The Most Famous Mug Shot in History

A former President sits for a deceptively simple, yet profound, portrait. Like many before.

Rarely flattering, but utterly fascinating, mug shots are the most stripped-down form of portraiture. A mug shot can enrage. A mug shot can inspire. A mug shot can be a fundraising tool.

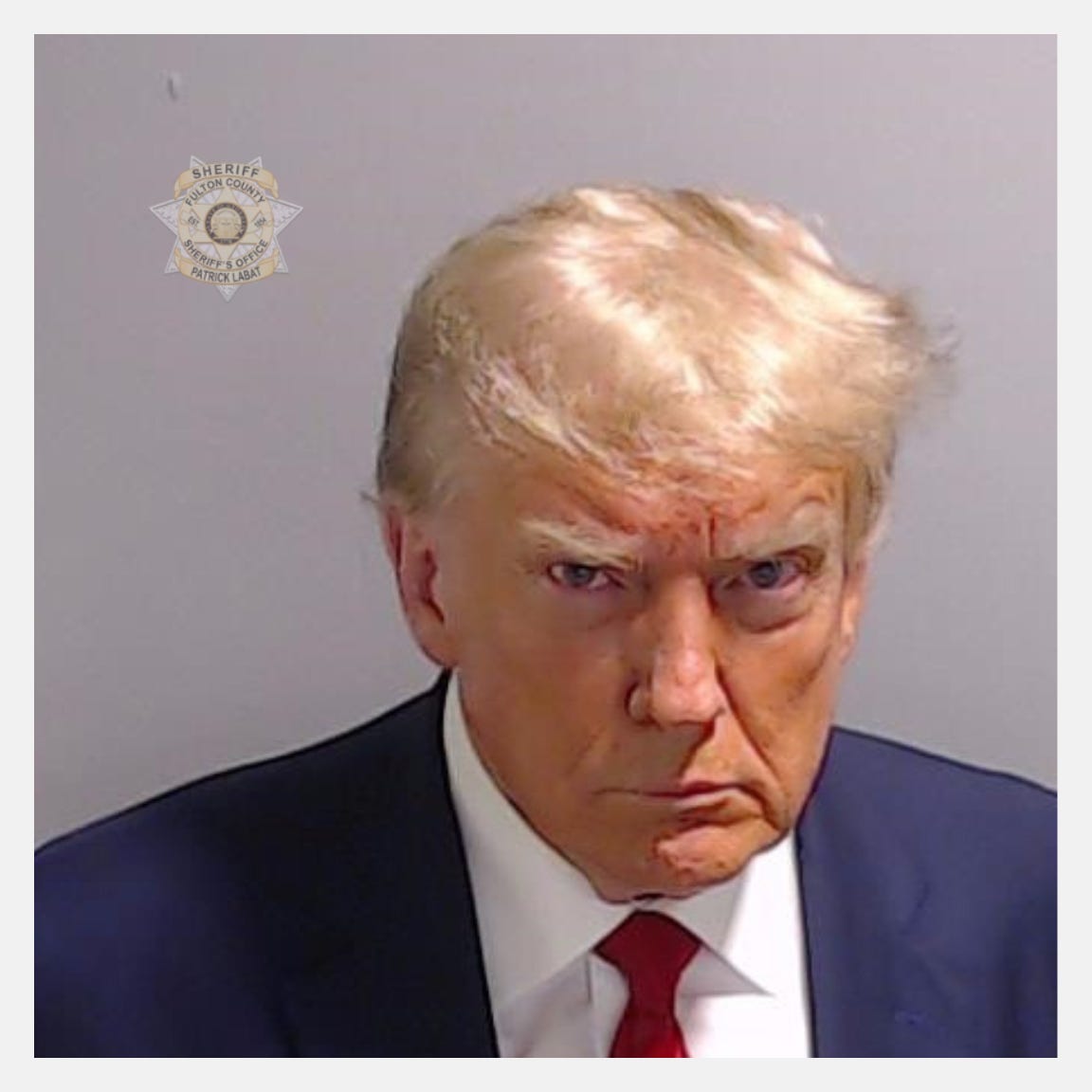

Alas, the internet finally got what it had been waiting for last week — a mug shot of former President Donald J. Trump.

The first appearance of the real Trump mug shot on X, aka Twitter, was posted simultaneously by @CFC_Weagle and @quebecween at 7:05 p.m. CST, August 24, 2023.

Curiously, this is a photo of the mug shot displayed on a screen — before the Fulton County Sheriff’s Office watermark was added. It must have been taken by someone inside the Sheriff’s office and spread from there.

The official version of Trump’s mug shot was released by the Fulton County Sheriff’s Office a few minutes later, this time with the watermark. CNN’s @kaitlancollins was one of the first to share the historic, unprecedented image, at 7:39 p.m CST.

Technically, the photo leaves much to be desired. Most likely shot with a webcam mounted atop an outdated, government-issued computer, the 1080 x 1080 px photo distributed by the Fulton County Sheriff’s Department bore the filename: DJT A.png.

Rightfully so, the Trump mug shot led almost every major newspaper. The Wall Street Journal played it yuge, 3 col. at the top. The Washington Post ran the photo smaller, under a bold 6 col. hed.

The Arizona Republic and The Atlanta Journal-Constitution went all-in, publishing the mug shot a full 6 columns wide, quality be damned.

The New York Times chose a more subtle route, and the Los Angeles Times skipped the mug shot altogether. What were they thinking?

But the best treatment of the mug shot heard round the world, without a doubt, was by the New York Post. I guarantee you they were sitting on dozens of quippy, ruthless headlines and instead, went with none. Brilliant.

