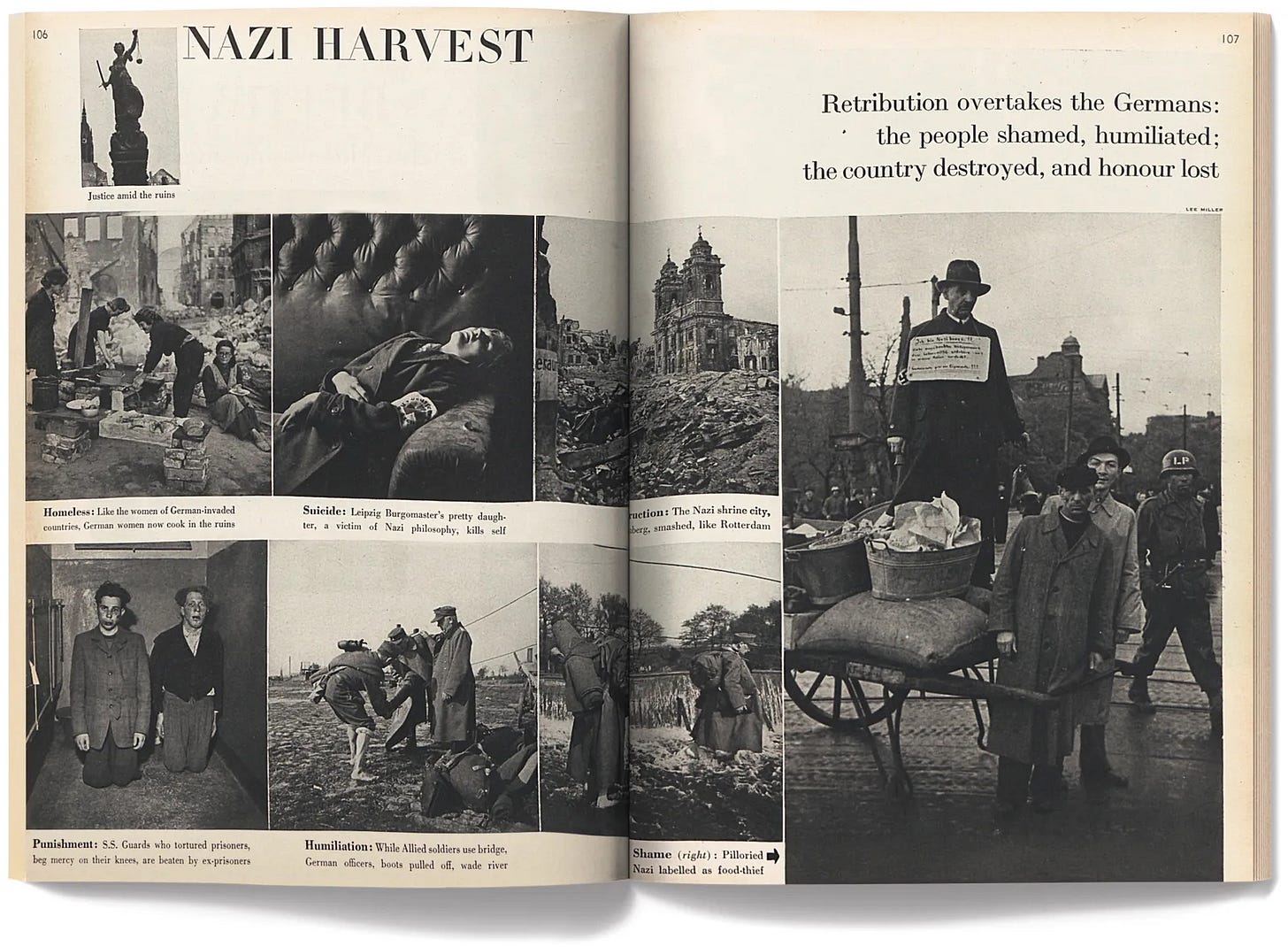

Just days before the photo in Hitler’s bathtub was taken, Miller, working for Vogue, and Scherman, working for LIFE, were among the first to document the atrocities at the Buchenwald concentration camp. Miller’s photographs are unflinching and devastating, layered and precisely composed.

