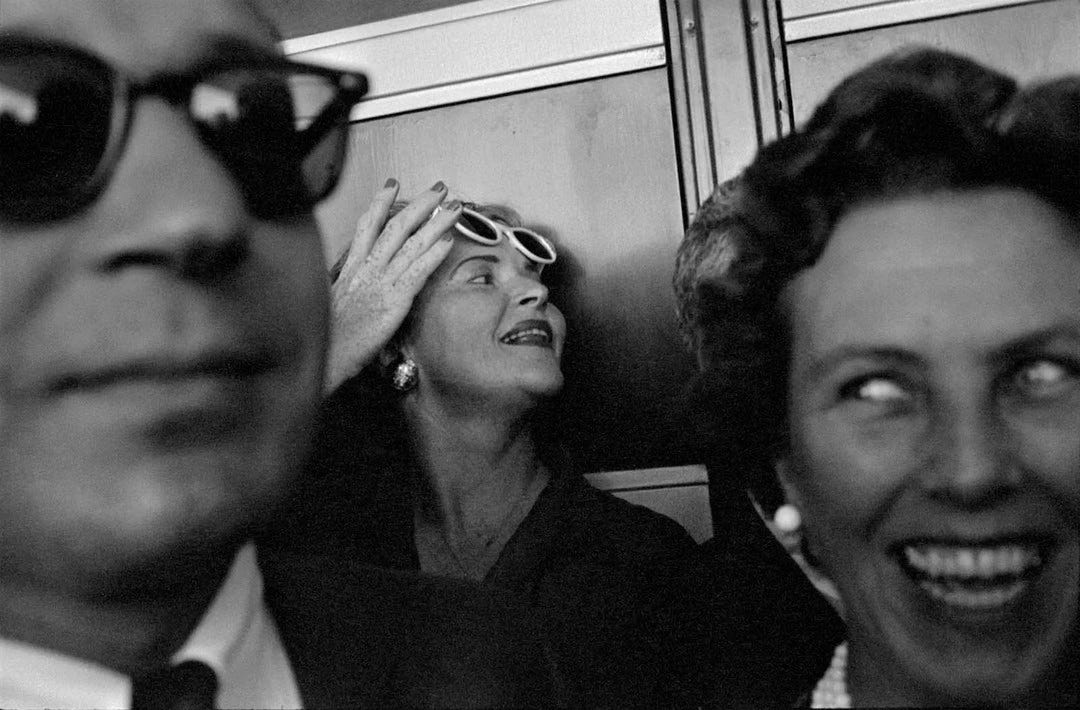

July 11, 1960: The Democratic National Convention in Los Angeles was in full swing and a no-name street photographer was hustling through the smoke-filled crowd of power brokers and politicians, making pictures like it was Madison Ave.

Garry Winogrand burned through 140 rolls of black and white film at the convention in his signature “people watching the parade, not the parade”1 style—frantic yet deliberate, thoughtfully layered and meaningful. Only one photo saw the light of day (John F. Kennedy, above), while the rest stayed hidden for decades, until their discovery in Winogrand’s archive at the Center for Creative Photography in 2011 and subsequent publication in The New York Times Magazine.

It was pre-New Documents Winogrand at his best…

Winogrand’s photo of Kennedy accepting his party’s nomination symbolized a turning point in politics—the birth of the television president. These days, photographers at political conventions are part of the crowd, there to document, for the most part, a TV performance. Access has dwindled to the point of nonexistence.