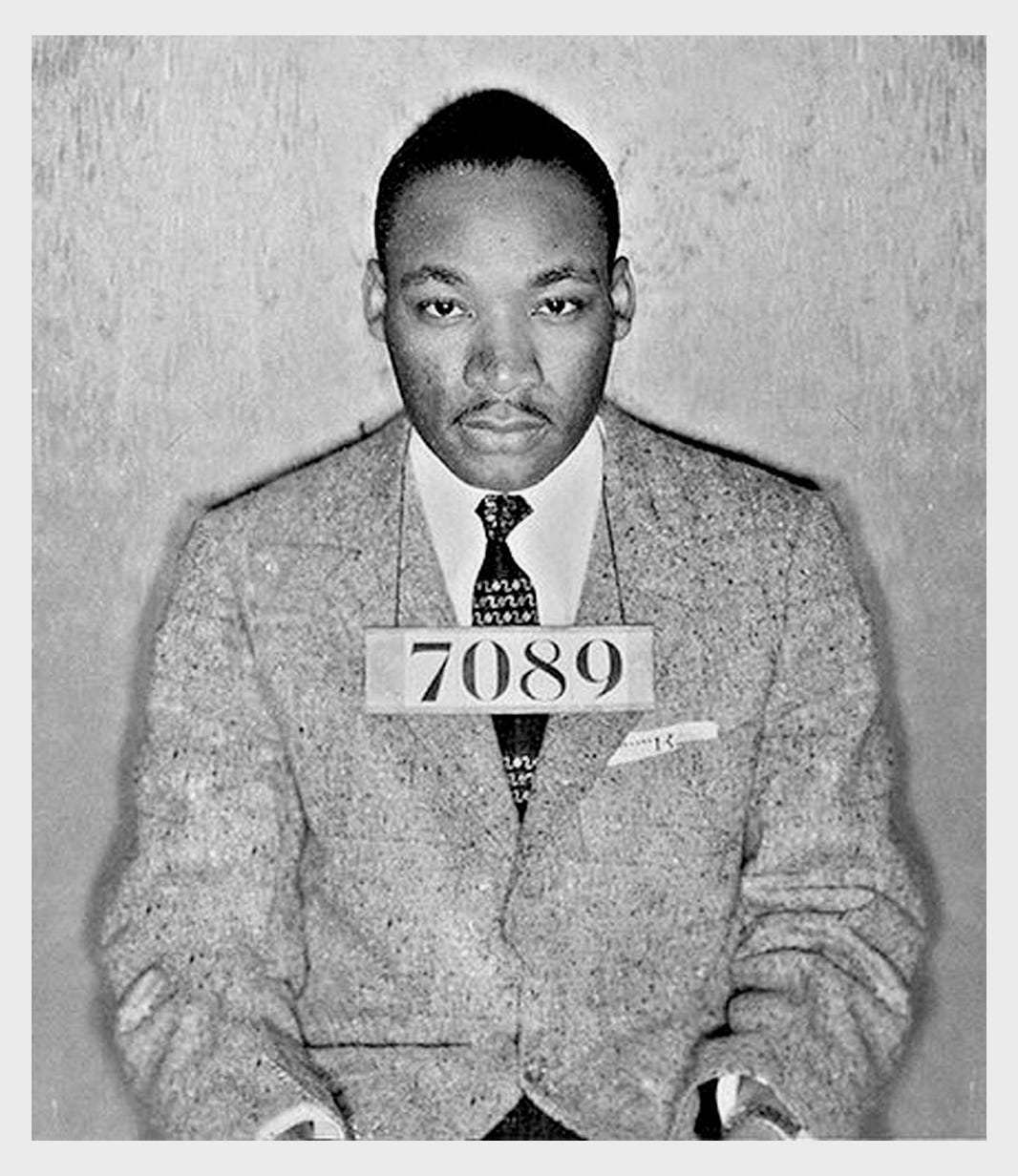

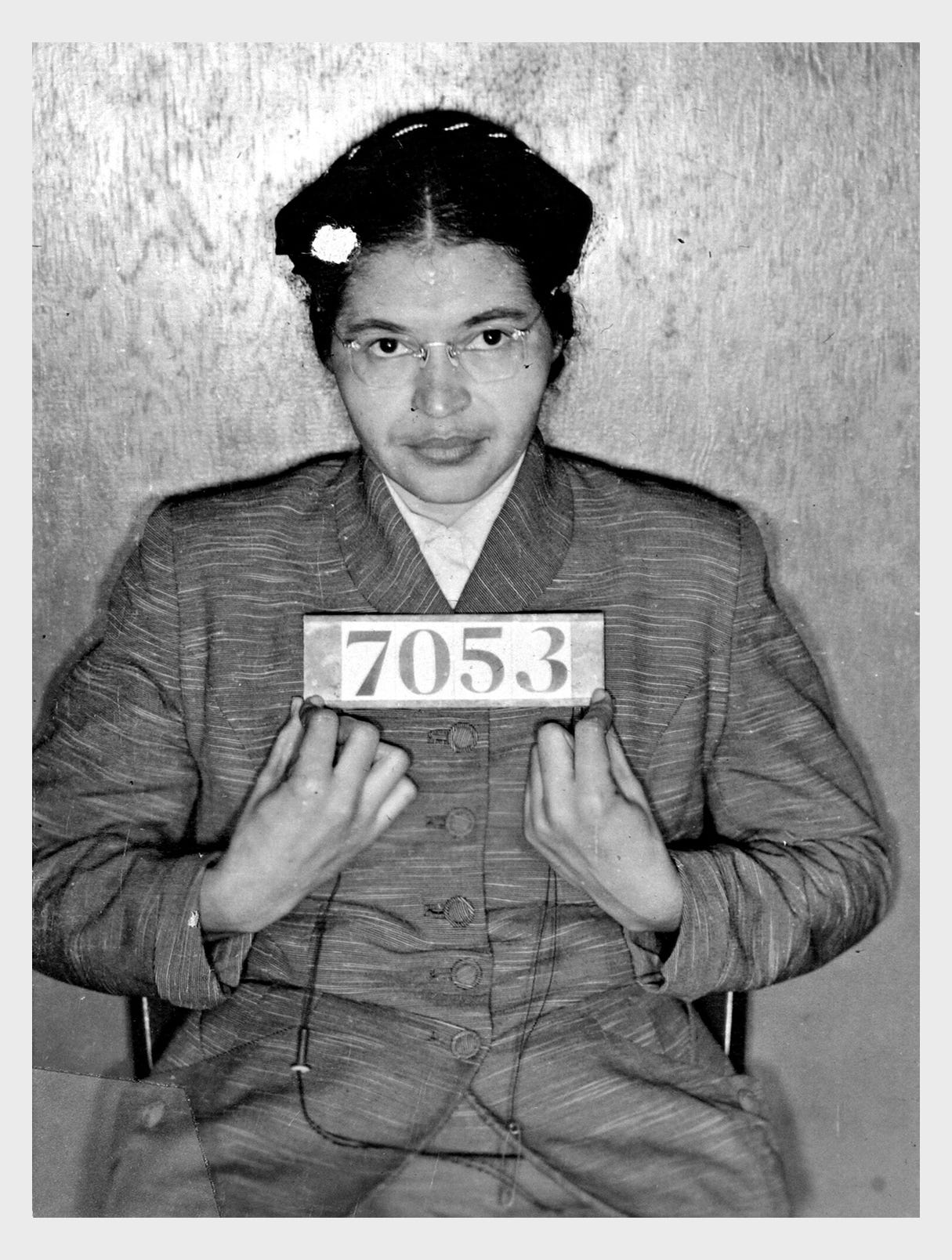

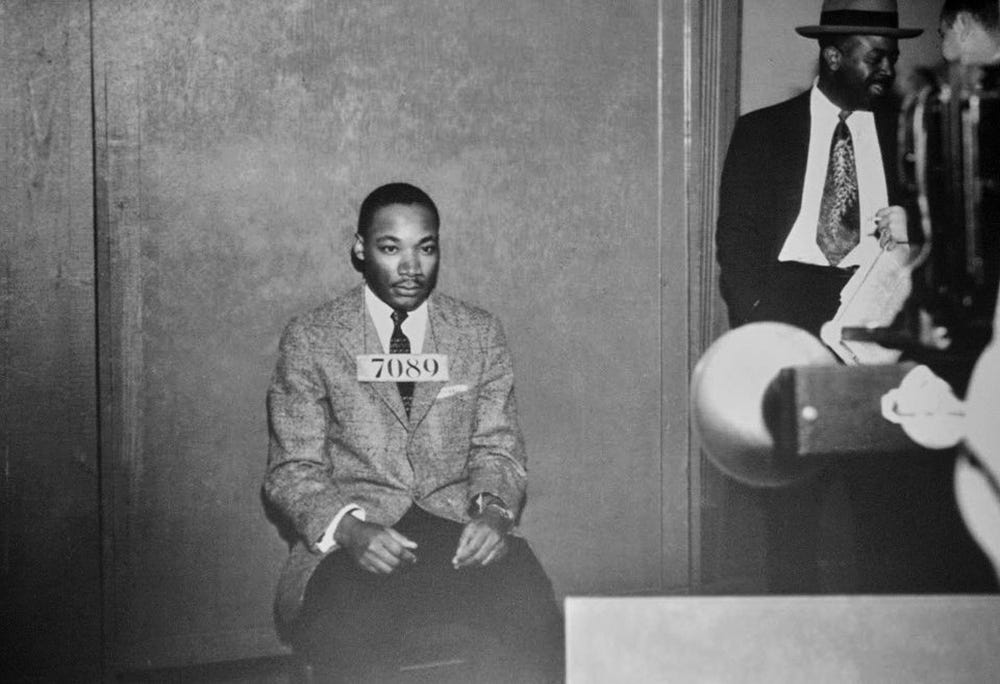

On the polar-opposite end of the mug shot spectrum is this photo of Martin Luther King, Jr., taken by the Montgomery County Sheriff’s Department on February 1, 1956.

King was arrested for organizing the Montgomery Bus Boycott, which was inspired by another person arrested that day: Rosa Parks.

Criminals? Hardly. Their mug shots became symbols of resistance against segregation and oppression, galvanizing support for the civil rights movement.

