War Is The Most Violent Color

“I became a body without a soul."

It’s impossible to scroll past this photo by Ali Jadallah. The splash of color emerging from the colorless, apocalyptic aftermath of an Israeli airstrike demands attention.

The details are devastating: the screaming mother, the barefoot child, the hand, and something incredibly meaningful I didn’t notice right away — that’s a yellow curtain, not a yellow blanket.

Jadallah made this photo October 23, 2023, twelve days after his father, two brothers, and sister were killed in an Israeli airstrike. Only his mother survived.

“The whole world died suddenly,” Jadallah wrote in The Economist. “There were no feelings, there were no colors, there was nothing. I tried to call my brothers but I knew they were under the rubble. We never found my sister’s body.”

“I became a body without a soul.”1

Jadallah's ability to keep photographing amidst it all is a miracle.

Color is critical in Jadallah’s photo of the mother and child in the yellow curtain. Color is equally critical in these heart-wrenching photos from a child’s bedroom in Nir Oz, a kibbutz near the Gaza border that was brutally attacked by Hamas terrorists.

Sergey Ponomarev, working for The New York Times, was one of several photographers given a tour of the massacre sites by the Israeli military. Ponomarev’s composition is symmetrical, his palette subdued.

Associated Press photographer Francisco Seco centered the blood-stained mattress, omitting the clock and the handmade heart on the door. The color in Seco’s photo is vivid, unsettling.

VII’s Ron Haviv, whose photos appeared in the New York Post, included the clock and heart but omitted the blood-stained pillow on the ground. A heartbreaking detail can be seen on the far left of Haviv’s photo: a child’s play kitchen.

EPA photographer Martin Divisek’s version offers a fuller view of the kitchen playset.

This version is by Reuters’ photographer Amir Cohen.

Haaretz staff photographer Moti Milrod documented the scene positioned furthest to the right. While the empty white space is a distraction, Milrod’s photo offers the clearest view of the play kitchen set and the art on the walls.

These photos stirred some dark memories from when I was a picture editor at The New York Times. During the Gaza War in 2009, I was confronted with some of the most graphic photos I’d even seen. I remember a horrific photo of three children killed in an Israeli airstrike that I advocated publishing on the international section front (which was in color). The News Desk, a group of editors that makes the final call on these kinds of decisions, disagreed — the photo, in color, was too gory for publication. But inside the paper, in black and white? That’s a different story. Blood, in black and white, is less…bloody. We published the picture.

That difference is worth considering. It brings to mind a handful of moments in the history of war photography that have been captured simultaneously in both color and black and white.

In 1968, Tim Page captured this scene of a boy mourning the loss of his sister, gunned down by U.S. helicopters during the Tet Offensive.

Magnum’s Philip Jones Griffiths also documented the tragic moment, but in black and white. Is the color a distraction? Or does the color of the truck emphasize the brutality of the scene?

Gritffiths was standing just to the right of Page, enough so that the boy is more-clearly separated from the background. A small, but significant compositional tweak. His book, Vietnam, Inc., is a masterpiece.

LIFE magazine photographer Larry Burrows was prolific shooting color during the Vietnam War. Burrows made this photo of a woman crying over the remains of her husband who was killed during the Tet Offensive. Burrows’ attention to detail is extraordinary.

Legendary AP photographer and photo editor Horst Faas documented the same scene, but a different moment.

Another compelling example is this moment from the Bosnian War in 1995. Ron Haviv made this powerful photo of a Bosnian soldier, Senad Medanovic, mourning the loss of his family upon returning to his home, decimated by Serbian forces. Haviv’s color is lush, the converging lines create tension throughout the frame.