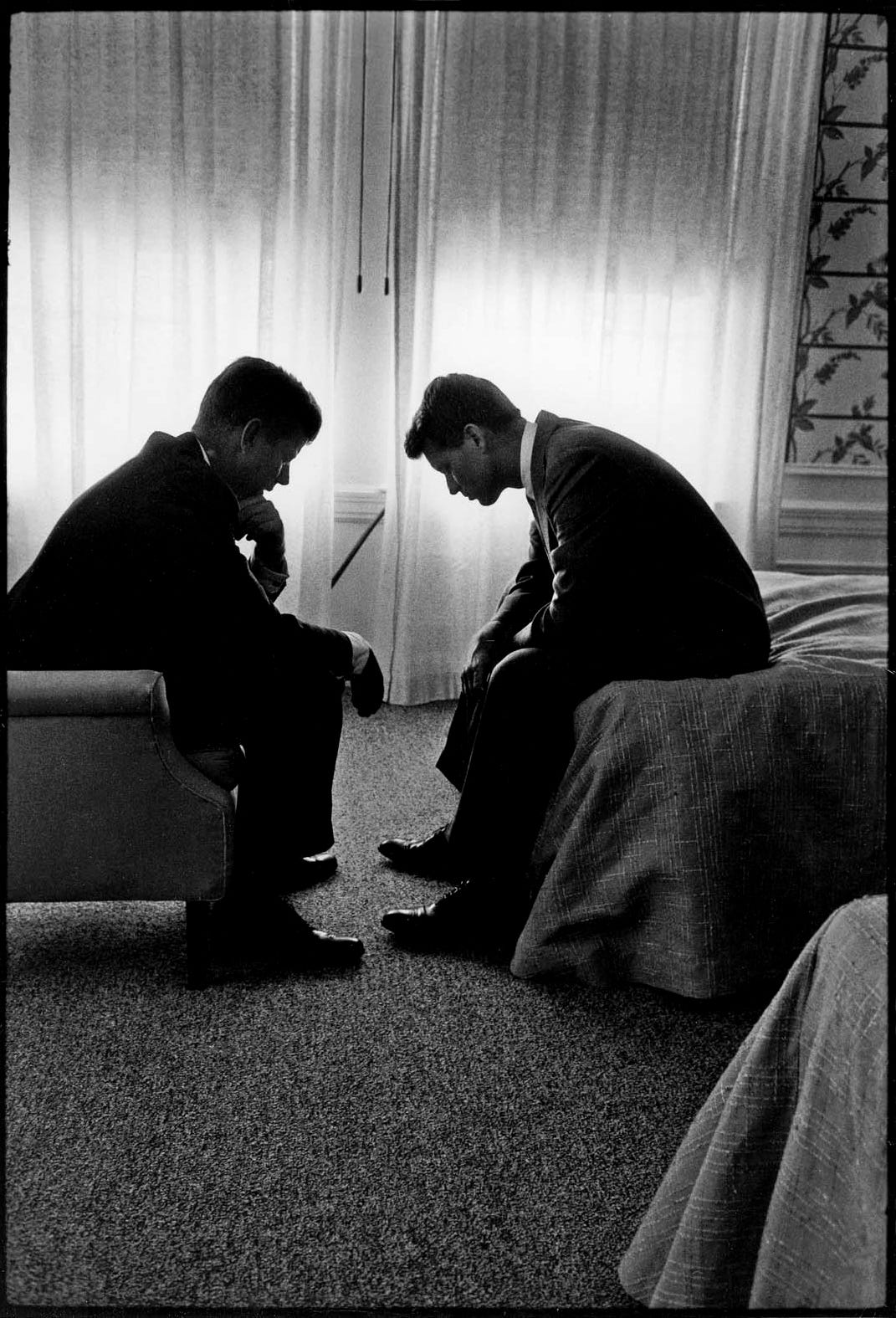

Few photos exemplify access like this gem by LIFE magazine photographer Hank Walker: Kennedy and his brother Robert deep in conversation in a hotel room during that same convention in 1960. It’s one of my all-time favorite political photographs. Access to an authentic moment like this is a photojournalist’s dream.

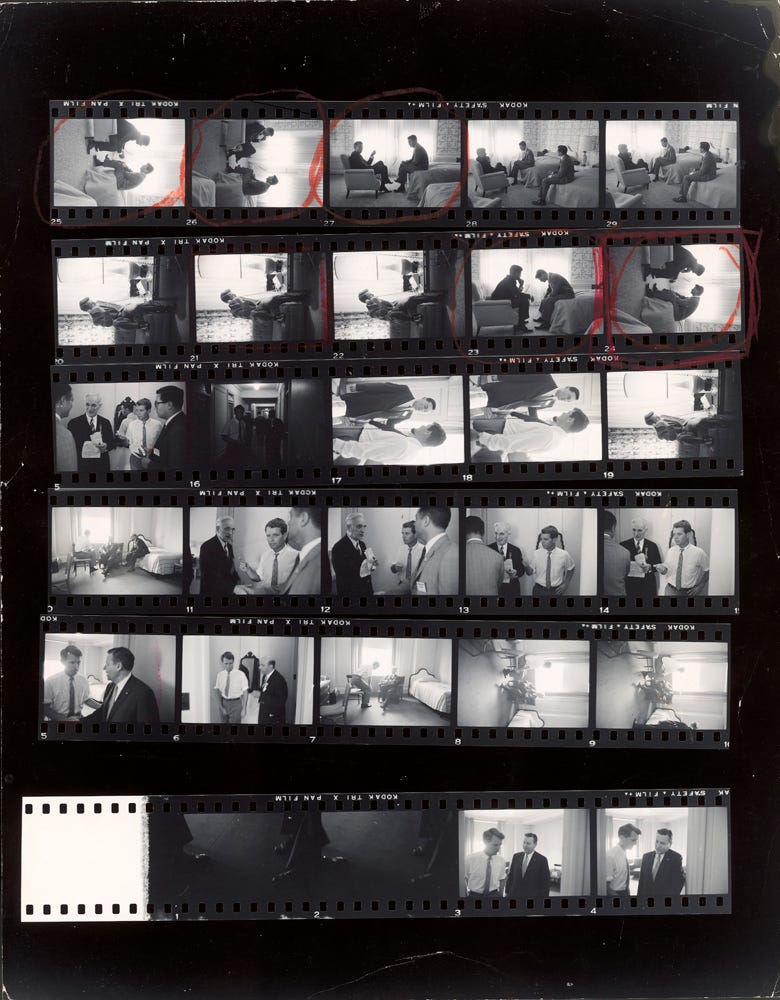

“The brothers talked very quietly, and Jack told Bobby who he was going to choose as Vice President,” Walker said in a 1994 interview. “I only made one picture in there, and then I waited outside for Bobby to come out. When he did, he was furious.”2

Walker’s contact sheet proves he made way more than just one picture—he wasn’t escorted in and hurried out in 30 seconds. Walker was allowed to work it. Notice how at first he’s shooting horizontally (frame 23), then rotates his camera and makes the one (frame 24).