“Lee’s previous experiences had given her a degree of emotional defense against the horrors of war and her main reaction was one of total disbelief,” Miller’s son, Antony Penrose, wrote in The Lives of Lee Miller. “Speechless and numb, she could not accept at first the enormity of the carnage and wanton slaughter.”1

Then, on April 30, 1945, Miller and Scherman entered Dachau. No past experience can shield one from the unimaginable.

Later that evening, Miller and Scherman found sanctuary at an American command post in Munich, in a nondescript apartment building located at 16 Prinzregentenplatz. Turns out, it was the home of Adolf Hitler.2

“The impression of ordinariness continued inside with furnishings and decor that could have belonged to anyone with a moderate income and no heirlooms. Only the swastika combined with the A. H. monogram on the silver gave it away as Hitler's house,” Penrose wrote.3

Here, Miller and Scherman took baths — their first in weeks.

“We were continually swapping cameras,” Scherman told John Loengard. “I used her camera for the photograph of her in the bathtub. Quite frequently, my pictures would come out in Vogue and her pictures would come out in LIFE.”4

Echoes of Capa and Taro.

The bathtub photo is complex and layered, amplified by the circumstances that preceded it. Most notable are her boots, covered in mud from Dachau, defacing Hitler’s pristine white rug. Then there’s the propaganda portrait of Hitler by Heinrich Hoffmann looming in the background, positioned next to the tub by the photographers. Miller’s body language mirrors the Venus statuette on the right.

“I took some pictures of the place and I also got a good night’s sleep in Hitler’s bed,” Miller told an interviewer. “I even washed the dirt of Dachau off in his tub.”5

Remarkably, April 30, 1945, was also the day Hitler committed suicide.

The contact sheet is revealing. It appears as though Miller moved the Hitler portrait slightly to the right when she photographed Scherman. The NPPA would not have approved.

The iconic bathtub portrait shoot was meticulously recreated for the biopic Lee, starring Kate Winslet, and beautifully photographed by Annie Leibovitz for Vogue. I love all the attention to detail. No way they used a tripod though.