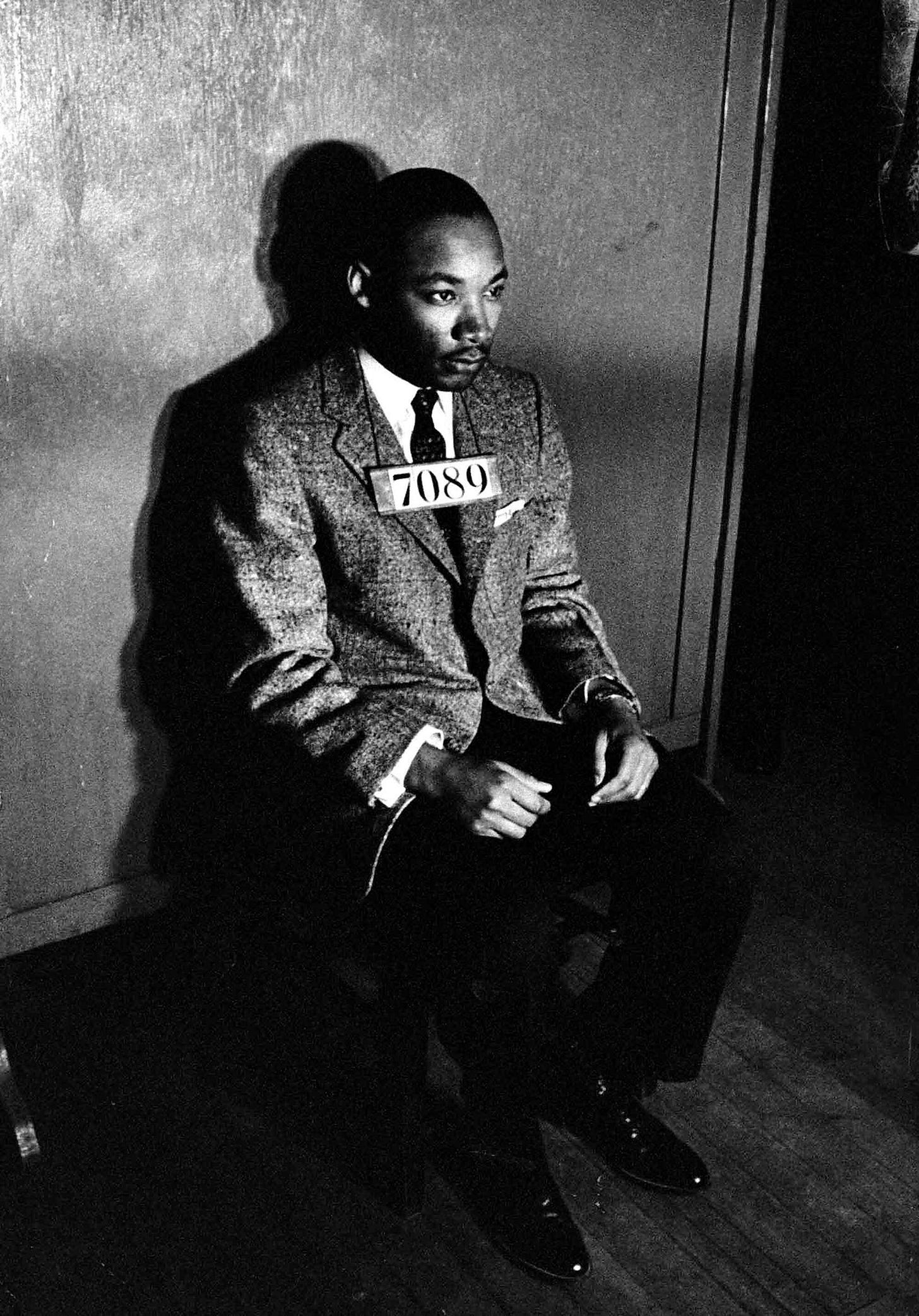

Interestingly, King’s experience was documented by two photographers that day — not just the police officer behind the mug shot camera.

LIFE magazine’s Don Cravens photographed King glaring defiantly into the police camera, an ominous shadow casted on the wall behind him.

King’s hands are a notable, telling detail. Another, even more interesting angle, was captured by TIME magazine freelancer Paul Robertson.

The addition of the man in the hat, smiling, adds another dimension to the photo, as well as the flash jutting into the frame. Robertson, when describing the image in 2014, said, “It was just another photo to me at the time. None of us, and I mean us whites, really had any sense that the world was changing. I was just taking pictures.”

There’s a short clip of King’s arrest in the 1970 documentary King: A Filmed Record... Montgomery to Memphis.1