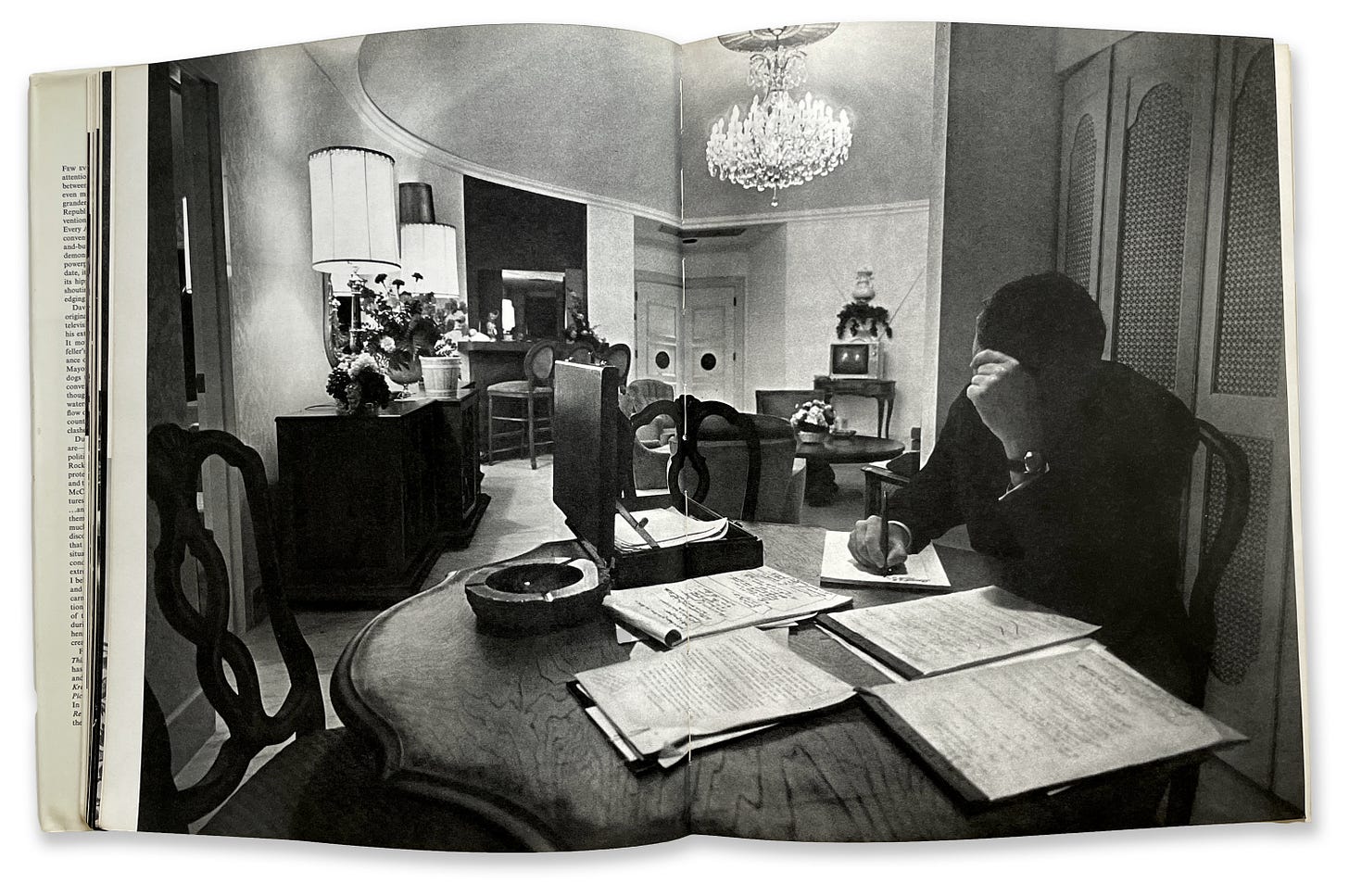

Access was critical in David Douglas Duncan’s coverage of the 1968 political conventions. Tapped by NBC News president Reuven Frank to produce nightly televised segments, Duncan narrated his “photo essays of the air,”3 bringing his perspective as a war photographer fresh off the battlefield in Vietnam, to the nation's living rooms.

Duncan’s photos were immortalized in his book, Self-Portrait: U.S.A. Very few of images from the book exist online, which is a shame. This rare, quiet photo of Richard Nixon—alone, unguarded—writing his acceptance speech in his hotel room wouldn’t happen today.

“I shot my pictures as I found them, rooting for no one, favoring nobody, thrilled with much of what I found, reflective because of new responses discovered within myself and grateful to this experience that released them,” Duncan wrote. Love that.

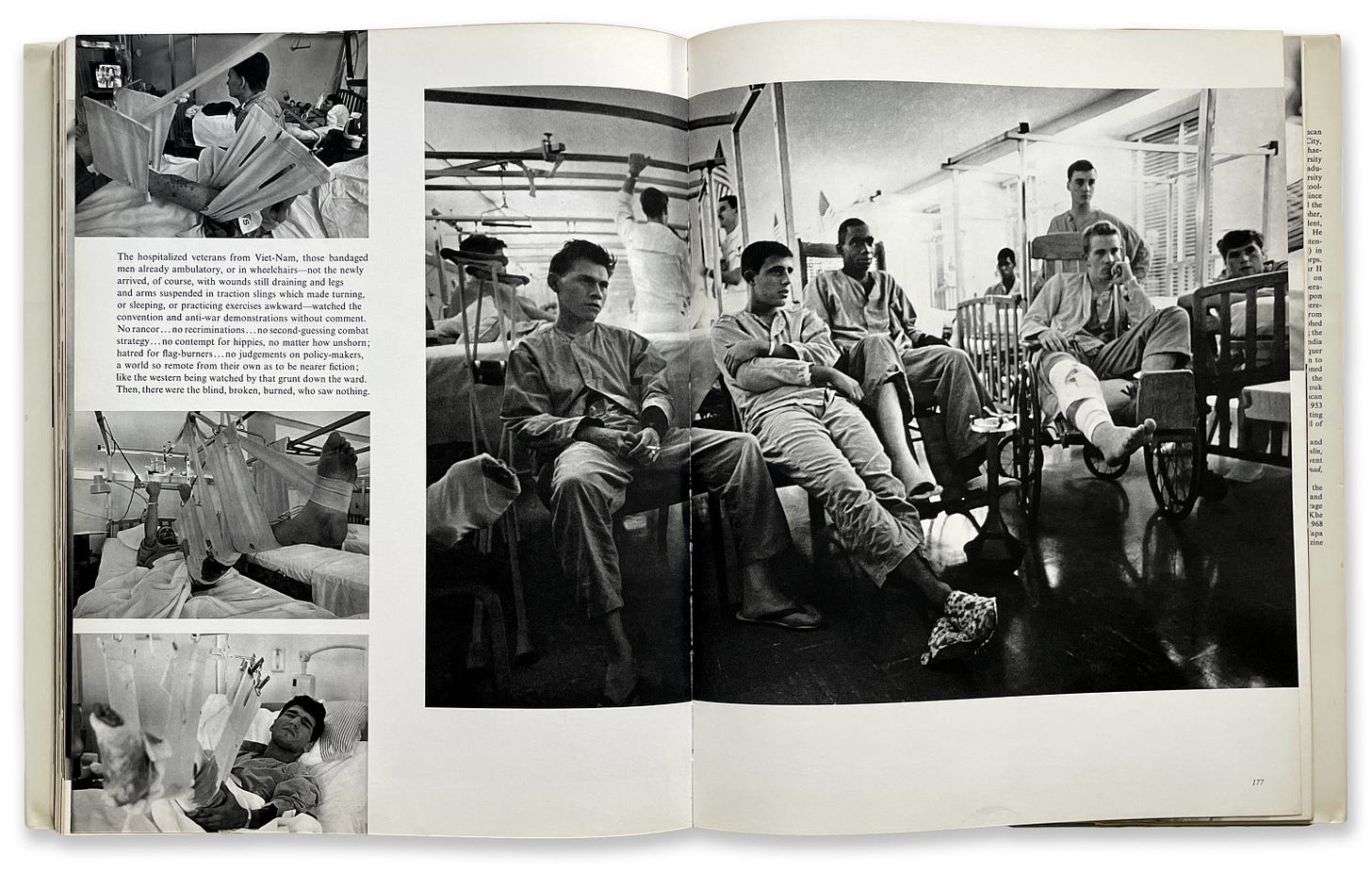

But what I believe makes Self-Portrait: U.S.A. brilliant are the unexpected photos, like these of wounded soldiers listening to the DNC at the nearby Great Lakes Naval Hospital.

Side note: I met David Douglas Duncan once, in 2010 at Visa pour l'image in France. I was star struck, introduced myself, then he slapped me in the face. Hard. I deserved it—I’d published one of his photos from the Korean War in TIME and promised to send him a copy. I forgot. He didn’t. Lesson learned.

