The Most Meaningful Photo in Olympic History

It's not the viral surfing photo.

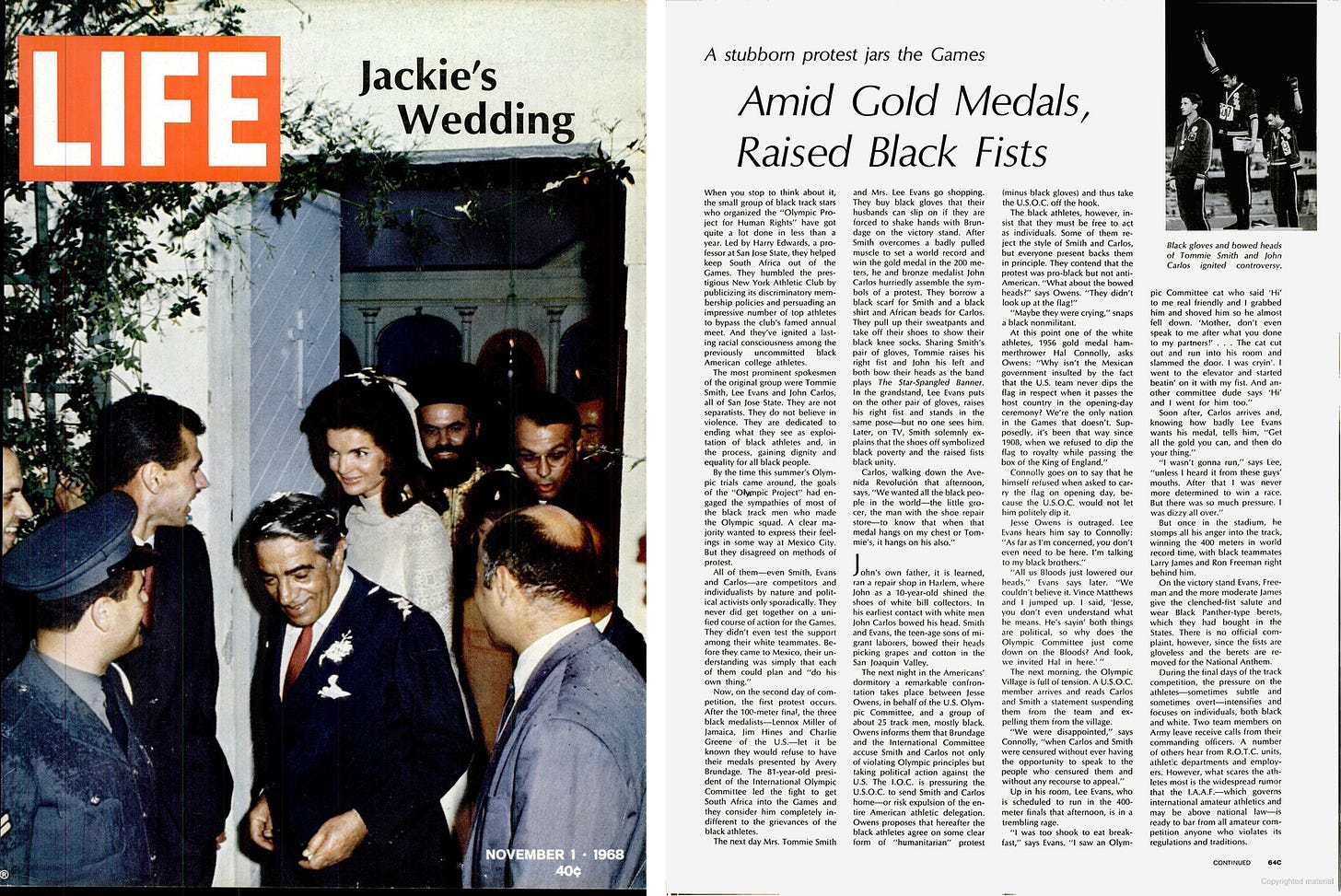

Medal ceremonies are the grip-and-grins of the Olympics—orchestrated, bite-the-medal photo ops that rarely transcend into something meaningful and enduring. So much so, LIFE magazine photographer John Dominis didn’t realize the importance of what he’d captured on October 16, 1968, at the Olympics in Mexico City.

“I was expecting a normal ceremony,” Dominis said in an interview with David Davis in 2008. “I hardly noticed what was happening when I was shooting.”

As the Star-Spangled Banner rang throughout the stadium, 200-meter gold medal winner Tommie Smith and bronze medalist John Carlos bowed their heads and raised their black-gloved fists to protest racial injustice in the United States. The crowd went silent. Dominis, perfectly positioned about 20 feet away, squeezed the shutter.

“For a few seconds, you honestly could have heard a frog piss on cotton,” Carlos, the bronze medalist, later wrote. “There’s something awful about hearing fifty thousand people go silent, like being in the eye of a hurricane.”1