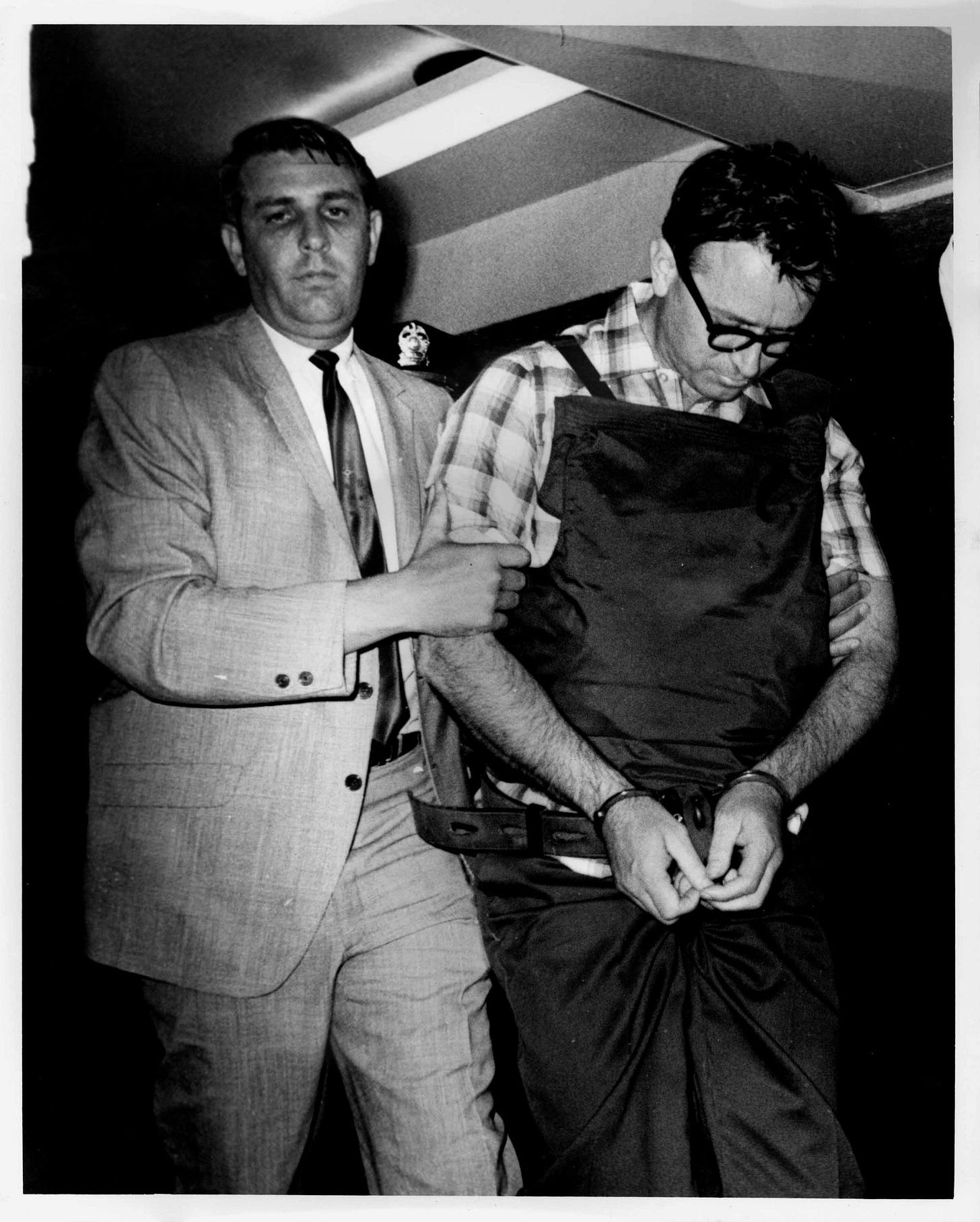

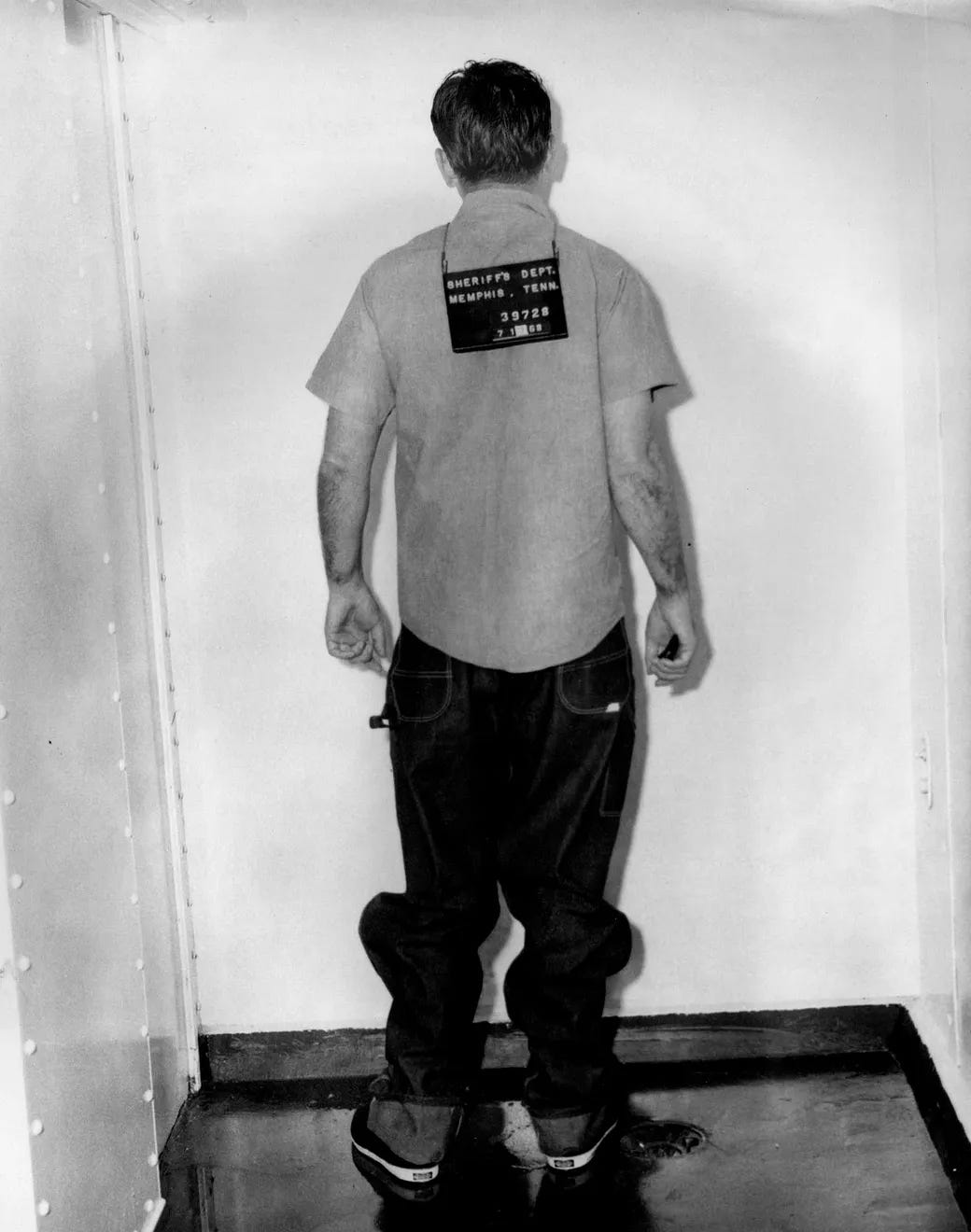

On April 4, 1968, King was assassinated in Memphis by white supremacist James Earl Ray. After Ray’s arrest, Shelby County Sheriff Bill Morris hired a photographer, Gil Michael, to document his incarceration and white-glove treatment July 19, 1968. The Sheriff’s department released only one photo by Michael, uncredited. Note the bulletproof vest.

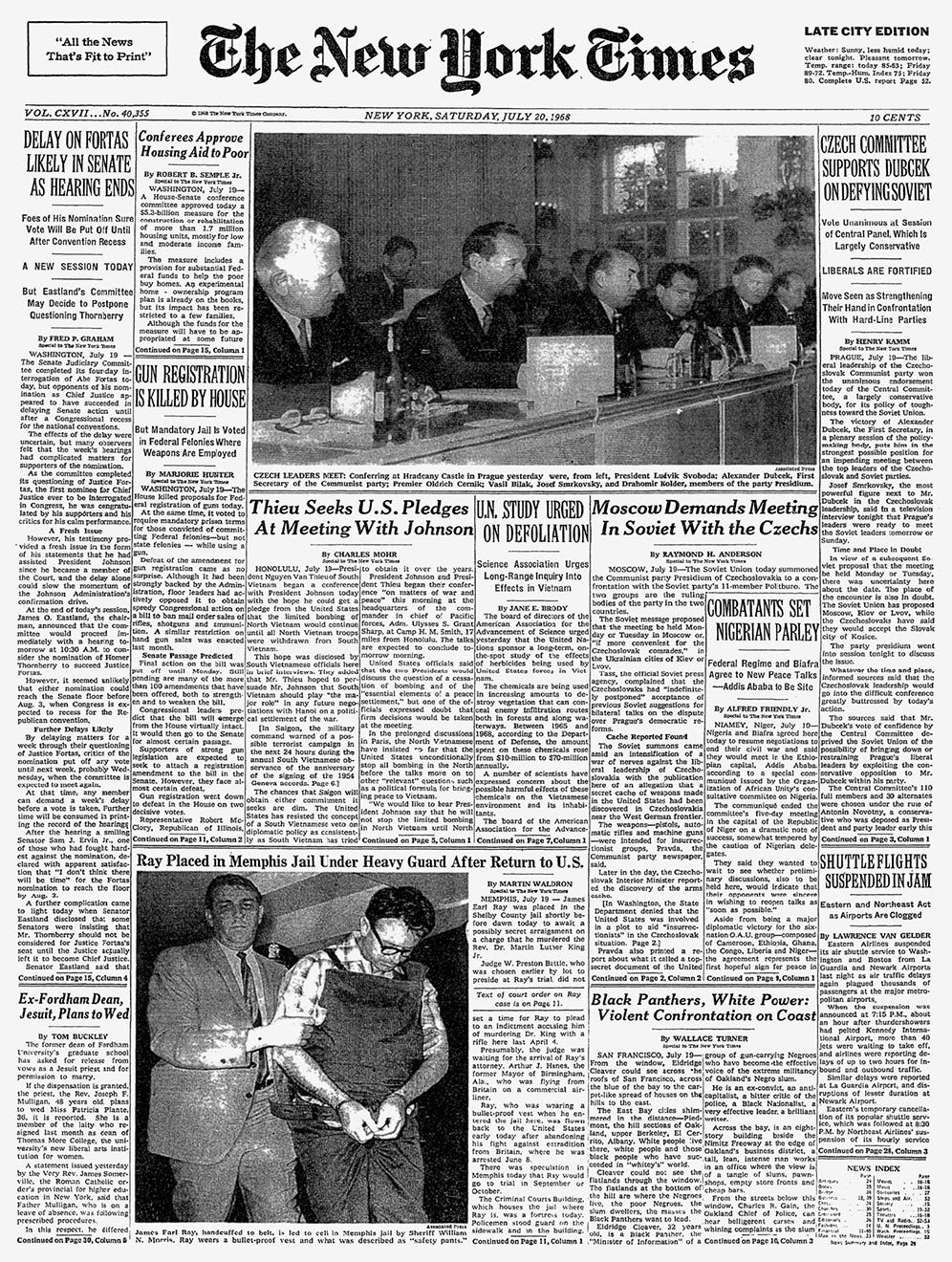

Michael’s photo landed on Page One of The New York Times, Saturday, July 20, 1968.

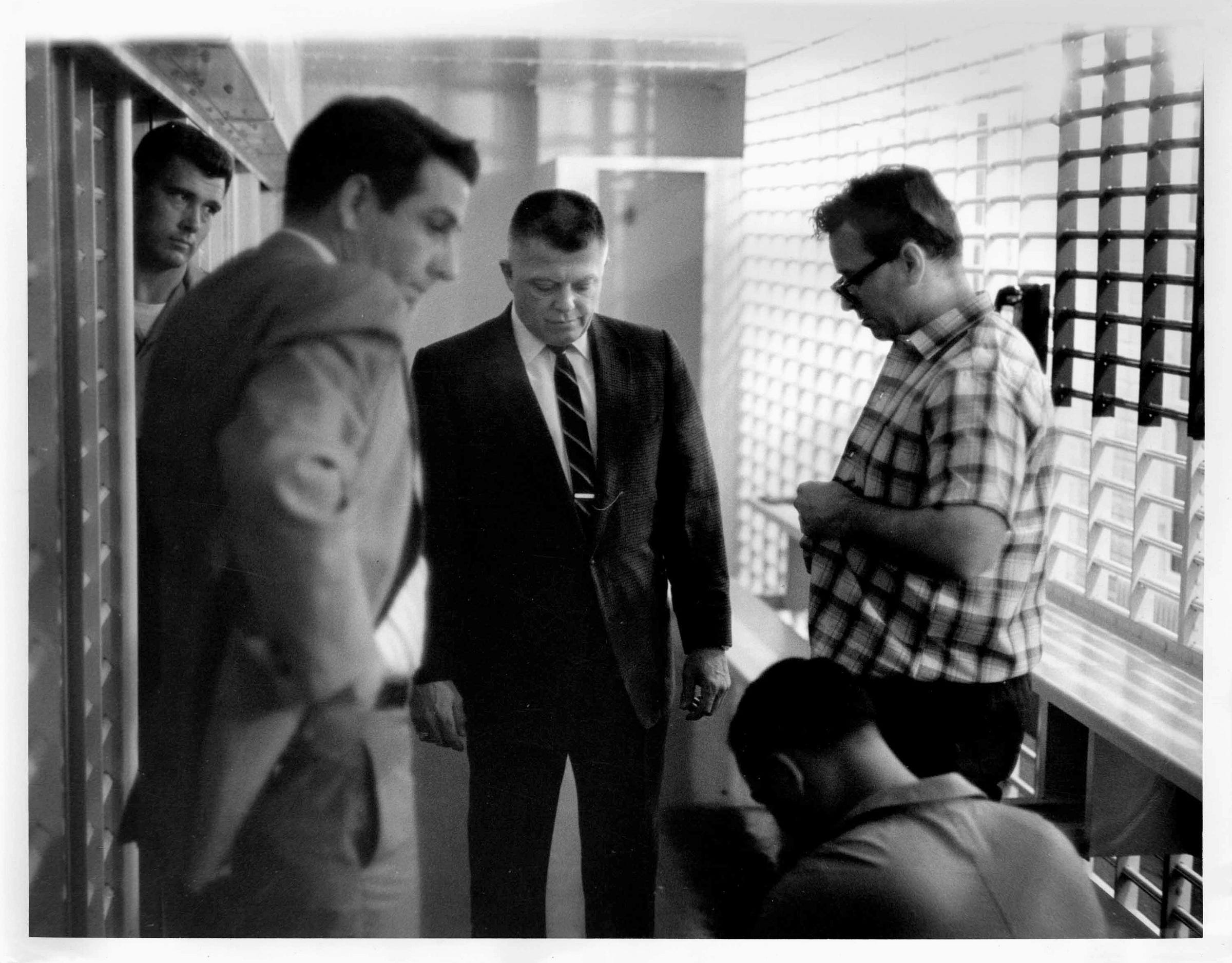

The rest of Michael’s photos sat in the Shelby County archives for decades, unseen until 2011, when they were, oddly, released to mark the forty-third anniversary of King’s murder.