Back to politics…

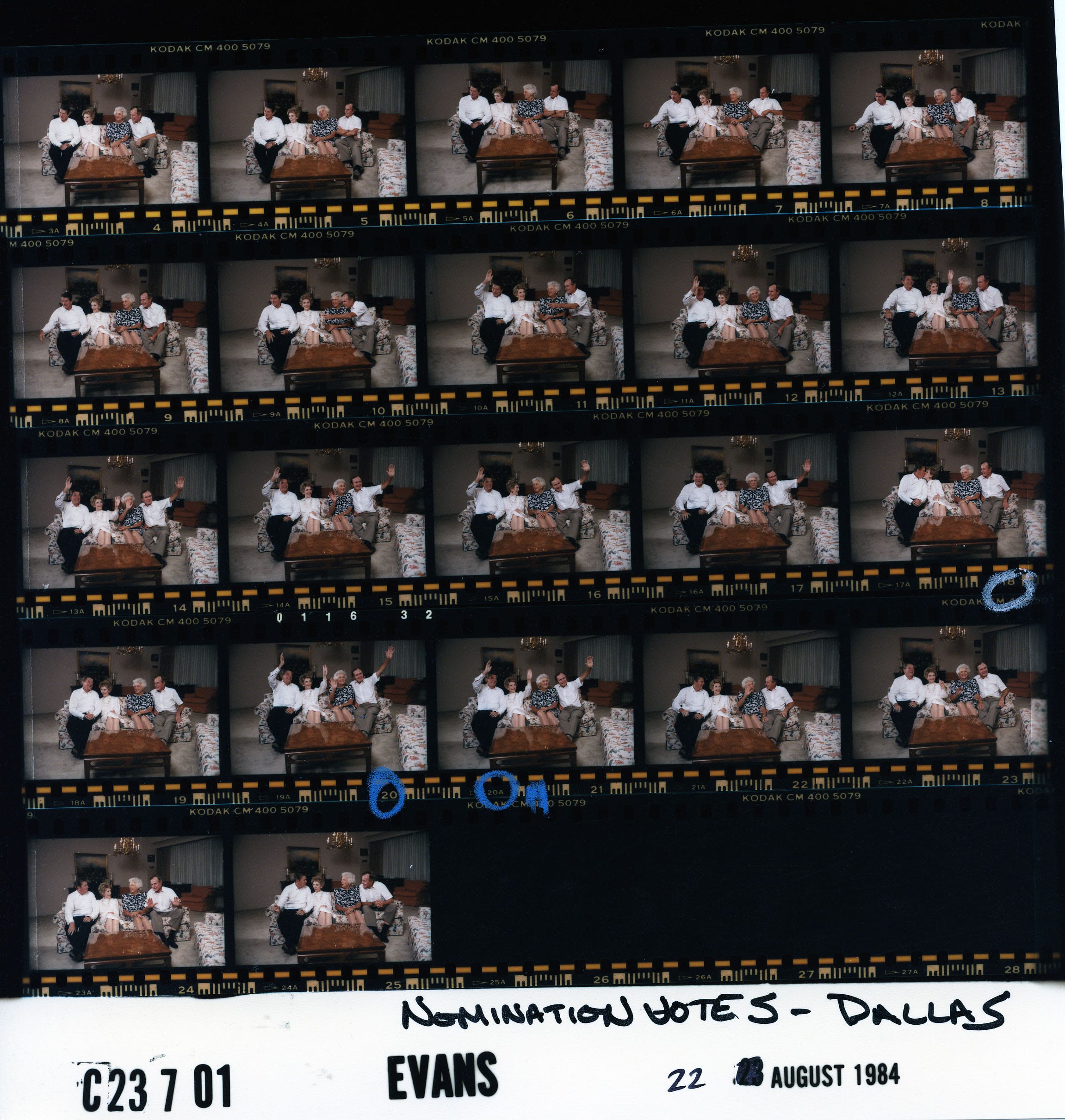

Then there’s perceived access. You’d think New York Times photographer George Tames is alone in the hotel room with the Reagans and the Bushes at the 1984 Republican National Convention, documenting a private, unscripted moment.

It’s an illusion. The photo sells access, but in reality, it’s carefully managed—there were several other photographers in the room, including two from the White House: Michael Evans, kneeling, left of Thames...