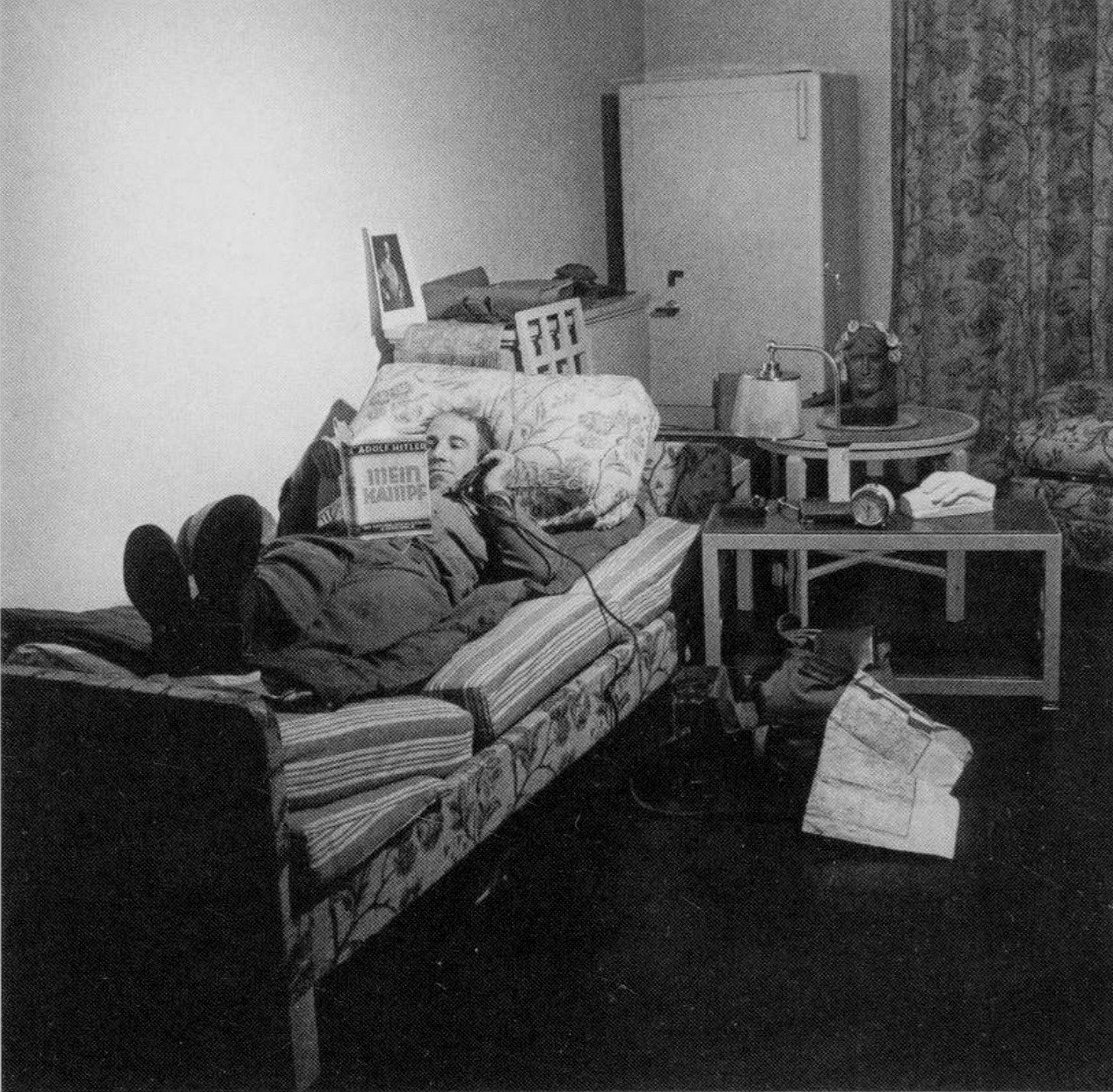

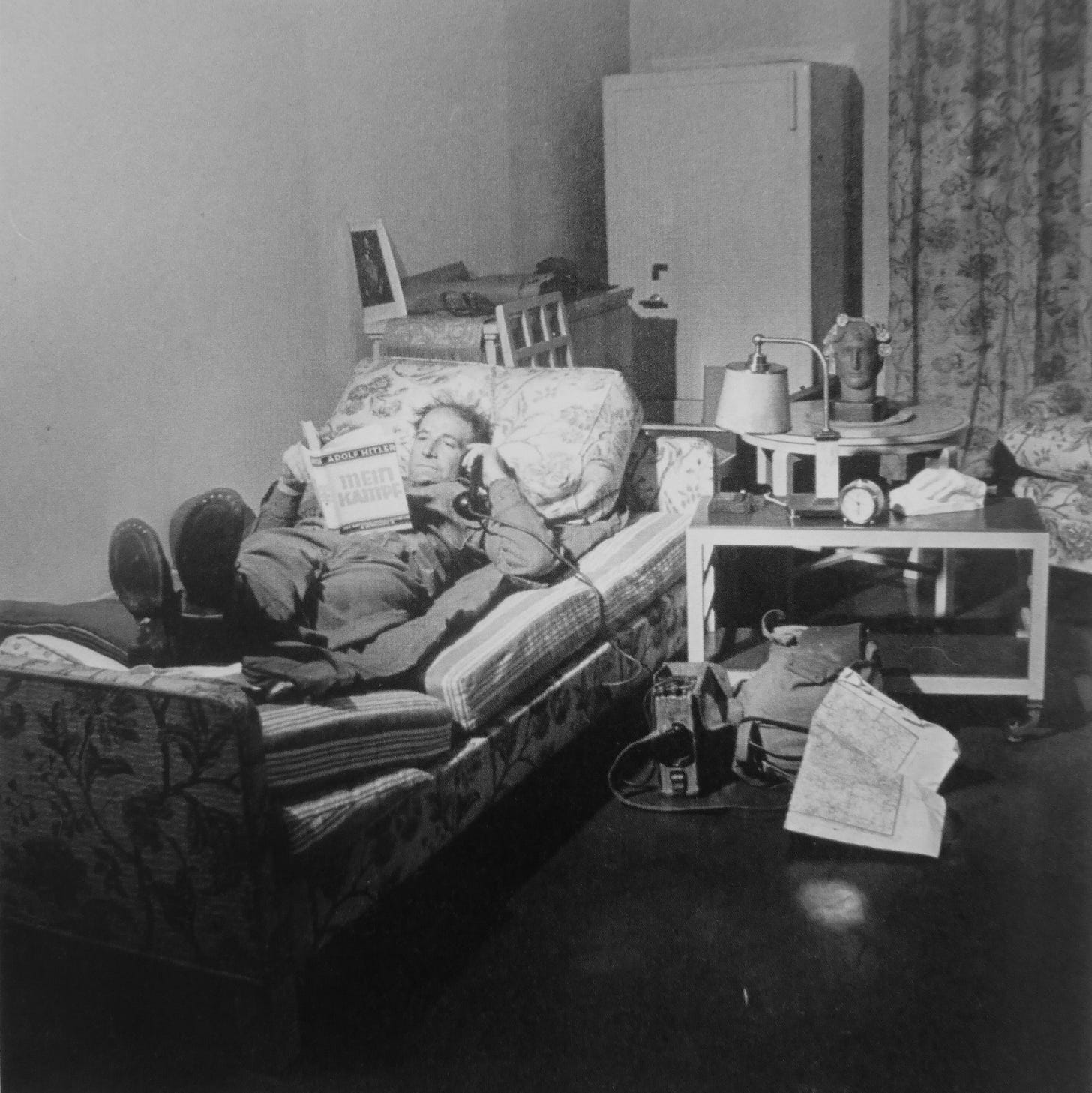

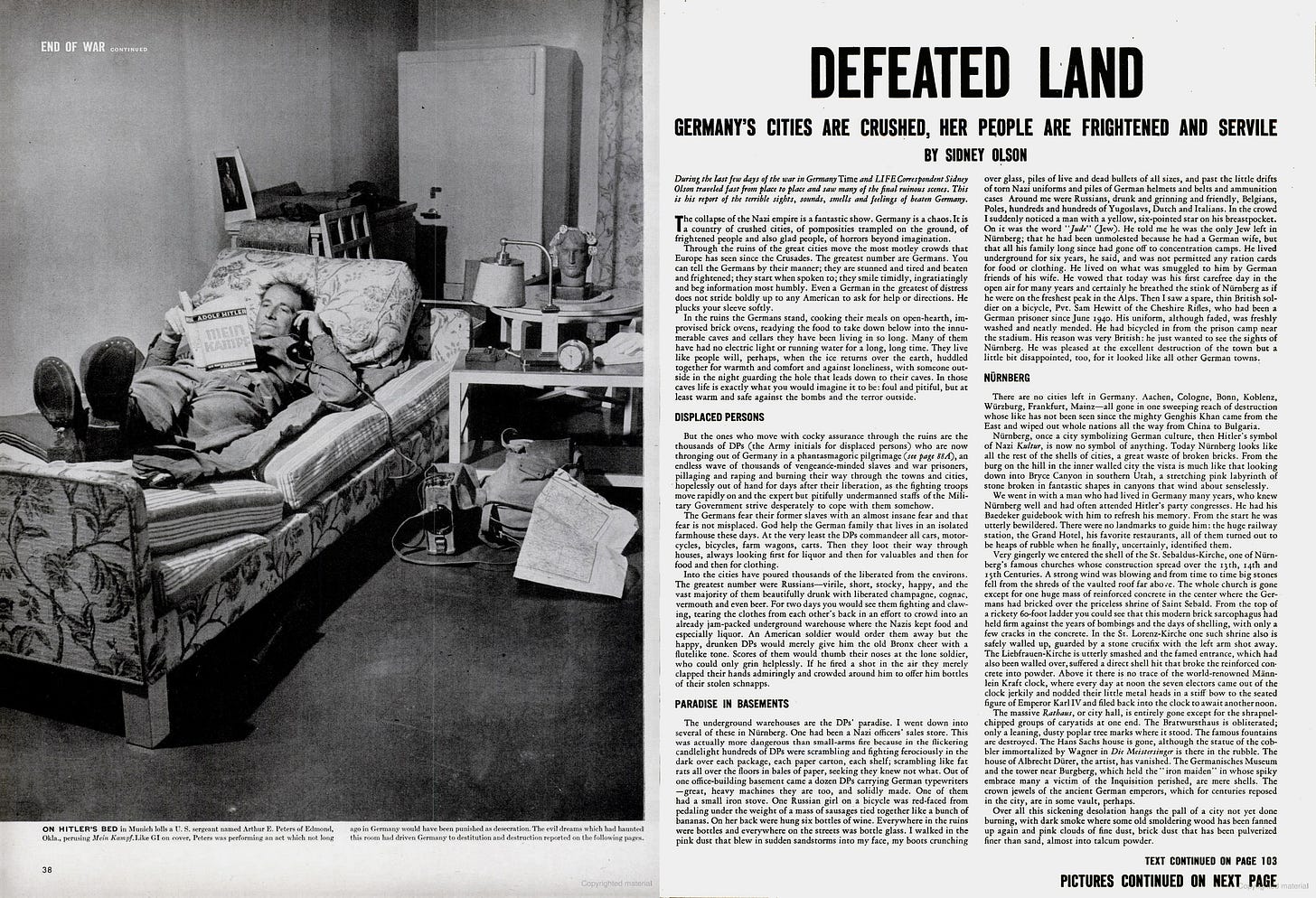

The bathtub wasn’t the only photo they staged in the Führer’s apartment. Miller and Scherman asked one of the soldiers of Rainbow Company to pose on Hitler’s bed with a copy of Mein Kampf and pretend to talk on the phone.

Their photos are nearly identical. Hoffman’s propaganda portrait of Hitler, which also appears in the bathtub photo, can be seen in the background.

LIFE published Scherman’s photo with the caption: ON HITLER’S BED in Munich lolls a U.S. sergeant named Arthur E. Peters of Edmond, Okla., perusing Mein Kampf.

The duo then walked a few blocks over to Wasserburgerstrasse 12 — the home of Eva Braun.

“We found Eva Braun's house, and we moved in there and lived there for four or five days before the Americans discovered it,” Scherman recalled. “We got quite a few amusing souvenirs of Eva's and Adolf's.”

Miller wrote, “it was comfortable, but it was macabre…to doze on the pillow of a girl and man who were dead, and to be glad they were dead.”6

Miller shipped her film and sent a telegram to British Vogue editor Audrey Withers with a plea: “I IMPLORE YOU TO BELIEVE THIS IS TRUE.” Her photos appeared in the June 1945 issue.

Miller's past, spanning her traumatic childhood, her life in the fashion industry, and her exploration of surrealism, uniquely shaped and influenced her approach to war photography. The following photos are good examples of that.

