The Prisoners of Wars

Photographs as evidence; photographs as propaganda.

On December 8, 2023, after documenting clashes between Israeli soldiers and Hamas militants in Gaza, Haaretz photographer Moti Milrod happened upon a grim scene — dozens of blindfolded and bound Palestinian prisoners, packed into the back of an Israeli military vehicle.

The details are disturbing. Two women and one child can be seen among the sea of shirtless men, some bruised and bloodied, some with numbers scrawled on their backs.

“It was a a real war zone,” Milrod told me. “As the tour started it was quite calm, but then we witnessed an exchange of fire with three militants in an alley where tanks and soldiers were in position. All I could think of was taking pictures, and I must admit that it felt quite safe being alongside the Israeli soldiers.”

“I was lucky that truck of detainees broke down next to the jeep that took us back to Israel,” Milrod added.

That was unplanned. Milrod’s photo became evidence, not propaganda.

Reuters photographer Yossi Zeliger captured the same scene from a slightly different angle.

In accordance with embed rules, Milrod’s and Zeliger’s photos were reviewed and subject to approval by the Israel Defense Forces (IDF), a condition for journalists to enter Gaza. Milrod said that the IDF “didn’t disqualify” his photos, which tells me they didn’t notice the damning details or maybe just didn’t care.

Yet for some inexplicable reason, The Washington Post published a different image taken by Zeliger that leaves out the most important detail: the blindfolded woman (in purple).

Similarly, The New York Times published a ground level photo taken by Milrod, which obscures and sanitizes the situation. Neither were good decisions by the photo editors.

Photographs of prisoners of war are ambiguous. While some people may perceive an image as dehumanizing and cruel, others could interpret it as a symbol of victory — an apt description of this photo of Palestinian prisoners in Gaza.

The original source of the photo remains unknown. N12, an Israeli television station, first shared it on Telegram December 12, where it quickly went viral across both pro-Israeli and pro-Palestinian channels. Something feels off about the photo. The men in the foreground, illuminated by a floodlight in front of the IDF soldier, seem artificial. If faced with the decision to publish, I wouldn’t.

The blindfolded, bound prisoners and the looming dirt embankment, draw striking parallels with Micha Bar-Am’s 1973 image of Egyptian prisoners during the Yom Kippur War.

The composition is deliberate, restrained. Bar-Am wrote that while he embraced Robert Capa’s oft-quoted mantra, “If your pictures aren’t good enough, you aren’t close enough,” he also cautioned, “If you’re too close, you lose perspective.”1