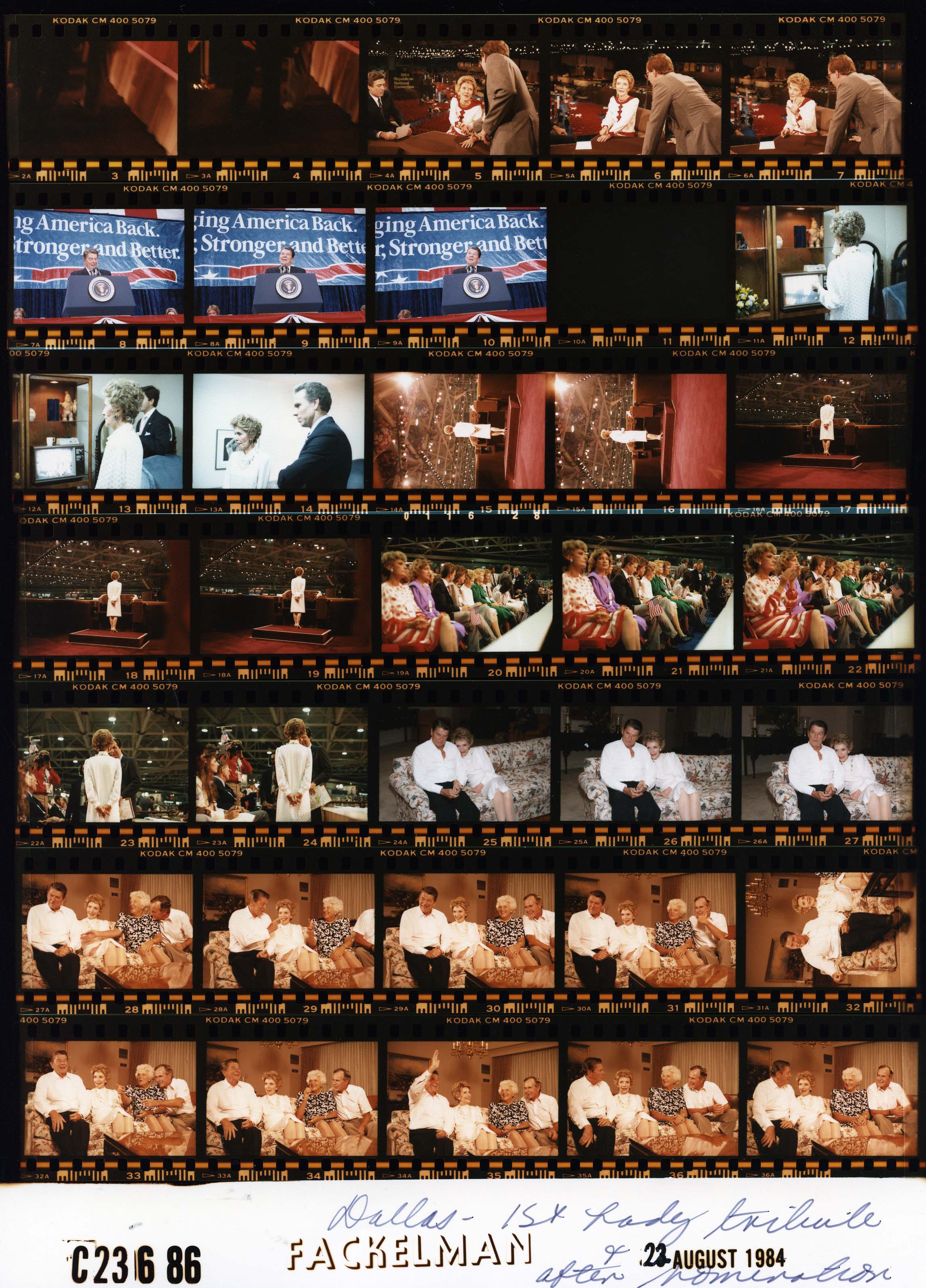

And Mary Anne Fackelman, who was trailing Nancy Reagan that day and wound up on the hotel room couch too.

Fackelman’s contact sheet is a gold mine—check out frames 17 (Christopher Morris vibes), 25, and 33 (a near-moment of Tames). Fackelman was the first woman hired as a White House photographer and had access others could only dream of.

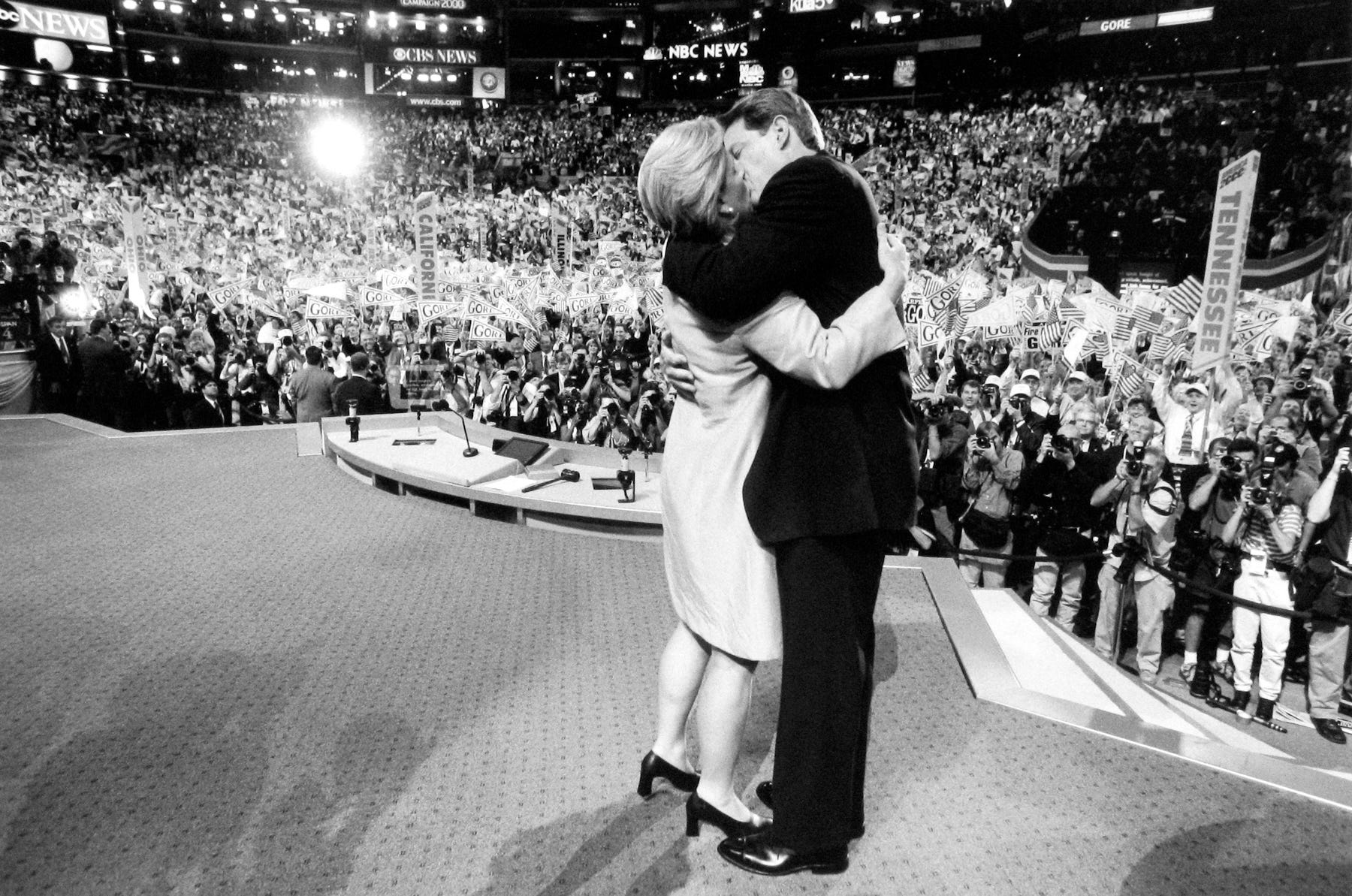

Once again, the illusion of intimacy and exclusivity. TIME’s Diana Walker wasn’t the only photographer on the stage, but her angle captures a not-so-fleeting moment that feels intimate—perfectly crafted for TV.

I went down the rabbit hole of convention photos, trying to decipher what, if anything, is real. This touching photo by Pete Souza of President Obama with his daughters backstage at the 2012 DNC? Real.