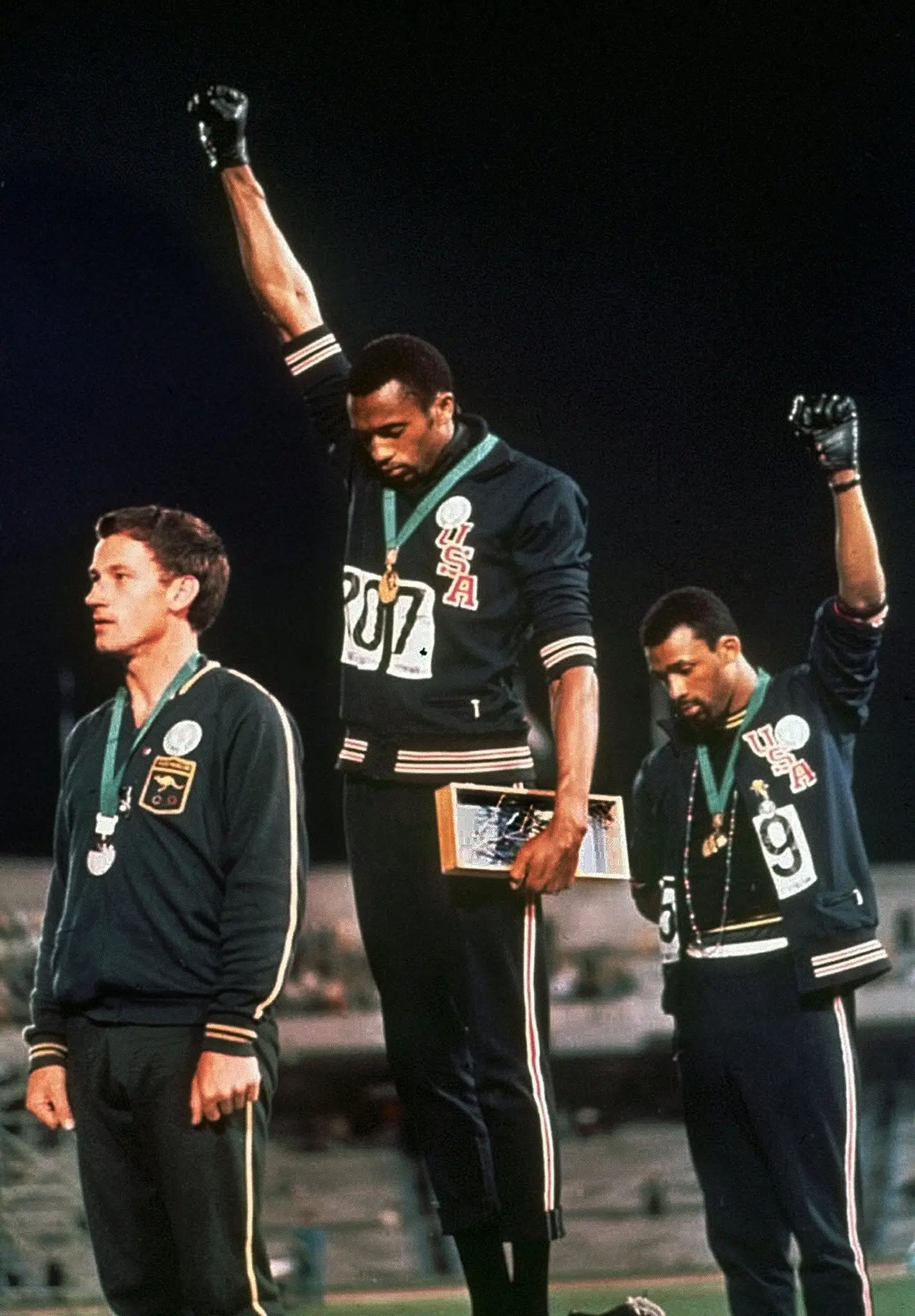

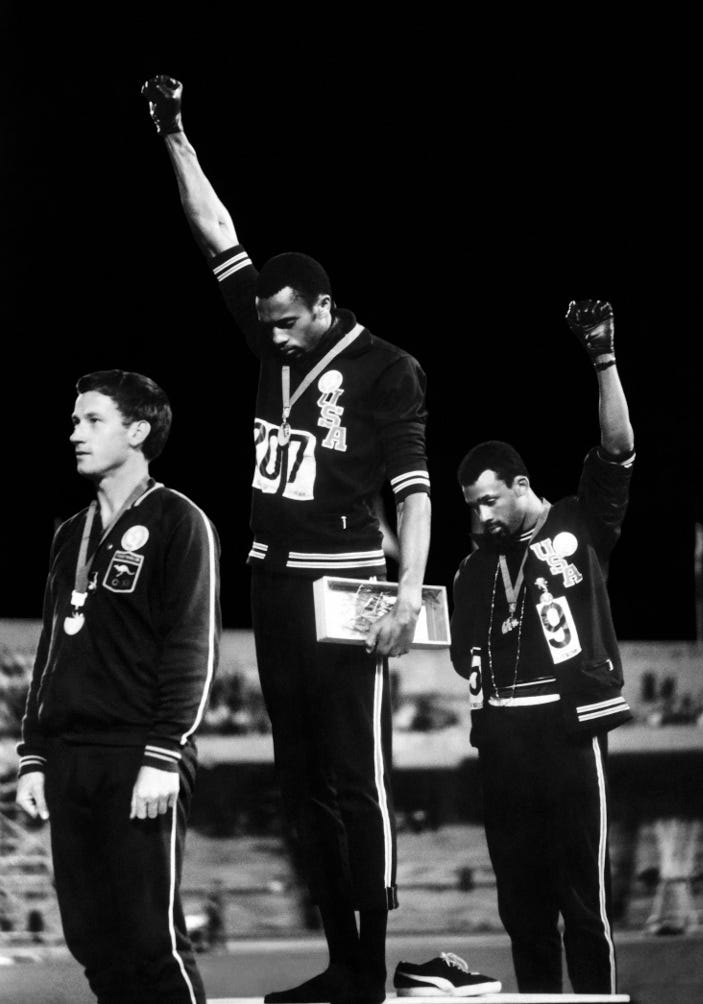

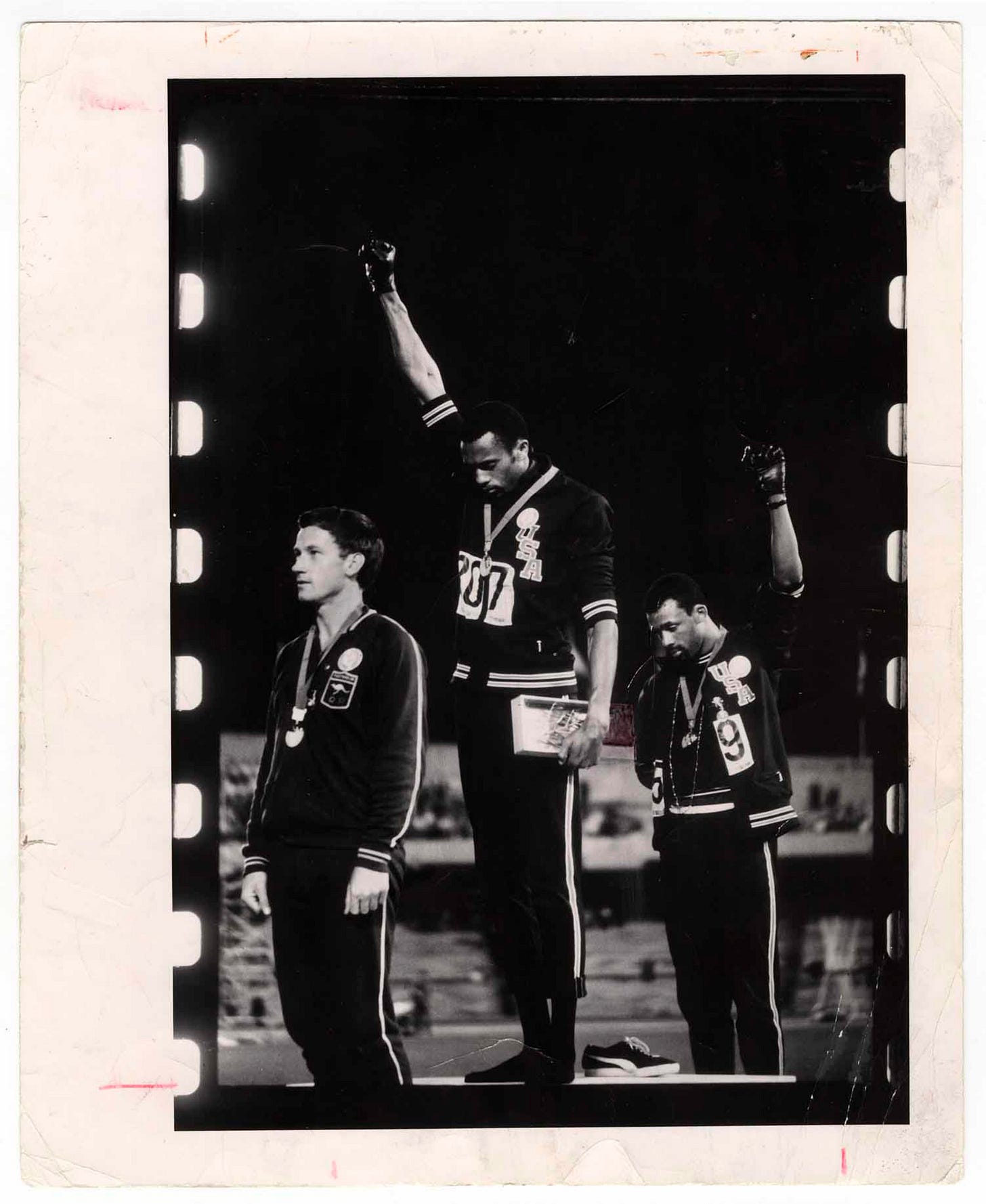

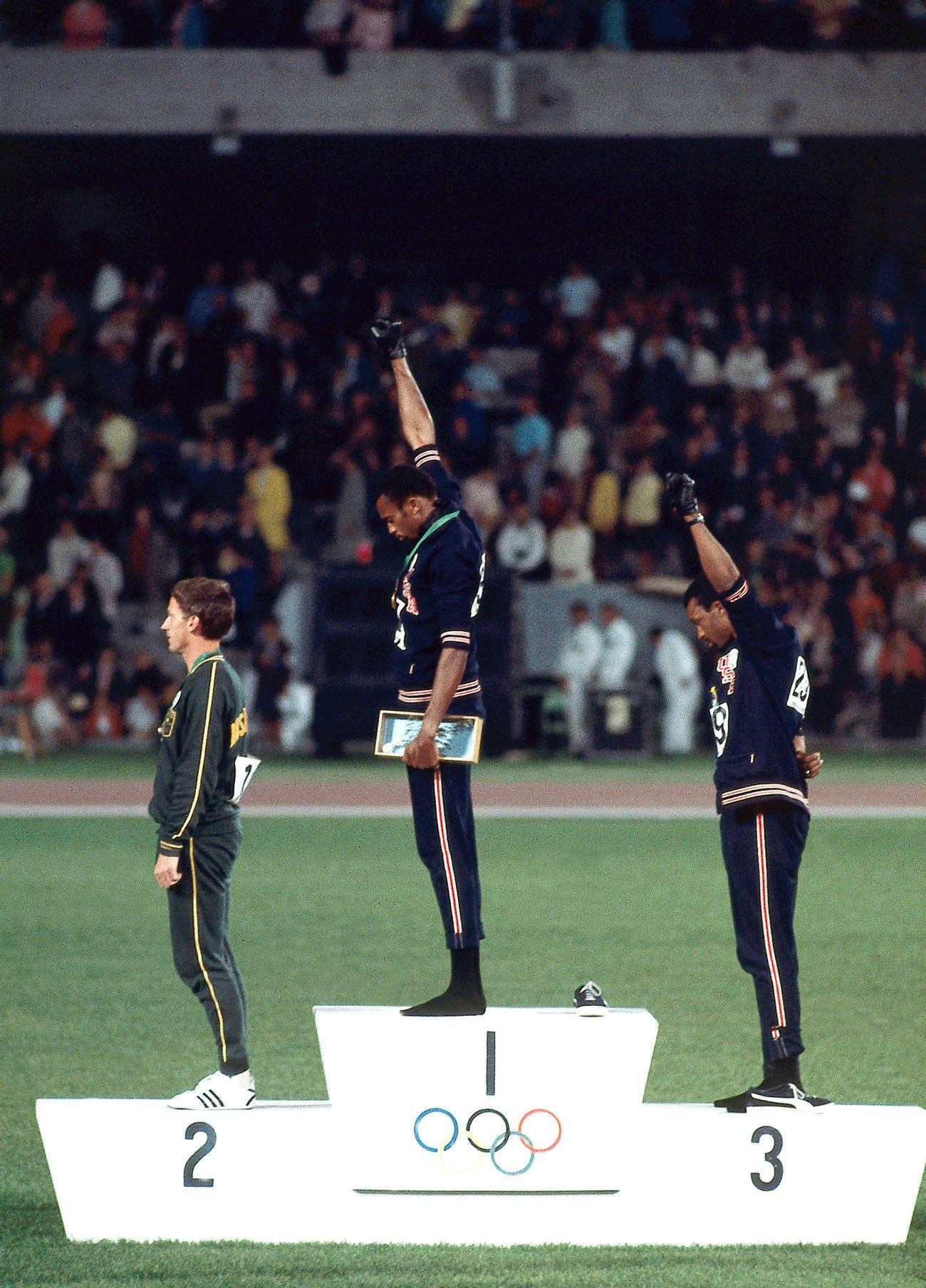

There are two nearly identical versions of Dominis’s unforgettable photo—one in color and one in black and white.

Dominis’s photo isn’t a quick read—the details are immense, profound. Smith and Carlos shared a single pair of black gloves, that’s why they’re only wearing one on each hand. Smith’s black socks and single black Puma rest on the medal platform, symbolizing poverty. Carlos’ unzipped jacket and beads around his neck symbolize the history of lynchings in the United States.

Australian silver medalist Peter Norman joined the protest by wearing a matching “Olympic Project for Human Rights” button. And the box Smith is holding contains an olive branch, symbolizing peace.

LIFE, not realizing the significance of Dominis’s photo, buried it in the November 1, 1968, issue.

Take note of the box with the olive branch—in some versions of Dominis’s photo, it’s been partially removed. The New York Times published this altered version in 2014, 2017, and 2021, as have others, including LIFE.

The International Center of Photography has a print of Dominis’s image in their archives that more clearly reveals the sloppy SpotTone job.

Unfortunately, Dominis is rarely credited for his color photo. The image was widely distributed by the Associated Press and lives in their archive without attribution, likely because Dominis was shooting for the International Olympic Photo Pool (IOPP), which meant his images became part of the collective “pool.” It’s a shame—Dominis’s name should live on alongside his iconic photo.

Another detail: I’d always assumed that Dominis had inadvertently cropped out Smith’s black-socked feet and Puma in the color version. Until I came across this glorious full-frame print, recently auctioned for $10,065.

Here are all the variations, including the doctored black and white print. They’re nearly identical, but pay close attention to Norman’s left hand and the disappearing olive branch box to spot the differences.

Regardless of which version is seen, Black Power Salute will continue to resonate and inspire. There are at least five documentaries and two statues (at the National Museum of African American History and Culture and San Jose State University) honoring the moment.