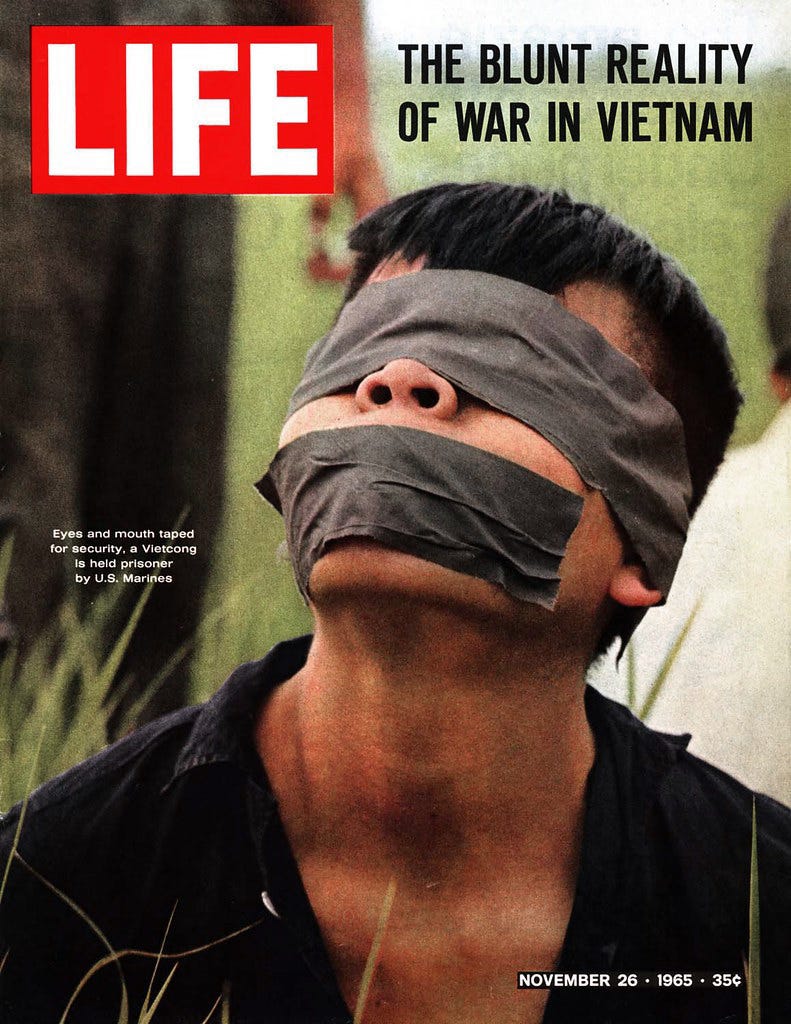

The blindfold is a dark motif in photos of prisoners of war throughout history — particularly during the Vietnam War.

LIFE magazine photographer Paul Schutzer made one of the most iconic prisoner of war photos in Vietnam in 1965, illustrating the “blunt reality” of the war. Hell of a cover.

An alternate version of Schutzer’s photo is equally compelling. The inclusion of the soldier smoking in the background and the dehumanizing name tag around the prisoner’s neck add nuance and context.

“Paul got carried away with all the emotions that happen in war, and he was right in there with the soldiers in battles,” Schutzer’s wife, Bernice Galef, told TIME. “He saw everything; he saw the fatigue of the American soldiers, their fear, the prisoner’s fear.”

Less than two years after making those photos, Schutzer was killed while covering the Six Day War.

Associated Press photographer Eddie Adams, renowned for his Pulitzer Prize-winning photo, “Saigon Execution,” captured an astonishingly similar scene.

The environment, the masking tape, the name tag, and the soldier in the background — all identical. However, Adams opted for a lower angle, from the prisoner's perspective, adding drama and compassion to the photo.

Another AP photographer, Henri Huet, made this image of two captured Viet Cong guerrillas in 1966. The casually smoking U.S. soldier is proof of Huet’s discerning eye.

“Henri goes to war the way others go to the office,” Horst Faas, the AP’s chief photographer in Saigon, once said.2 Huet was one of four photographers who were killed when their helicopter was shot down in Vietnam on February 10, 1971.

Faas photographed South Vietnamese soldiers questioning Viet Cong prisoners in 1962. The pruned, bound hands of the wet prisoner are an interesting detail. I also appreciate the ever-so-slight tilt.

The soldier's gun, his body language, and the serene landscape evokes Robert Capa's photo of a Nazi soldier surrendering during the Battle of the Bulge in 1944.

Capa, who co-founded Magnum Photos three years later, was covering the World War II for LIFE. “The Germans were tough in their well-prepared fortress, but not so tough that they fought to the last German — only to the first American that got close enough to be dangerous,” Capa wrote. “Then they threw up their hands, shouted ‘Kamerad!’ and asked for cigarettes.”3