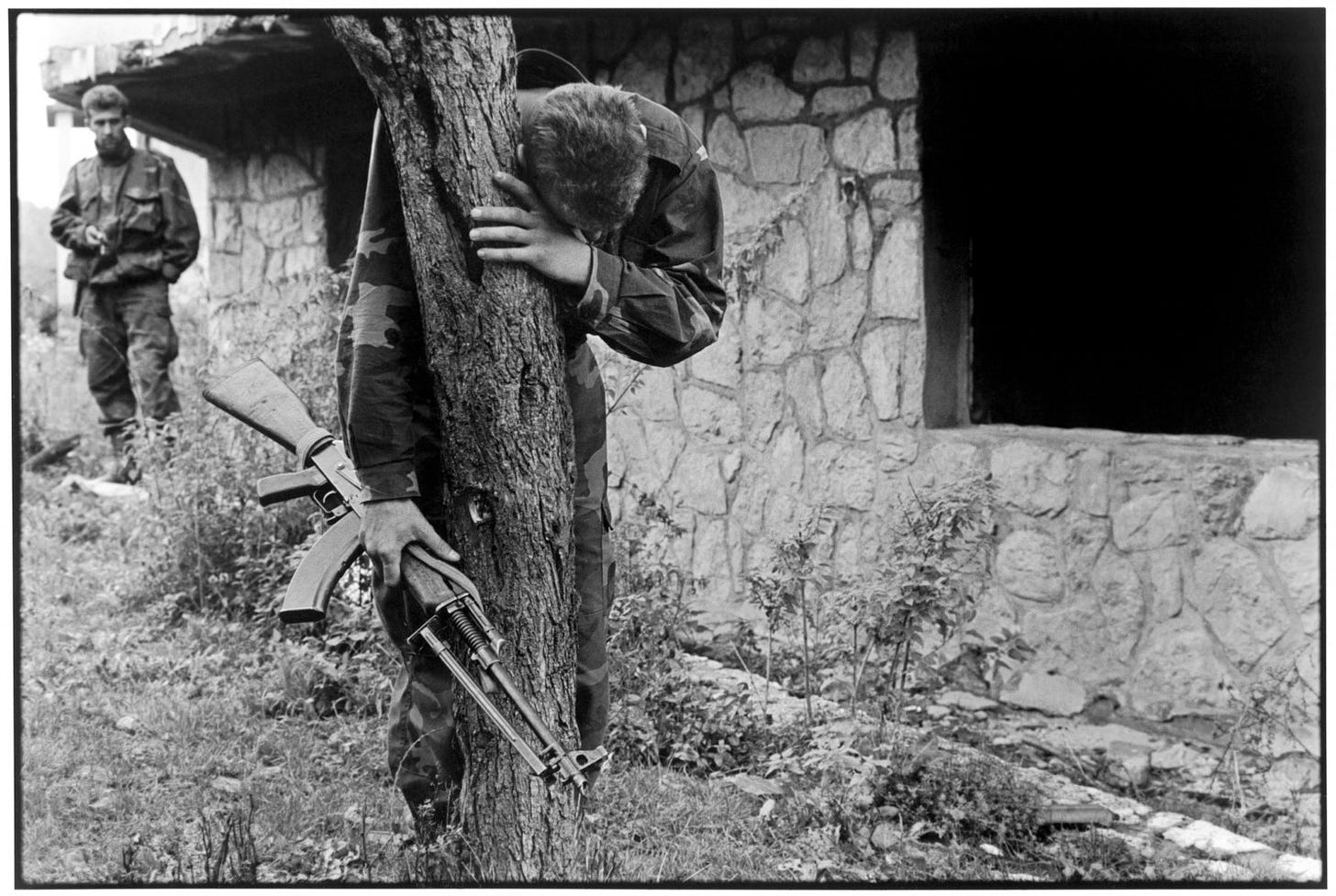

Magnum’s Gilles Peress immortalized the scene as well, with a slightly longer lens positioned just to the right of Haviv. The absence of color intensifies the rawness of the moment.

During the Chechen War in 1995, the AP’s David Brauchli photographed a woman walking past a victim of a Russian airstrike in Grozny. Is the bright blue garage door a distraction or a compositional element that balances the frame?

A split second later, James Nachtwey, working for TIME, made a similar frame, but in black and white.

Fast forward twenty years and film stock no longer dictates whether a photographer is working in color or black and white. Even though Nachtwey has transitioned to digital, his decision to shoot in color or black and white remains deliberate (I was his editor at TIME from 2010-2014).

Back to those horrific photos from the child’s bedroom in Nir Oz — would the images be as powerful in black and white? What about Jadallah’s photo of the mother and child in the yellow curtain? Perhaps. But that decision should be meaningful, intentional, and be determined by the photographer — not the photo editor.

An unfortunate example is how Mohammed Abed’s photo was used in the Opinion section of The New York Times.

Not only was Abed’s photo harshly-cropped, it was converted to black and white. Why? Does that make it more…opinionated? Look at the original and appreciate what was lost. Every inch of Abed’s photo has meaning, even the fly, and should be seen.

All of this is quite trivial given that, as of today, 36 journalists have been killed during the Israel-Gaza War.

Following the deaths of Ali Jadallah’s family, The New York Times’ Yousur Al-Hlou asked the IDF if his family’s apartment building had been targeted. They wouldn’t say, only issuing a brief statement: “We’re at war.”

Dara Coker, “Ali Jadallah has lost four relatives in Gaza. He’s still taking pictures,” The Economist, (October 27, 2023).

I have a naive question. I've seen the "movies" of course, but never been in war experience. I'm curious what the logistics of a war photographer like that you can get multiple POV's of the same event taken seconds (and mere inches) apart? Do the photographers generally travel in groups? Do they rely on local vans/busses to drive them around?

Thank you for posting this reflection. I've rarely read such a close, and meaningful reading on composition and color as it relates to war and suffering. It stopped me in my tracks today, and I'm grateful for that.