But Souza was Obama’s photographer—does it still count? Well, knowing Souza, absolutely. Though I’m sure plenty of other photographers would’ve killed for that kind of access. But if the room had been full of cameras, would the moment still have felt so unguarded? No.

Callie Shell, one of the true GOATs of political photography, was all alone with Hillary Clinton backstage at the 2016 DNC, watching her daughter introduce her on the night she accepted the nomination for president.

“The former secretary of state appeared tense, but not nervous,” Shell wrote, on assignment for CNN—not TIME.

Moments alone with the candidates like this didn’t happen at this year’s conventions. Gone is the intimacy. Aesthetics have taken over.

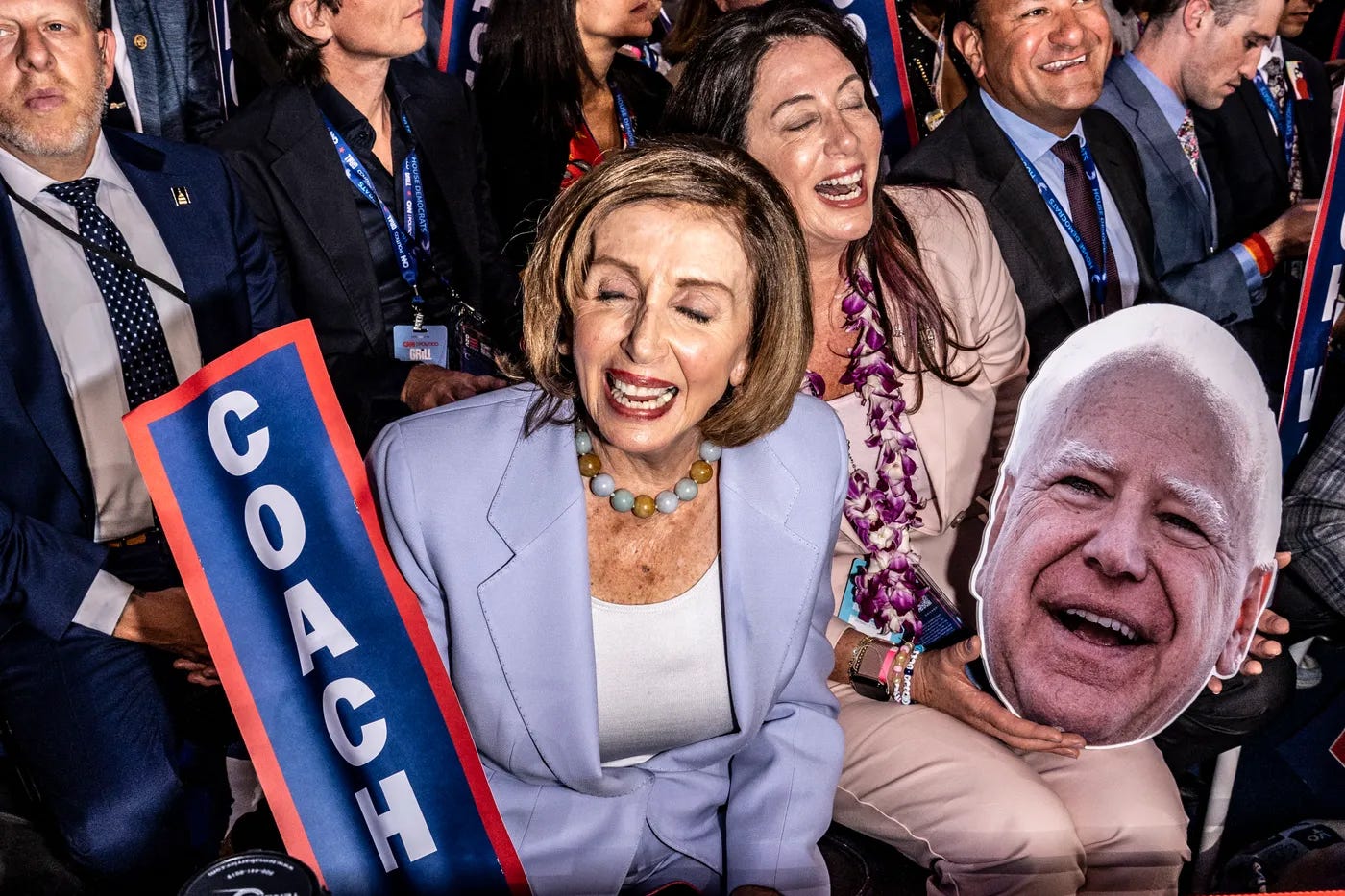

Henri Cartier-Bresson once said that using a flash was “monstrous” and “impolite, like coming to a concert with a pistol in your hand.” Some of the photos from the 2024 conventions were definitely monstrous.

Mark Peterson has been temporarily blinding politicians with his strobe for years. “The flash is like crack to them,” he once said.

A regular contributor to The New York Times Opinion section (mostly b&w) and New York magazine (mostly color), Peterson’s flash does more than light the scene—it defines it. It’s his signature look, one he’s refined and mastered. And it’s contagious.

Sinna Nasseri came to the RNC, as Cartier-Bresson might say, with “a pistol in hand” and made many of my favorite images from the convention for The New Yorker. That shadow? It’s no mistake.

A more ominous mood was captured by Joseph Rushmore for The Atlantic. Trump looming behind the blown-out balloon and boys is deliberate, suggesting a lot more than just a fleeting moment on stage.