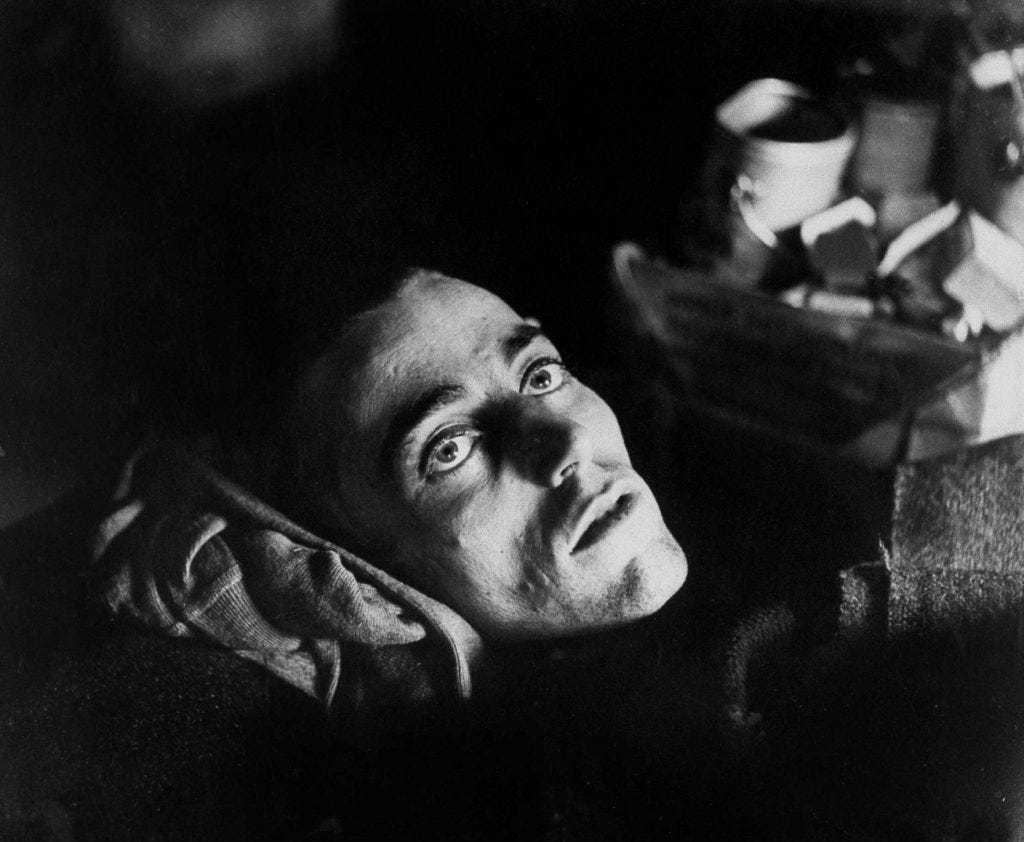

Americans were also held captive during World War II. LIFE’s John Florea made this haunting portrait of a U.S. soldier in a Nazi prison camp in Limburg, Germany.

“I looked over and I saw this face, just looking up. He was in a daze,” Florea recalled. “He was starving to death, and rather than say anything to him, I turned my camera toward him, went up a little closer and shot pictures of that staring face that I see — you don’t know how many times I see those pictures in my mind. I wanted to show how the Nazi bastards — what they did to our guys. It was terrible.”4

War is terrible, and few images capture the terror experienced by a prisoner of war as profoundly as this photo by Jean-Marc Bouju.

In 2003, Bouju photographed a hooded Iraqi prisoner of war embracing his 4-year-old son in a detention center operated by the U.S. military.

“The whole scene was surreal,” Bouju told TIME in 2013. “My daughter was the same age as the child in this photo. I look at her today and wonder what happened to that boy. I wonder why we were at war. What was accomplished? Ten years. An army of dead, wounded and mentally destroyed people. Maybe they, too, are wondering: why? I remember, and I wonder.”