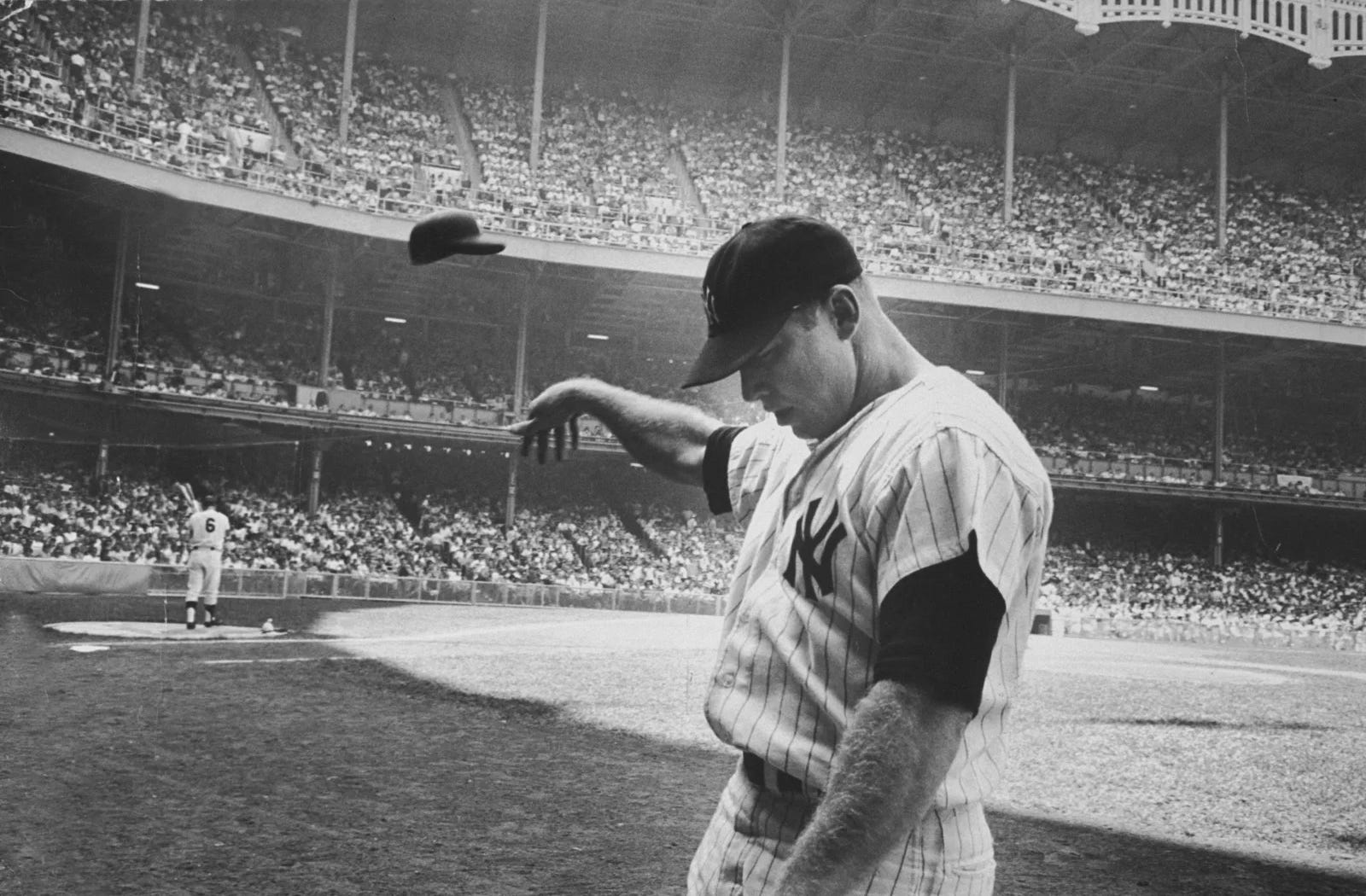

Side note: Dominis also shot one of my all-time favorite baseball images—this telling photo of Mickey Mantle near the end of his career in 1965. The antithesis to the celebratory bat flip.