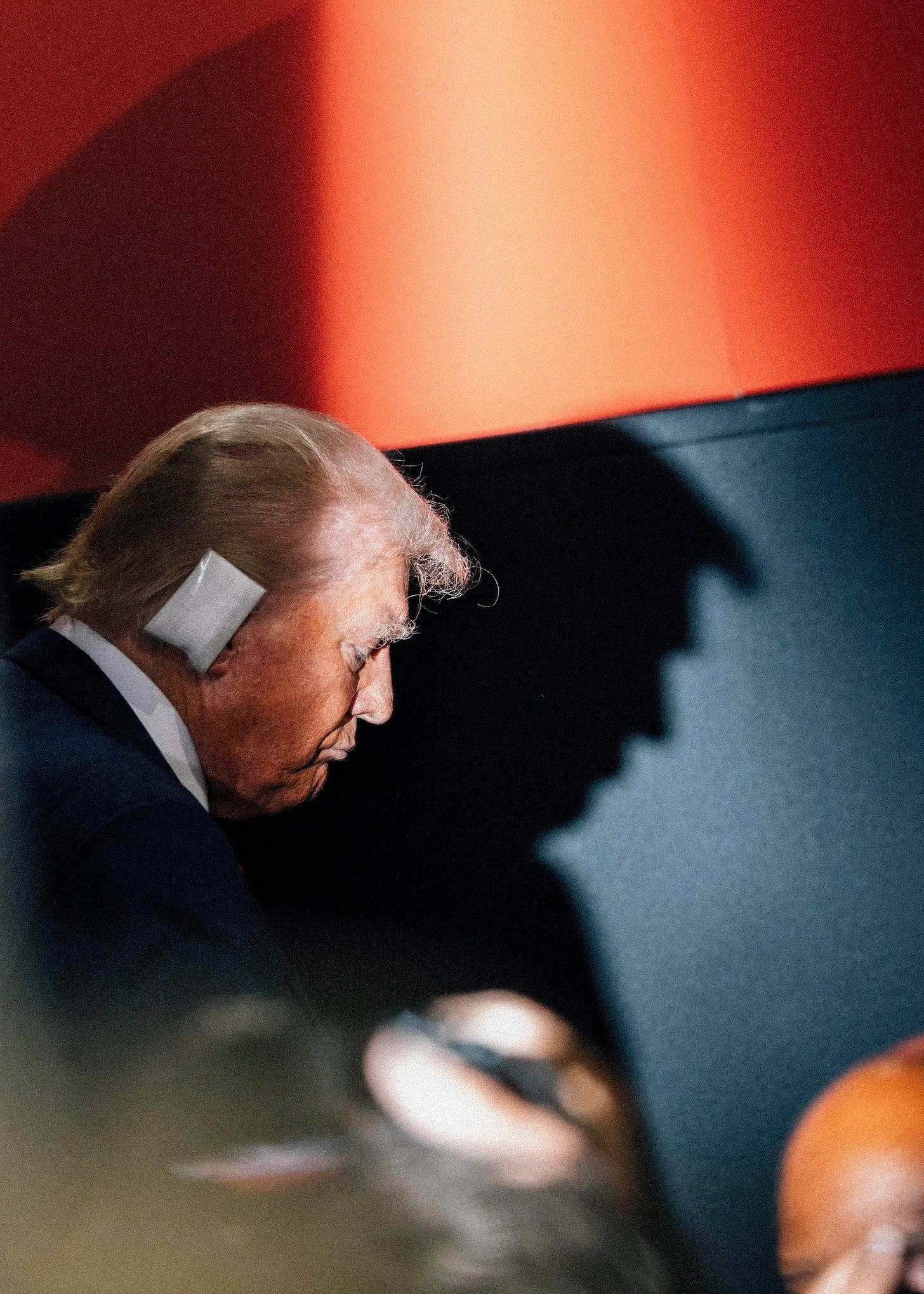

There were glimmers of access at the RNC, like this backstage grab by New York Times photographer Doug Mills. The splashes of Republican red across the frame are striking and of course Trump’s bandage…

Mills captured this moment just five days after photographing the assassination attempt on Trump in Pennsylvania. Access like this is rarely given to photographers who are parachuting in for the day.

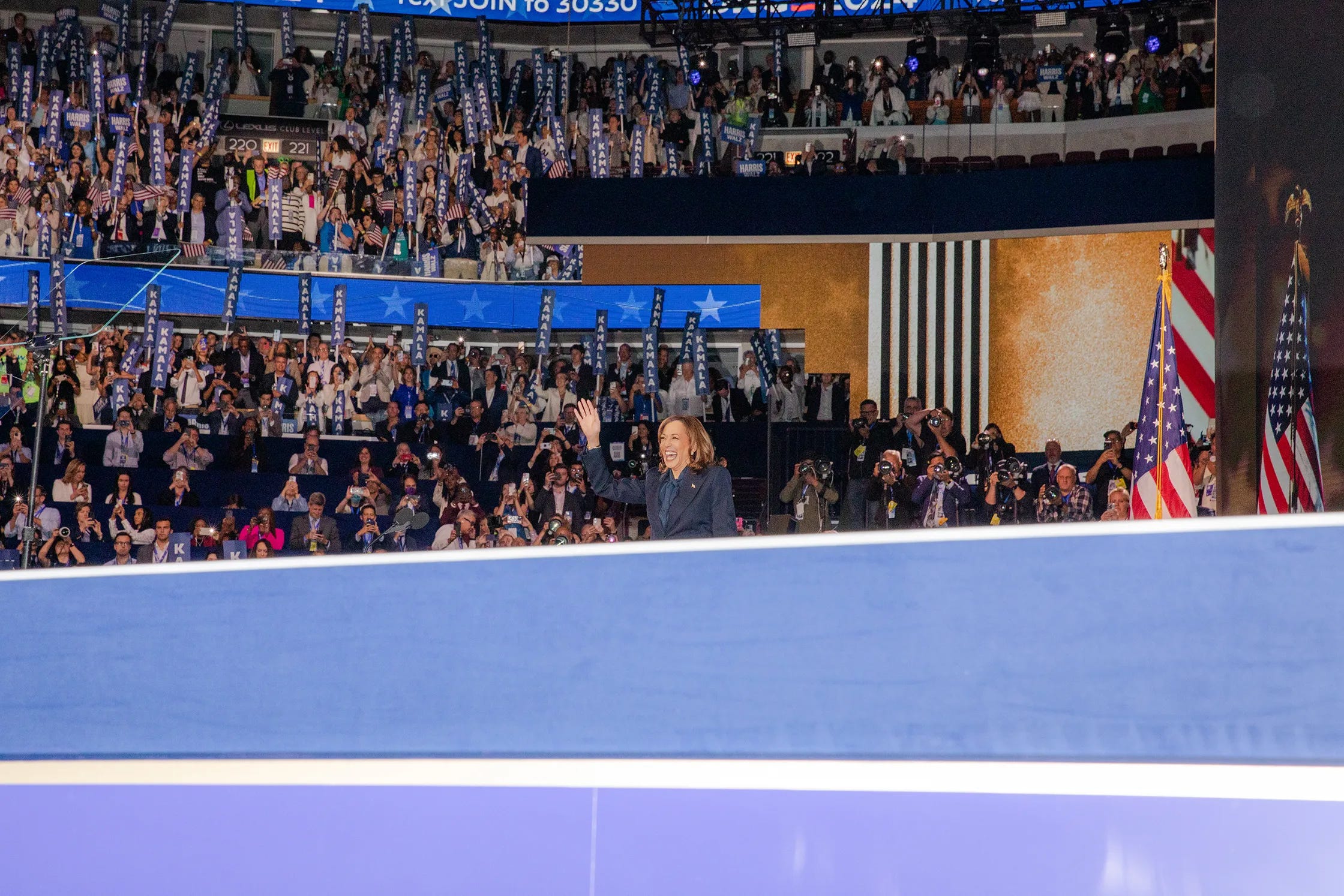

Did this kind of intimate moment happen backstage at the DNC? Surely, but was anyone there to photograph it? No. I’ve heard from multiple photographers that access at the DNC was the tightest it’s ever been. Soon after the convention, the White House News Photographers Association sent a letter to Vice President Harris’s team, accusing her campaign of “an unprecedented reduction in access.”