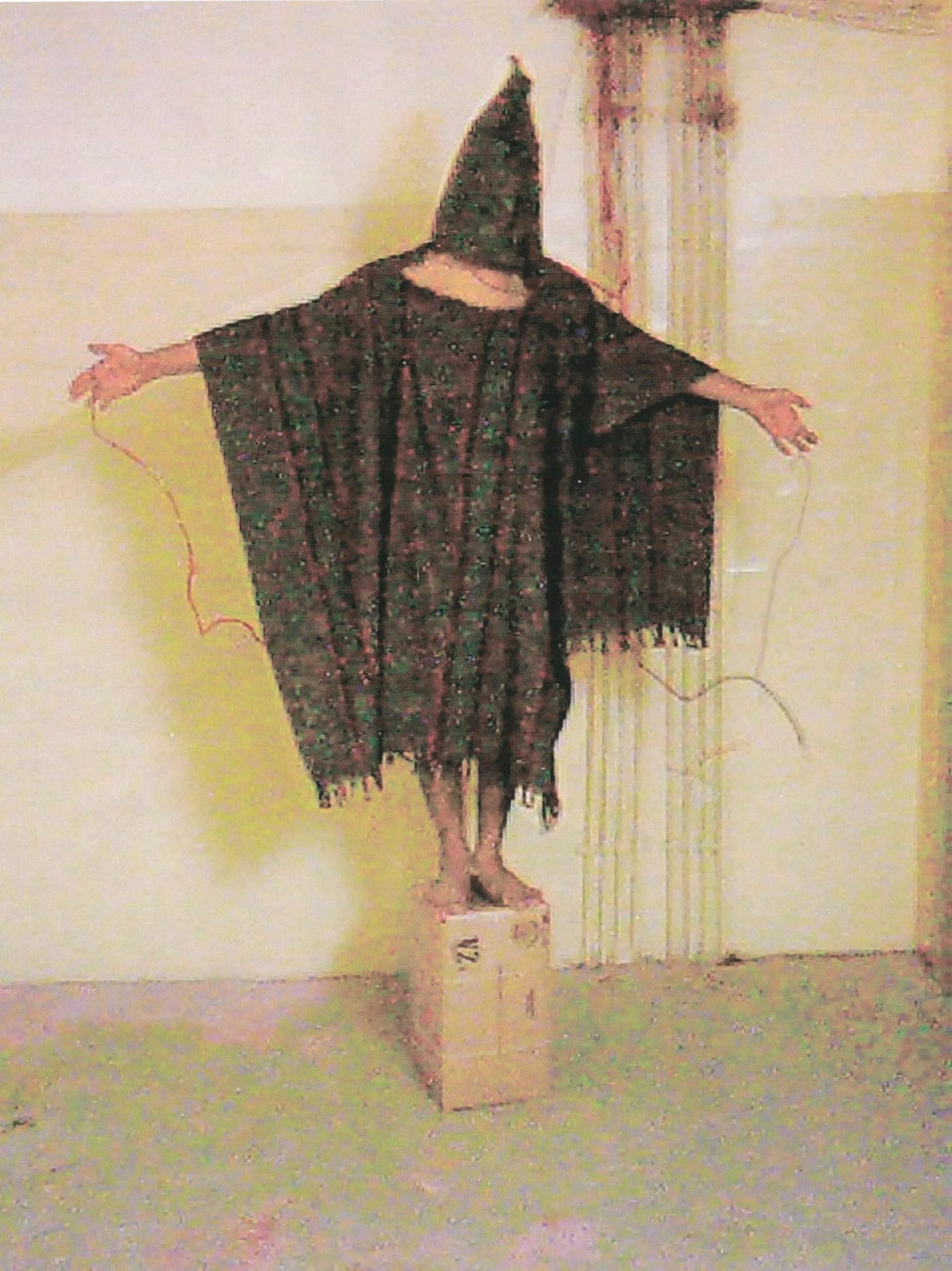

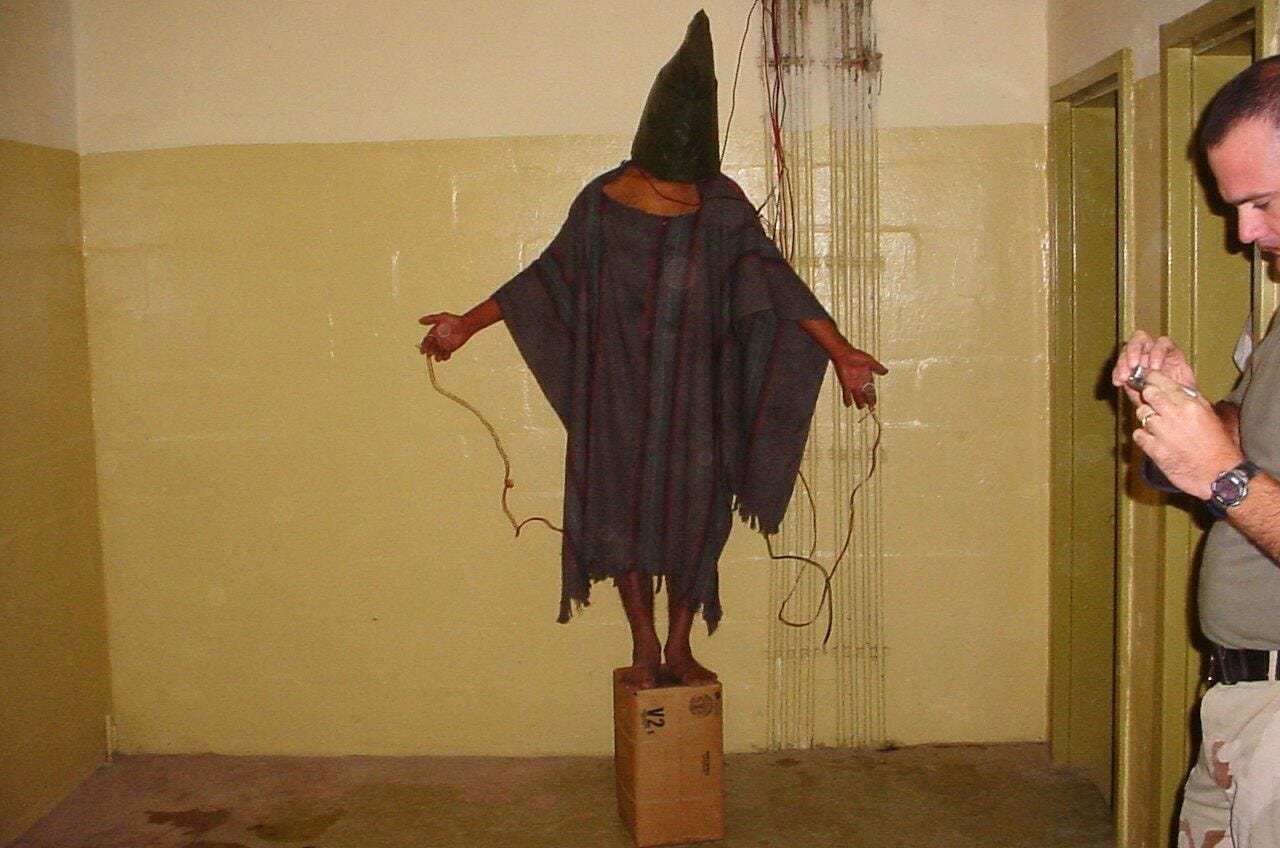

Some of the most disturbing photos of prisoners of war were never meant to be widely seen. The most infamous of which are these photos of a victim of torture and abuse at Abu Ghraib prison in Iraq, first published in The New Yorker in 2004.

This photo was taken at 11:01 p.m., November 4, 2003, by Staff Sgt. Ivan Frederick with a Mercury Peripherals Deluxe Classic Cam. The “Hooded Man” in the photo, Abdou Hussain Saad Faleh, was told by his American captors that he’d be electrocuted if he fell off the cardboard box. It’s arguably the most famous image from the Iraq War.

Three minutes later, Specialist Sabrina Harman took this photo with a Sony FD Mavica. Frederick can be seen on the right looking at the photo he’d just taken.5

Much like the anonymously-made photo of the Palestinian prisoners above, the “Hooded Man” photo acted as evidence and propaganda.

Some prisoner of war photos were hidden from the public for decades. In 2002, Naval Officer Michael W. Pendergrass made this photo of a prisoner at Camp X-Ray in Guantanamo Bay.

The sensory deprivation is shocking and hardly seems real. Pendergrass’ photo wasn’t seen until 2022, when it was finally published by The New York Times.

“With the shackles on, it was easier to transport them by carrying them,” Pendergrass told the Times.

The American flag is framed perfectly in the background. That was unplanned.

Alexandra Nocke, ed., Insight Micha Bar-Am’s Israel (Köln: Walther König, 2011), 10.

Richard Pyle, “Saigon Quartet,” Vanity Fair (December 1999): 278.

Robert Capa, Slightly Out of Focus (New York: Henry Holt and Company, Inc., 1947), 162.

John Loengard, Life Photographers: What They Saw (New York: Little, Brown, and Company, 1998), 169.

Errol Morris, Believing is seeing: observations on the mysteries of photography (New York: The Penguin Press, 2011), 90.

Incredibile Patrick. Dramatic, but your narrative makes of this article an essay. An applause.

I’ve often heard the “one death is a tragedy a million a statistic” (Stalin?) thing, but I still don’t understand why my gut turns inside out when I see the images of a single person taped up and rendered helpless, but whole trucks or fields full of people in the same condition doesn’t hit my heart the same way. I think it’s a failing on my part but maybe a common one. Thank you for this, as always, your writing and perspective are so valuable.