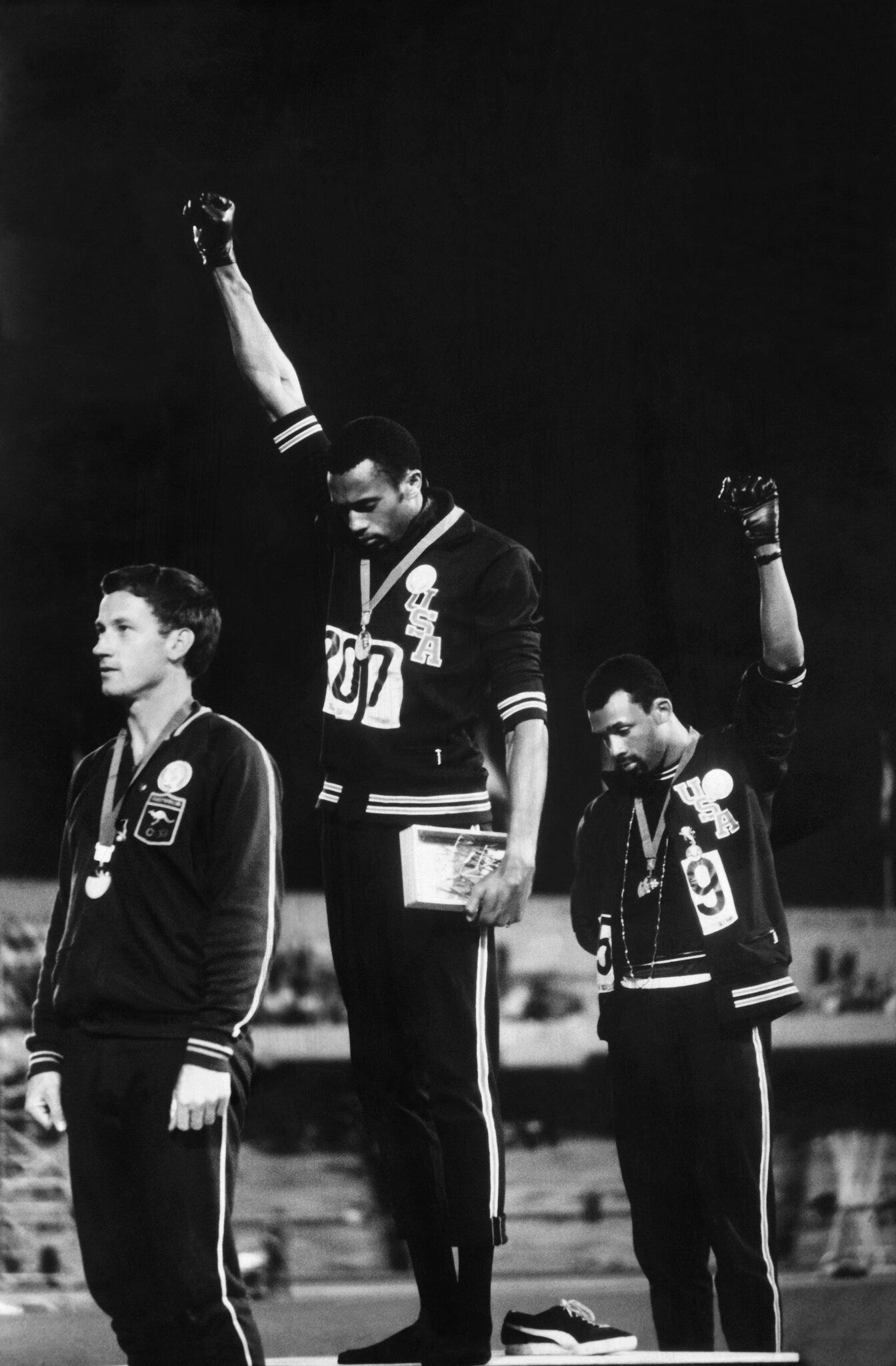

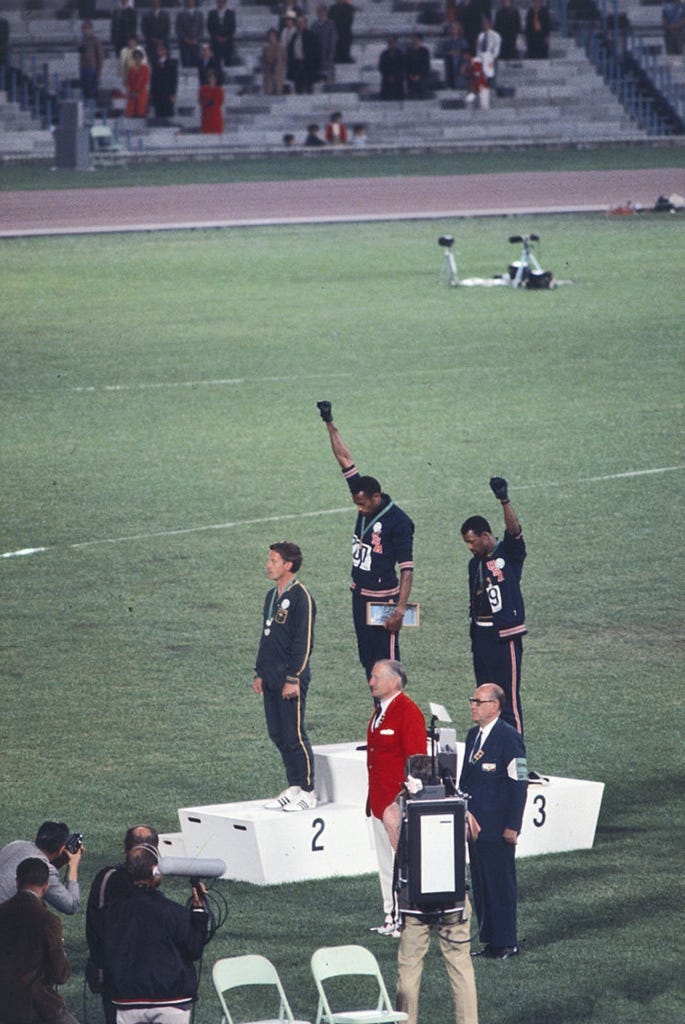

As expected, several other photographers were inside Estadio Olímpico Universitario that evening in 1968, most notably sports photography legend Neil Leifer. Of course, he nailed it.

Leifer’s straight-on position, far to the right of Dominis, emphasizes Smith’s black socks and lone Puma. Look closely, Smith’s eyes are closed—powerful.

Italian photographer Angelo Cozzi shot from an elevated position, isolating the athletes against the empty green infield. Dominis is in the scrum of photographers in the lower right.

UPI moved a brutally-cropped version of Cozzi’s photo, which continues to make the rounds today, but it lacks a crucial detail: Smith’s and Carlos’s shoeless, black-socked feet.

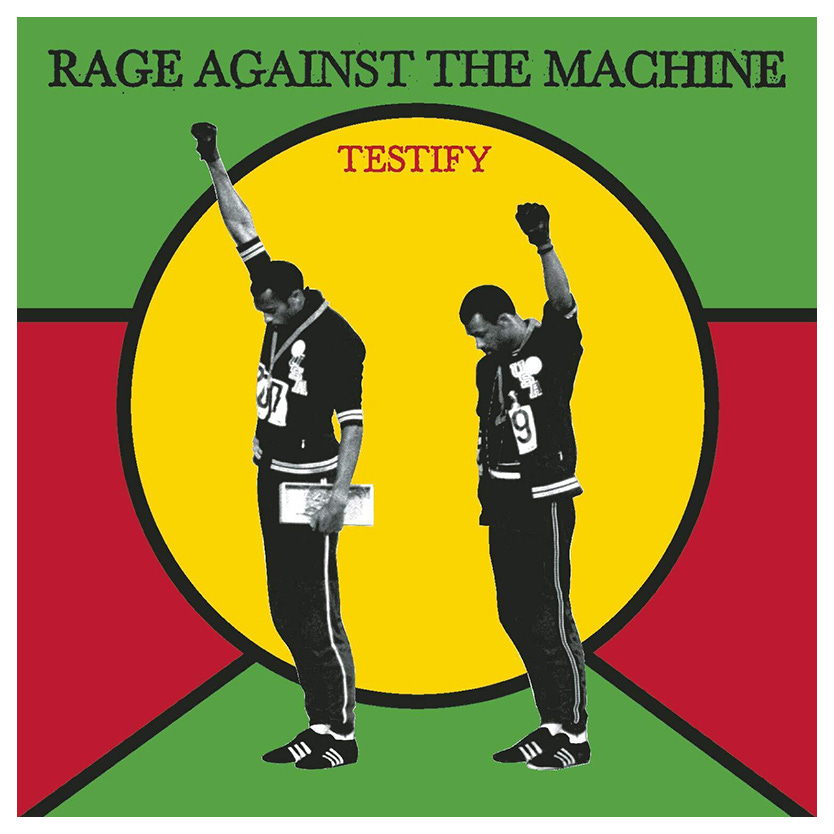

That missing detail didn’t stop Rage Against the Machine from hijacking Cozzi’s image for the cover of their 2000 single, Testify. Whoever designed the cover crudely drew in some Adidas—not Pumas.