Gone are the moments.

Natalie Keyssar, photographing the DNC for The New Yorker, seemingly embraced the lack of access and overall artificiality of the convention, producing a set of images that the magazine described as “ambiguous, confusing.” I’d call them detached, even cynical.

“I’m leaning into looser and more imperfect images than usual, because the product that I’m shooting is so glossy,” Keyssar told The New Yorker. “I’m trying to throw some aesthetic sense of questioning into that experience, to be a glitch between the viewer and the show.” The product, the show…ok.

Garry Winogrand would often tell students, “Every photograph is a battle of form versus content. The good ones are on the border of failure.”

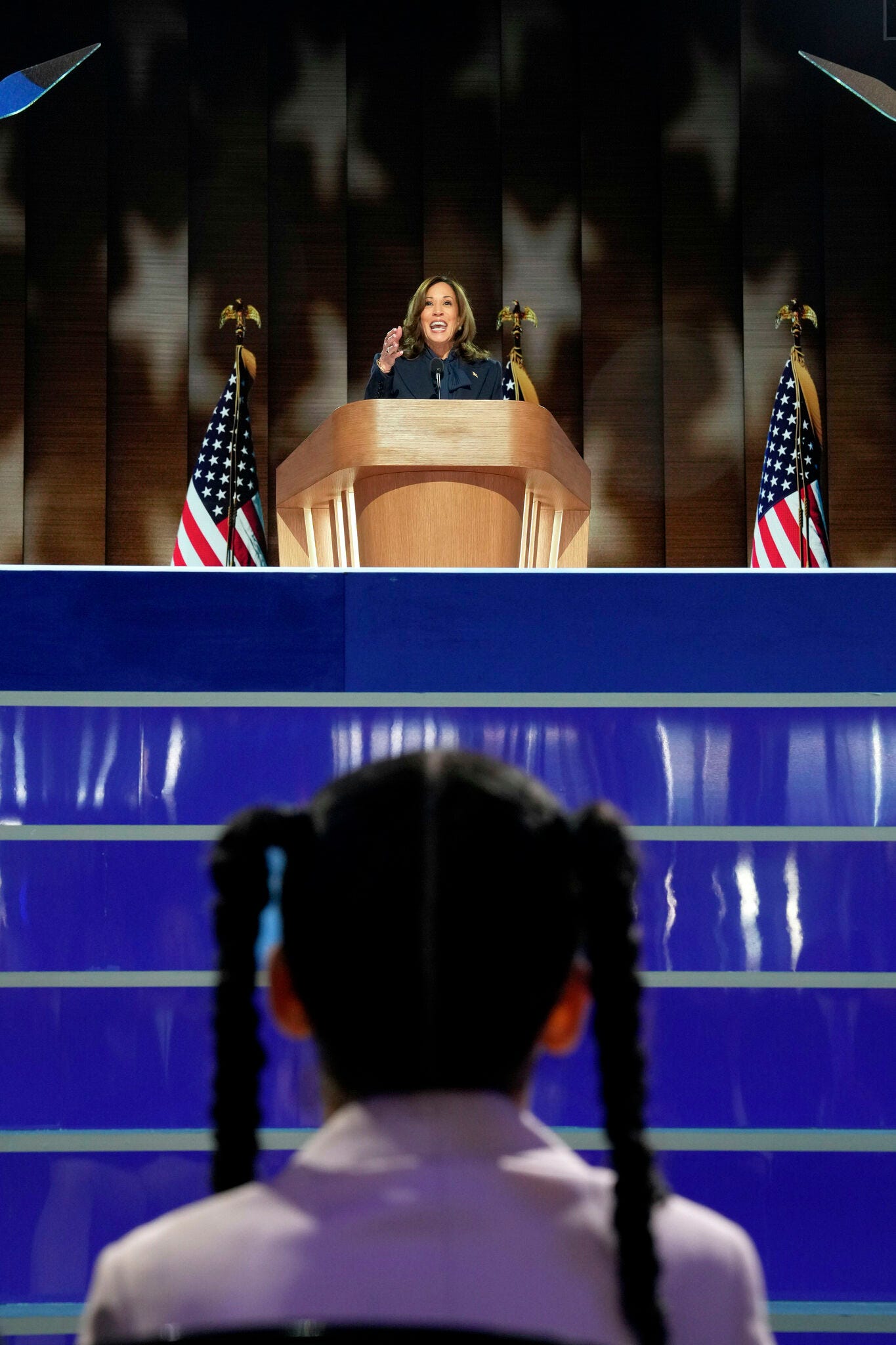

Alas, the most powerful and lasting photo from the DNC wasn’t made backstage with insider access or by an official White House photographer. It was taken from the crowd, directly in front of Vice President Harris during her acceptance speech. Access be damned, New York Times photographer Todd Heisler nailed it.

I see echoes of Winogrand’s Kennedy photo in Heisler’s image: where the symbolic television stood, Harris’s niece takes center stage. It’s symbolic, an instant classic—a singular moment that transcends the “product” and outshines the “show.”

The opposite of cynical, far from monstrous. Pretty perfect.

Julie Bosman, “Behind the Scenes of Power,” The New York Times, April 19, 2012.

John Loengard, Life Photographers: What They Saw (New York: Bulfinch Press, 1998), 345.

David Douglas Duncan, Self-Portrait: U.S.A. (New York: Harry N. Abrams, Inc., 1969), 1.

Patrick, you present these themed essays with great authority and footnoted like a true academic! A great read. Every time I finish one one of your entries, I go back and look to see if there is one I missed! Very nice!

Love this and everything about Field of View. Made me remember an election night back in 2010 … going to post to IG and tag you. Thank you for what you do.