“Ray must have had some problem with the press, because no sooner did I enter the elevator with him, did he attack me,” Michael recalled to CBS News in 2011. “He was upset that I was shooting the pictures. I saw a big foot was headed right for my face. He grazed my shoulder with his foot and cursed me out.”

Of Michael’s newly-released photos was one of the most bizarre mug shots I’ve ever seen. Behold, the anti-mug shot.

The sheriff insisted Ray wear a bulletproof vest and shielded him from the public as much as possible after his arrest, mindful of what had happened to Lee Harvey Oswald five years earlier.

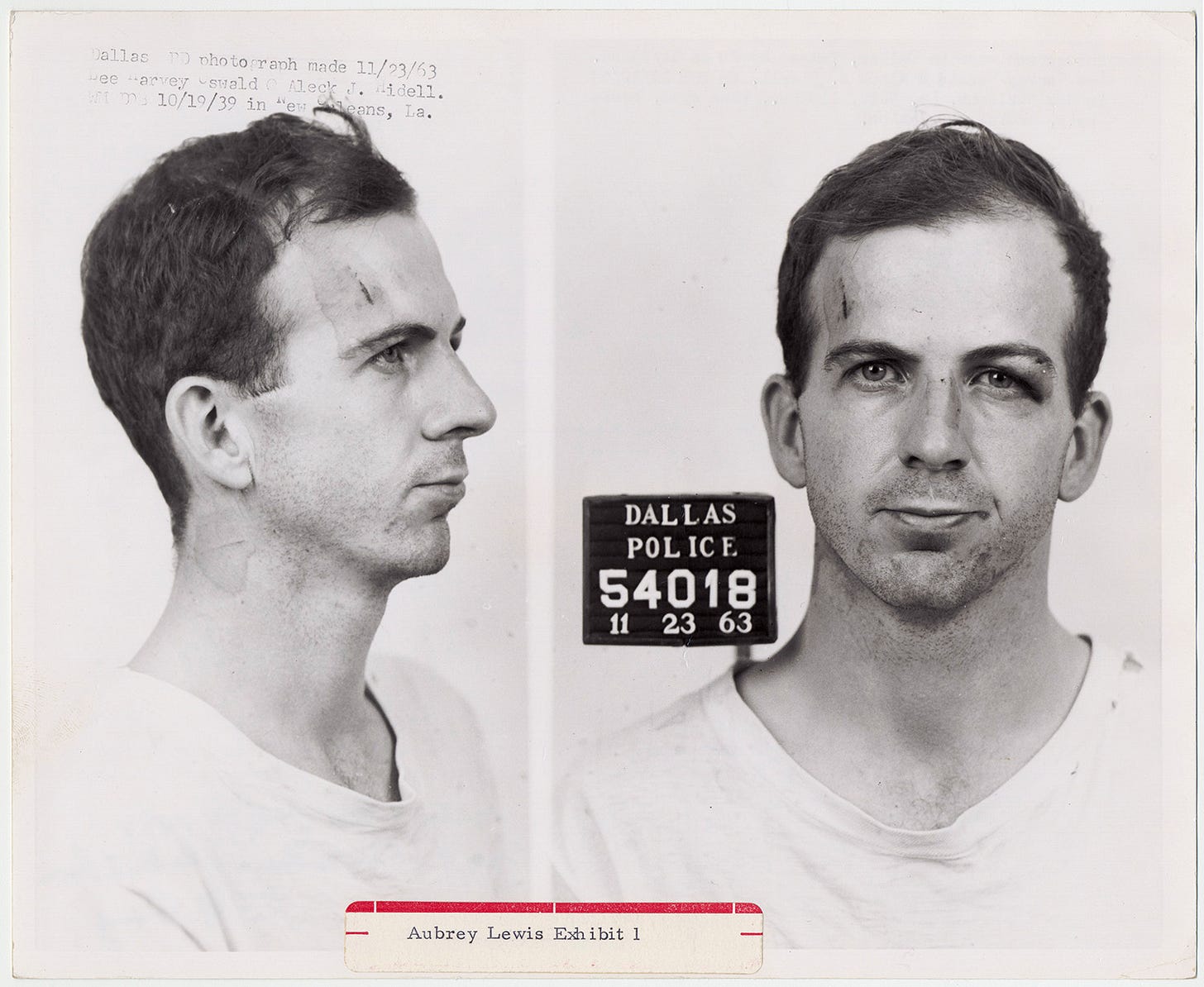

Speaking of Oswald…Aubrey Lewis was the Dallas police officer tasked with photographing JFK’s assassin after his arrest on November 23, 1963. This image was later released to the public and became known as “Aubrey Lewis Exhibit 1.”

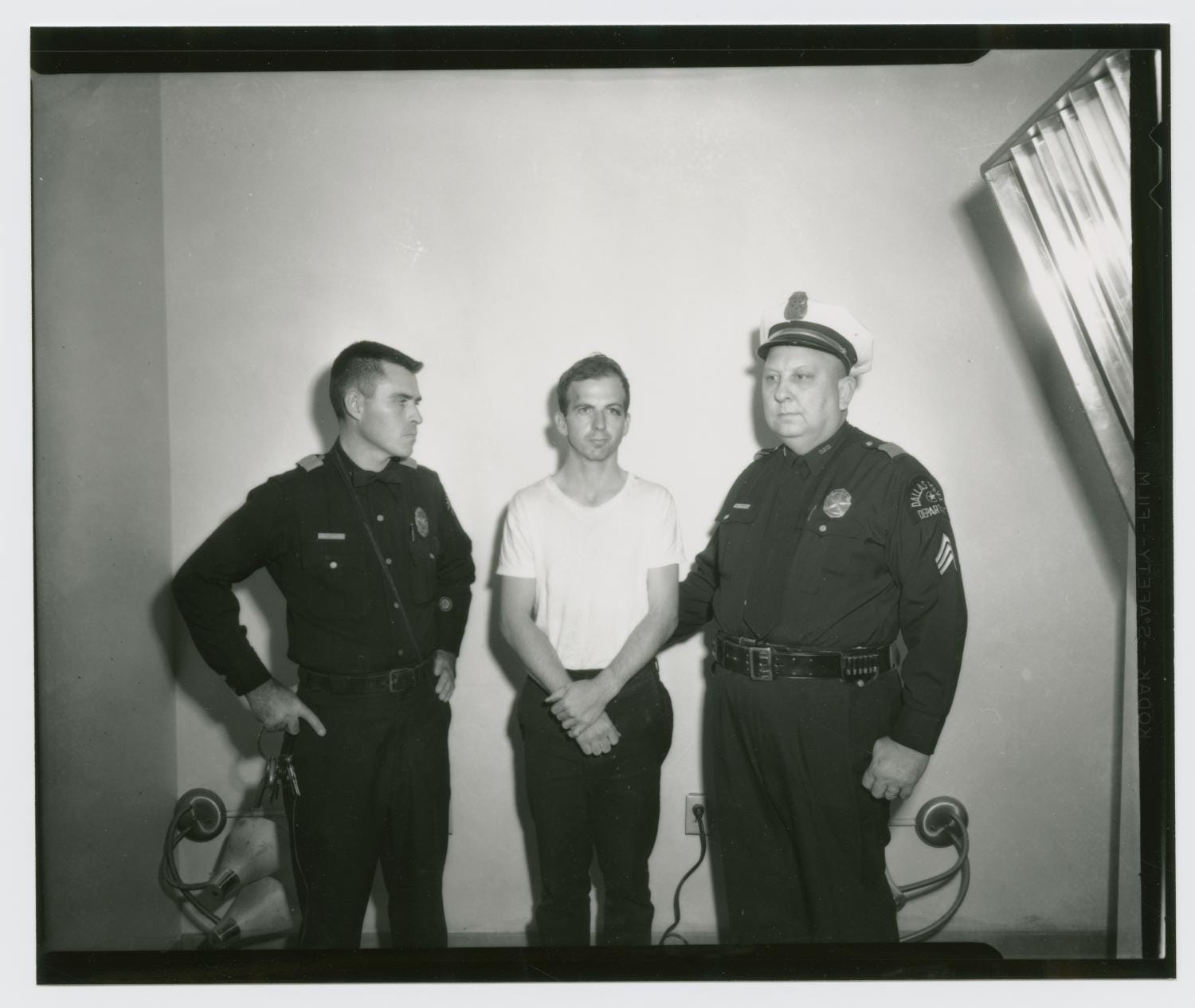

Lewis also captured this provocative, unintended moment inside the police station. Consider the body language and expressions.