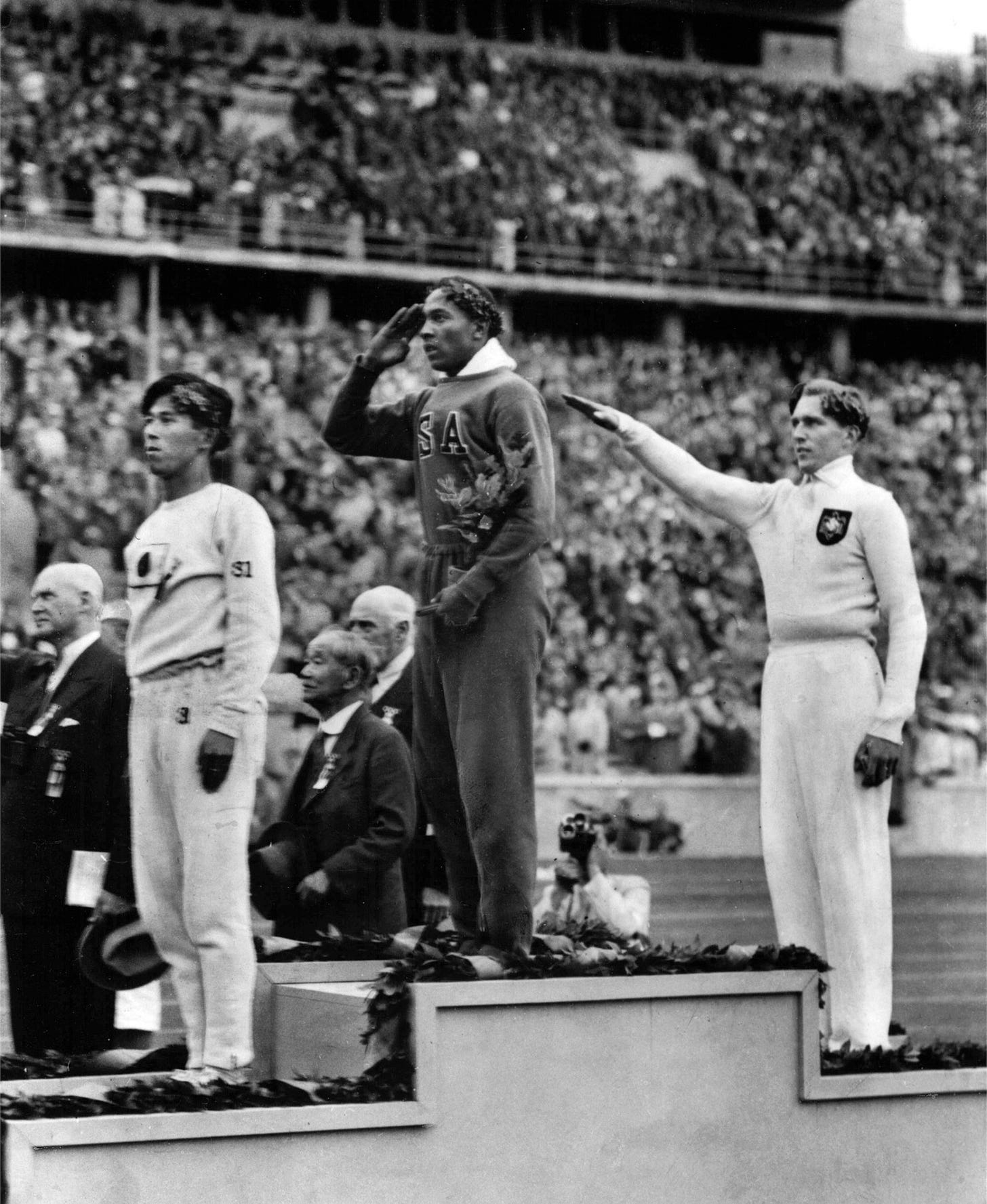

Another unforgettable medal ceremony happened during the 1936 Olympics in Berlin.

Anthony Camerano, photographing the games for the Associated Press, made this photo of Jesse Owens saluting the American flag on the medal stand after winning gold in the broad jump. Silver medalist Luz Long, who controversially befriended Owens during the Olympics, is giving the Nazi salute.

Owens’s performance was legendary—he won an unprecedented four gold medals in Berlin and broke three world records. Adolf Hitler, who was in attendance, was not pleased.

“When Owens finished competing, the African-American son of a sharecropper and the grandson of slaves had single-handedly crushed Hitler's myth of Aryan supremacy,” Larry Schwartz wrote in ESPN.