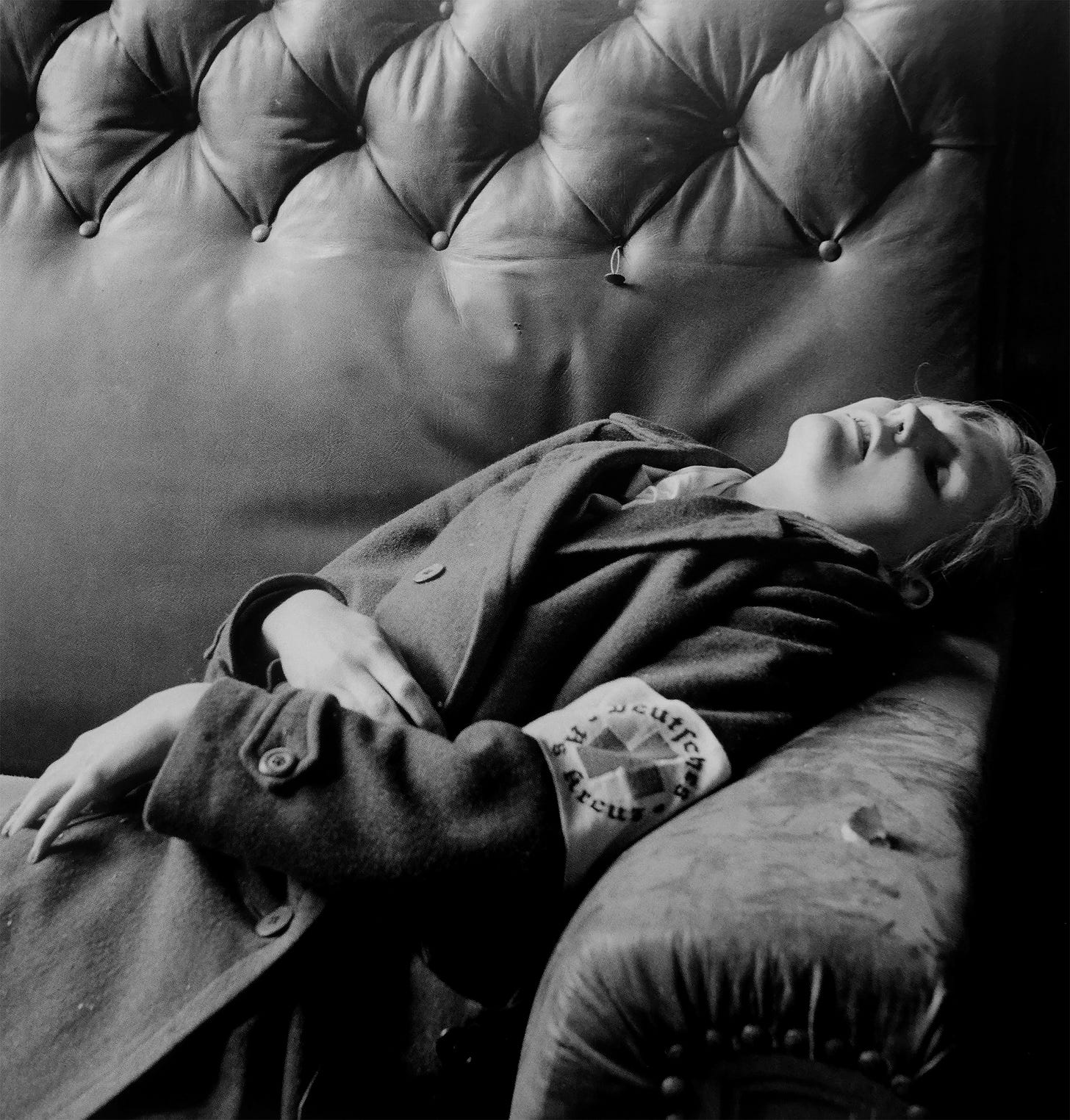

To avoid capture by American soldiers, many Nazis resorted to suicide. In Leipzig City, the deputy mayor and his family popped cyanide pills, leaving their lifeless bodies scattered across his office. LIFE photographer Margaret Bourke-White arrived first and captured the macabre crime scene.

Then Miller showed, and shot this surreal, uncomfortably intimate photo of the deputy Mayor’s daughter. My eye is immediately drawn to the loose button on the couch.

The difference between the two versions is stark and obvious — Miller’s past in fashion seeping into her choice in composition and focus on details. Miller later said that the daughter had “extraordinarily pretty teeth.”7