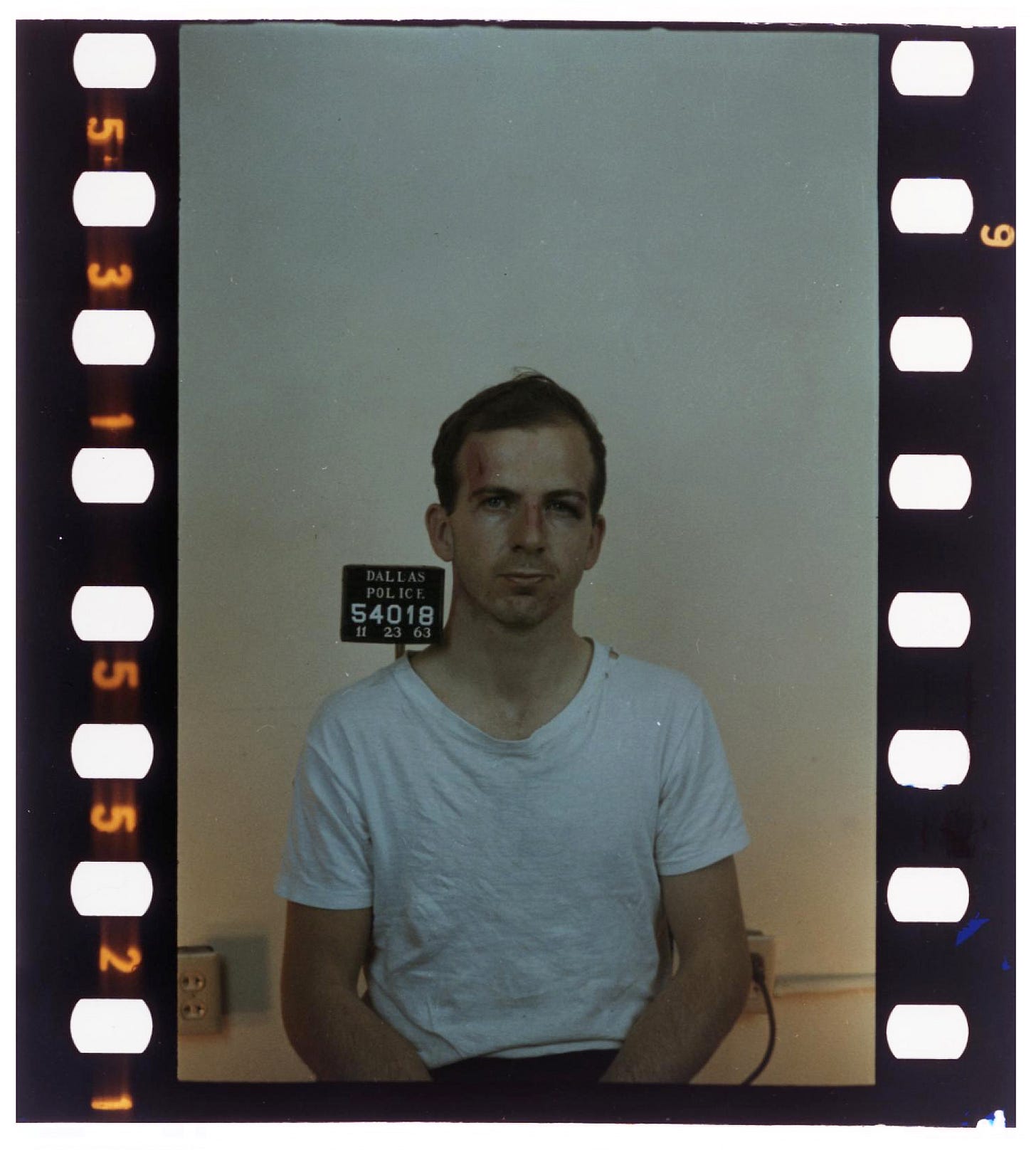

I was previously unaware of this slightly-underexposed color mug shot of Oswald.