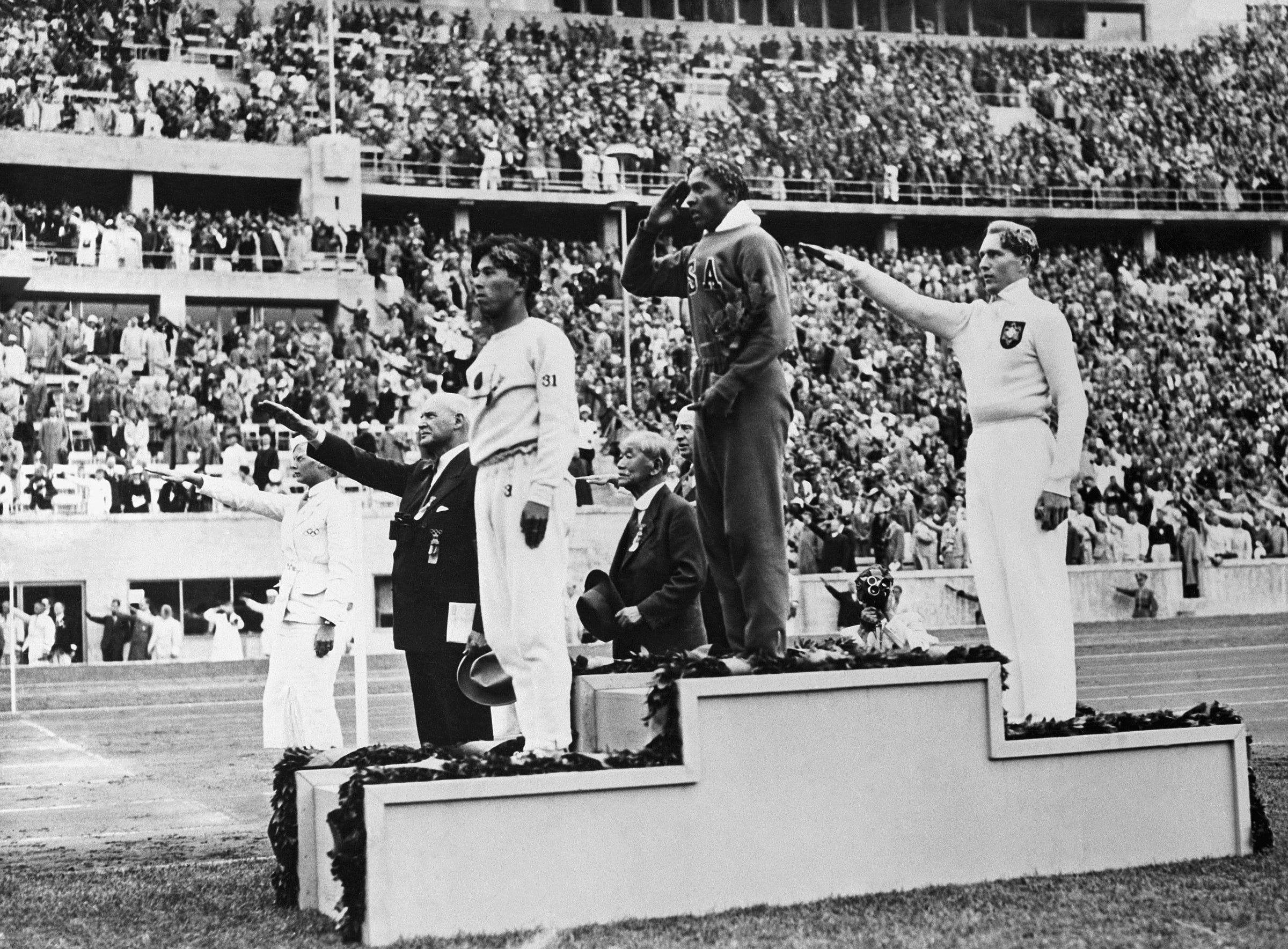

And then there’s this photo taken by Hitler’s personal photographer and close friend Heinrich Hoffman.

Hoffman’s shorter lens and greater depth of field paid off—Owens, centered in the frame holding an oak sapling and wearing an Olympic laurel wreath, appears lost in a sea of Nazi salutes. It’s haunting.

There are conflicting reports whether Hitler acknowledged Owens for his triumphant wins or not. “The Americans ought to be ashamed of themselves for letting their medals be won by Negroes.” Hitler reportedly said. “I myself would never even shake the hand of one.”2

Fast forward to the 2024 Olympic Games in Paris, and a strikingly different kind of medal ceremony photo emerged. Elsa Garrison captured this image of American gymnasts Simone Biles and Jordan Chiles celebrating Brazilian Rebeca Andrade, who won gold in floor exercise.

“To me this image embodies not only the Olympic spirit but what women’s gymnastics is all about—women supporting women,” Garrison wrote on Instagram. Coincidentally or not, Garrison is the first woman staff photographer for Getty Images.

Garrison’s photo hits a completely different tone from the previous two medal ceremonies—surprising, joyful—but echoes the deep relationships between the athletes.

Owens described the essence of that bond, one that transcends politics, beautifully after the Olympics. “Even if you melted down all my medals and trophies, they couldn’t make the 24-carat friendship I felt for Luz Long at that moment any more golden,” Owens said. “Hitler must have gone mad when we hugged.”

John Carlos, The John Carlos Story: The Sports Moment That Changed the World (Chicago: Haymarket Books, 2011), 121.

Baldur von Schirach, Ich Glaube an Hitler (Hamburg: Mosark, 1967), 217.

Great piece.

To add a bit more for those curious. Australian silver medalist Peter Norman's story, is a story in itself.

“As soon as he got home he was hated,” explains his nephew Matthew Norman, who has directed a new film – “Salute!” – about Peter’s life before and after the 1968 Olympics.

“A lot of people in America didn’t realize that Peter had a much bigger role to play. He was fifth (fastest) in the world, and his run is still a Commonwealth record today. And yet he didn’t go to Munich (1972 Olympics) because he played up. He would have won a gold.

“He suffered to the day he died.”

You can read more here

https://edition.cnn.com/2012/04/24/sport/olympics-norman-black-power/index.html

He was honoured with a statue at Albert Park in Melbourne in 2019.

Great analysis! I learned a lot. Thanks.