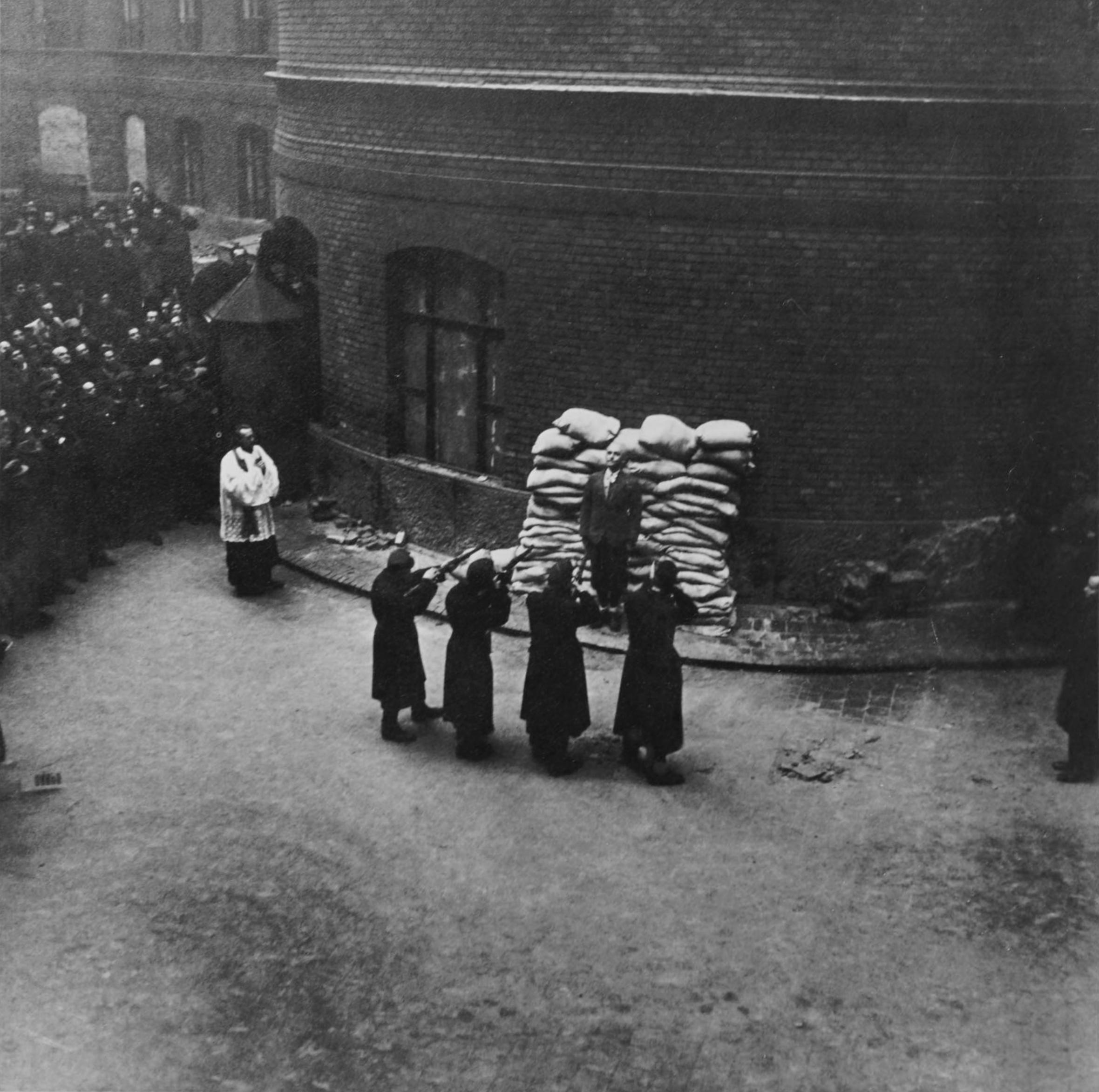

After the war ended Miller traveled alongside LIFE photographer John Phillips. On January 10, 1946, they documented the execution of László Bárdossy, the fascist ex-Prime Minister of Hungary. Phillips captured this image, just after the execution by firing squad.

“He wore the same plus-fours, tweed suit, ankle high shoes with white socks turned over the edges as when he'd been arrested,” Lee wrote in her unpublished manuscript. “The impact threw him back against the sandbag and he pitched to his left in a pirouette, falling on the ground with his ankles neatly crossed.”8

This photo of Miller’s is my favorite. It’s artful and restrained, a testament to her brilliance as a photographer — not someone’s muse.

Antony Penrose, The Lives of Lee Miller (New York: Holt, Rinehart and Winston, 1985), 139.

Jane Livingston, Lee Miller, Photographer (London: Thames and Hudson, Inc., 1989), 89.

Antony Penrose, The Lives of Lee Miller (New York: Holt, Rinehart and Winston, 1985), 140.

John Loengard, Life Photographers: What They Saw (New York: Bulfinch Press, 1998), 113.

Carolyn Burke, Lee Miller: A Life (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2005), 298.

Antony Penrose, The Lives of Lee Miller (New York: Holt, Rinehart and Winston, 1985), 142.

Carolyn Burke, Lee Miller: A Life (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2005), 254.

Jane Livingston, Lee Miller, Photographer (London: Thames and Hudson, Inc., 1989), 95.

Wow, I can see why she begged to be believed, because it's all so beyond the periphery of "normal" - all of it, damn

Thank you for restacking this article. Lee Miller was perhaps one of the most important photographers of the era.