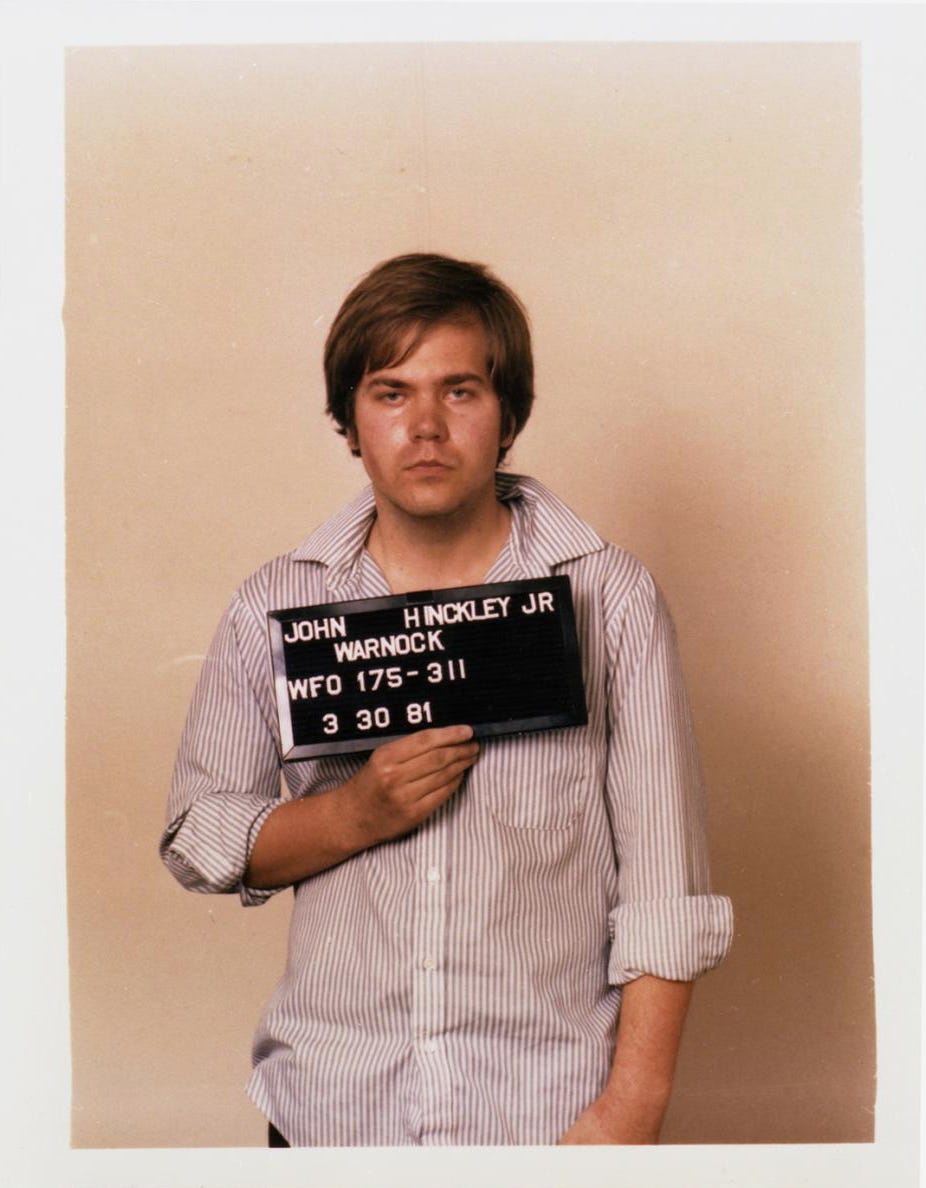

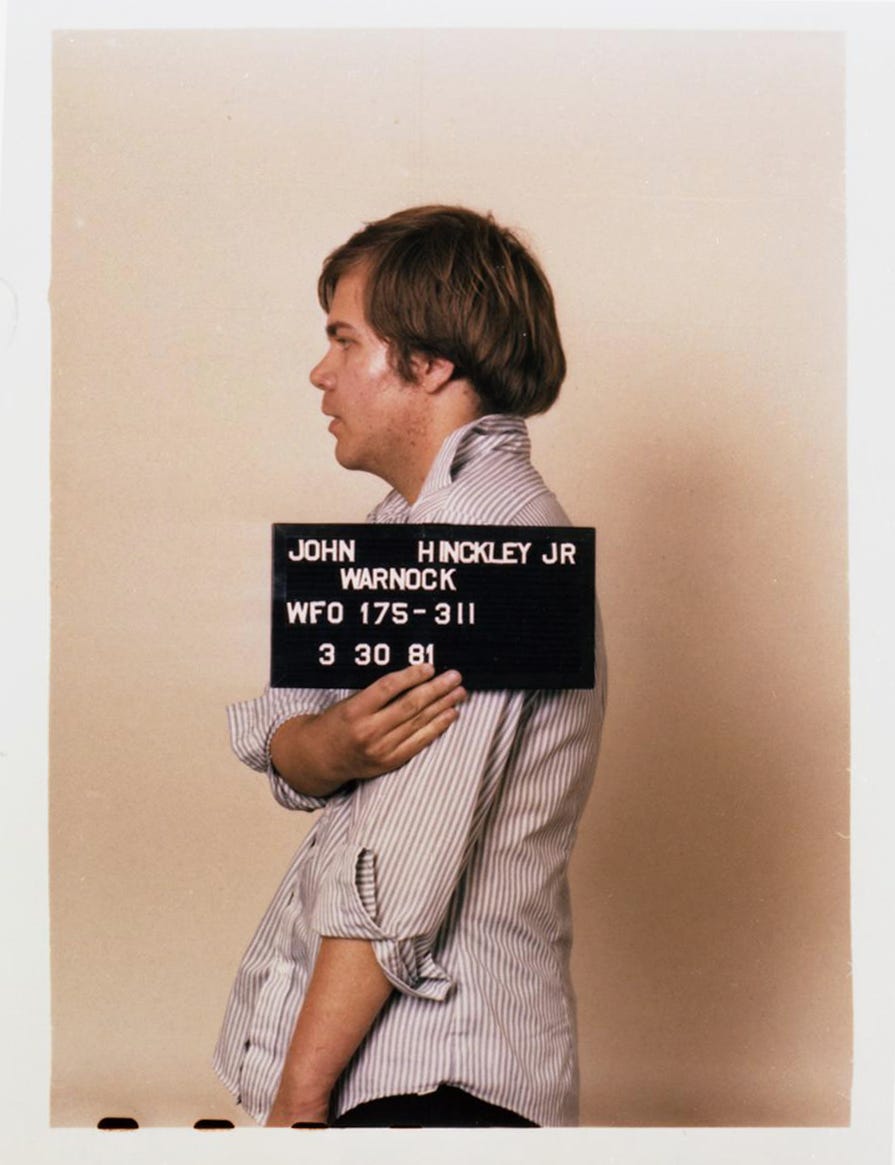

This mug shot of John Hinckley, Jr., was taken by the FBI on March 30, 1981, shortly after he attempted to assassinate President Reagan.

These photos are from the fascinating John Hinckley, Jr. Collection at the Ronald Reagan Presidential Library. More on that in the future.

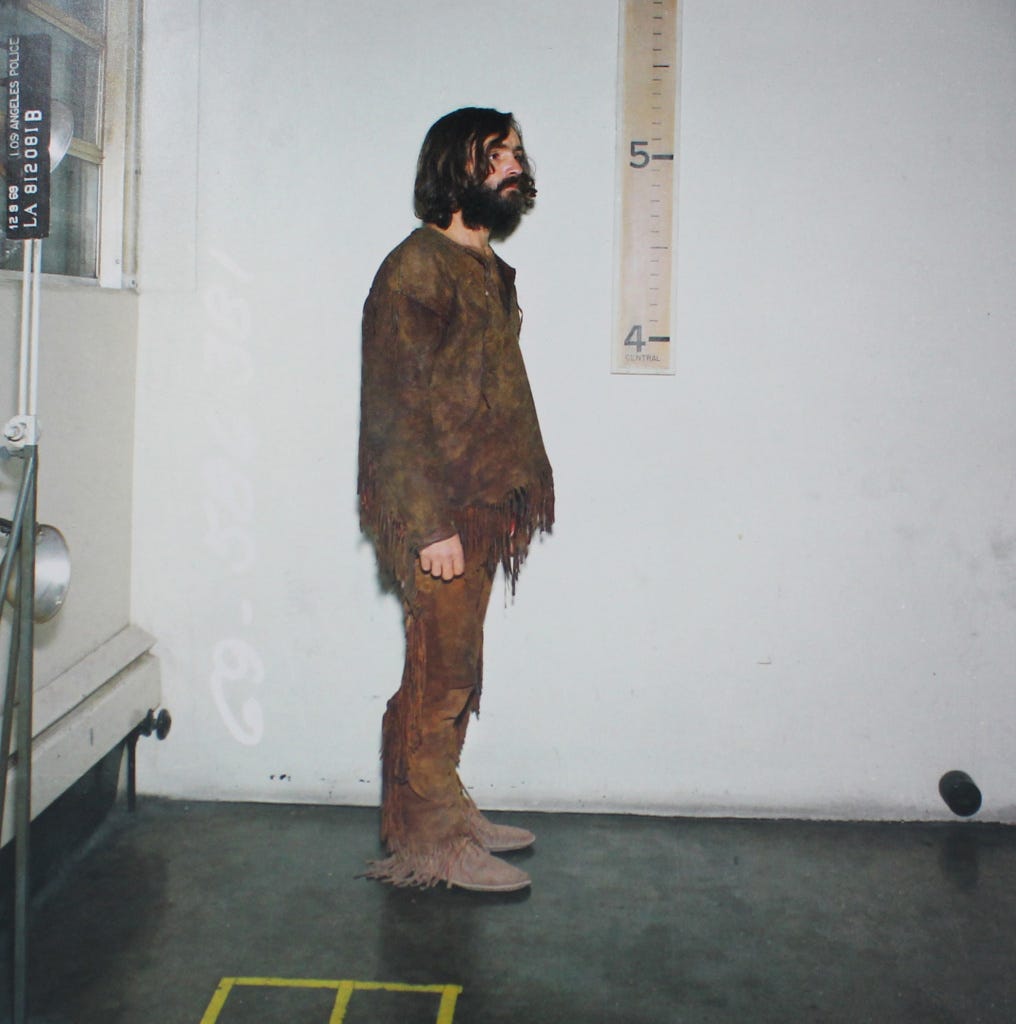

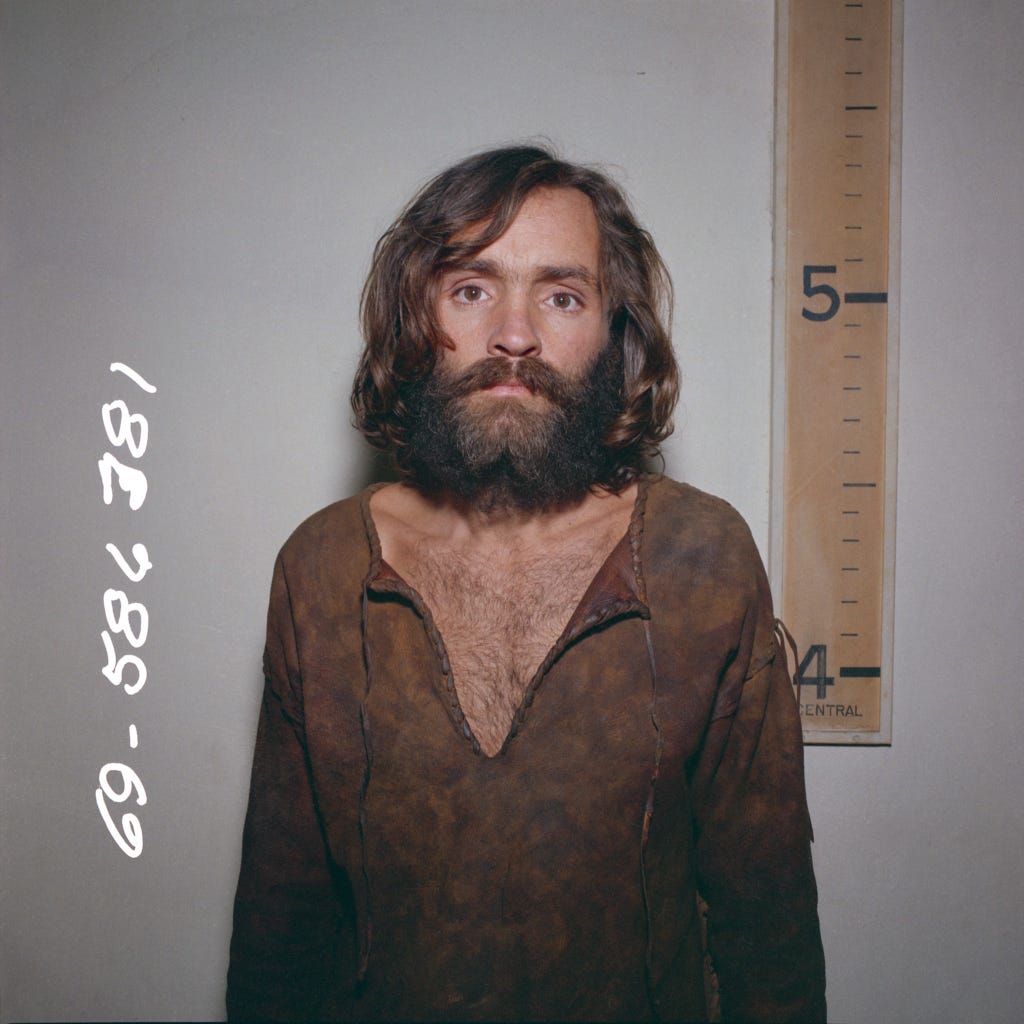

Echoing the anti-mug shot of James Earl Ray, the Los Angeles Police Department made this bizarre mug shot of Charles Manson after his arrest on December 9, 1969.

In many ways, Manson’s many mug shots catapulted him to fame. This session, Manson’s last before his conviction, was much more subdued.

LIFE magazine chose an older, more wild-eyed Manson mug for their December 19, 1969 cover.

That mug shot from the Ventura County Sheriff’s Department became iconic. Maybe because his height, 5’2”, isn’t shown?

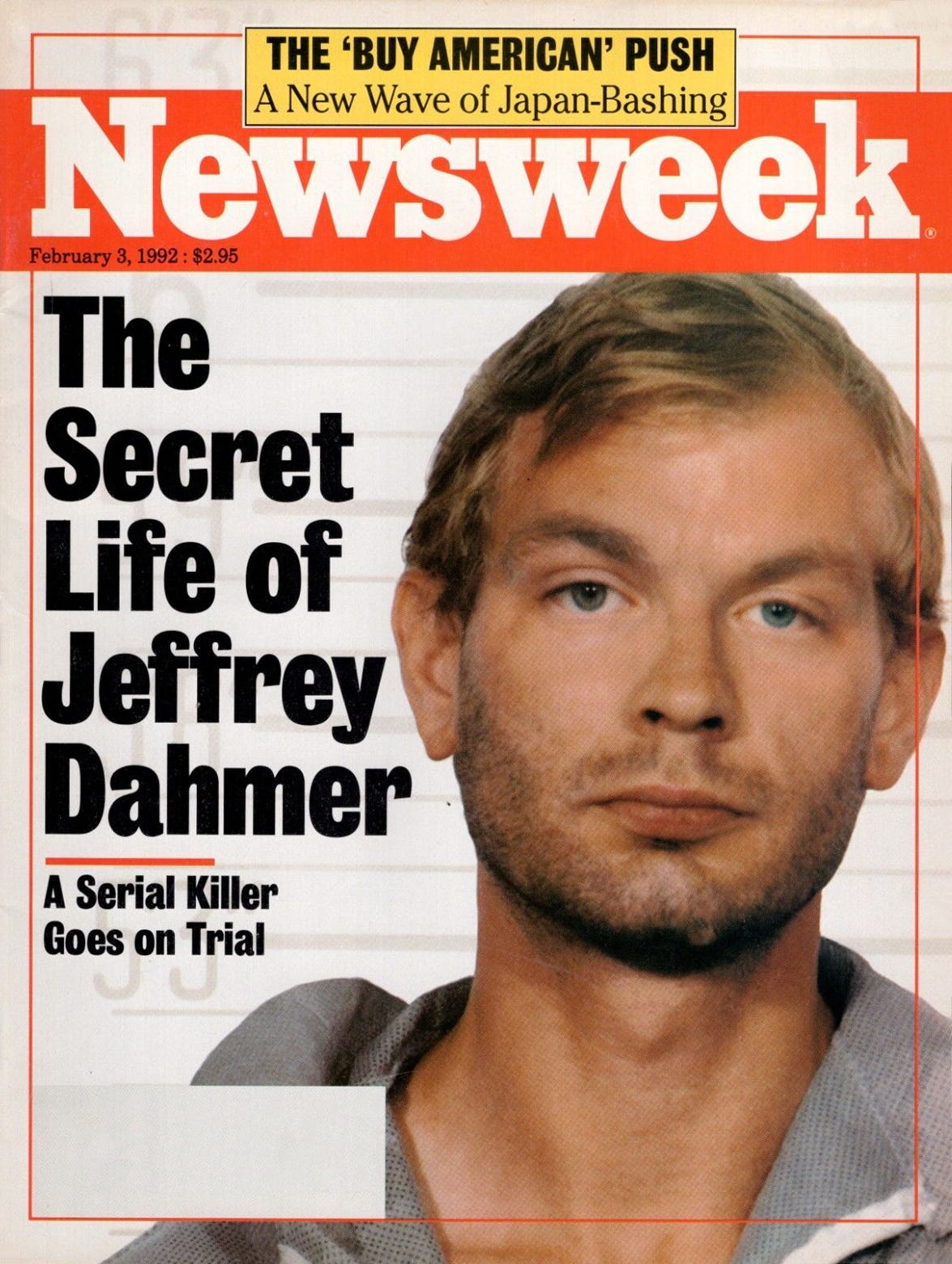

In 1992, Newsweek published the mug shot of another mass murderer on their cover — Jeffrey Dahmer.

The Milwaukee Police photographed Dahmer on July 23, 1991, the day after his arrest. Dahmer admitted to the murders of 17 men and boys between 1978 and 1991. He was sentenced to life plus 150 years in prison but was murdered by a fellow inmate in 1994.

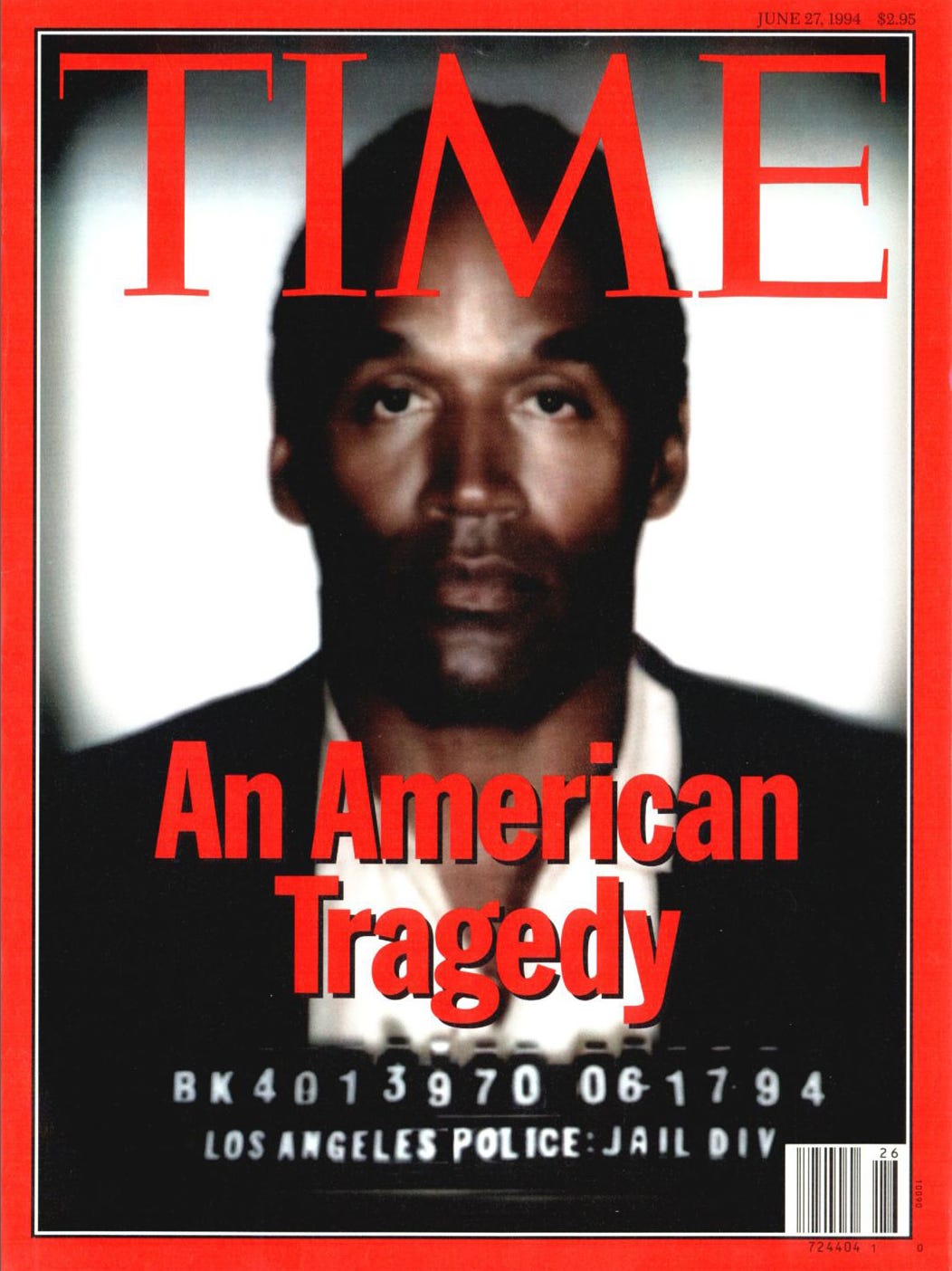

It’s impossible to have a conversation about mug shots and magazine covers without discussing TIME magazine’s infamous 1994 cover.

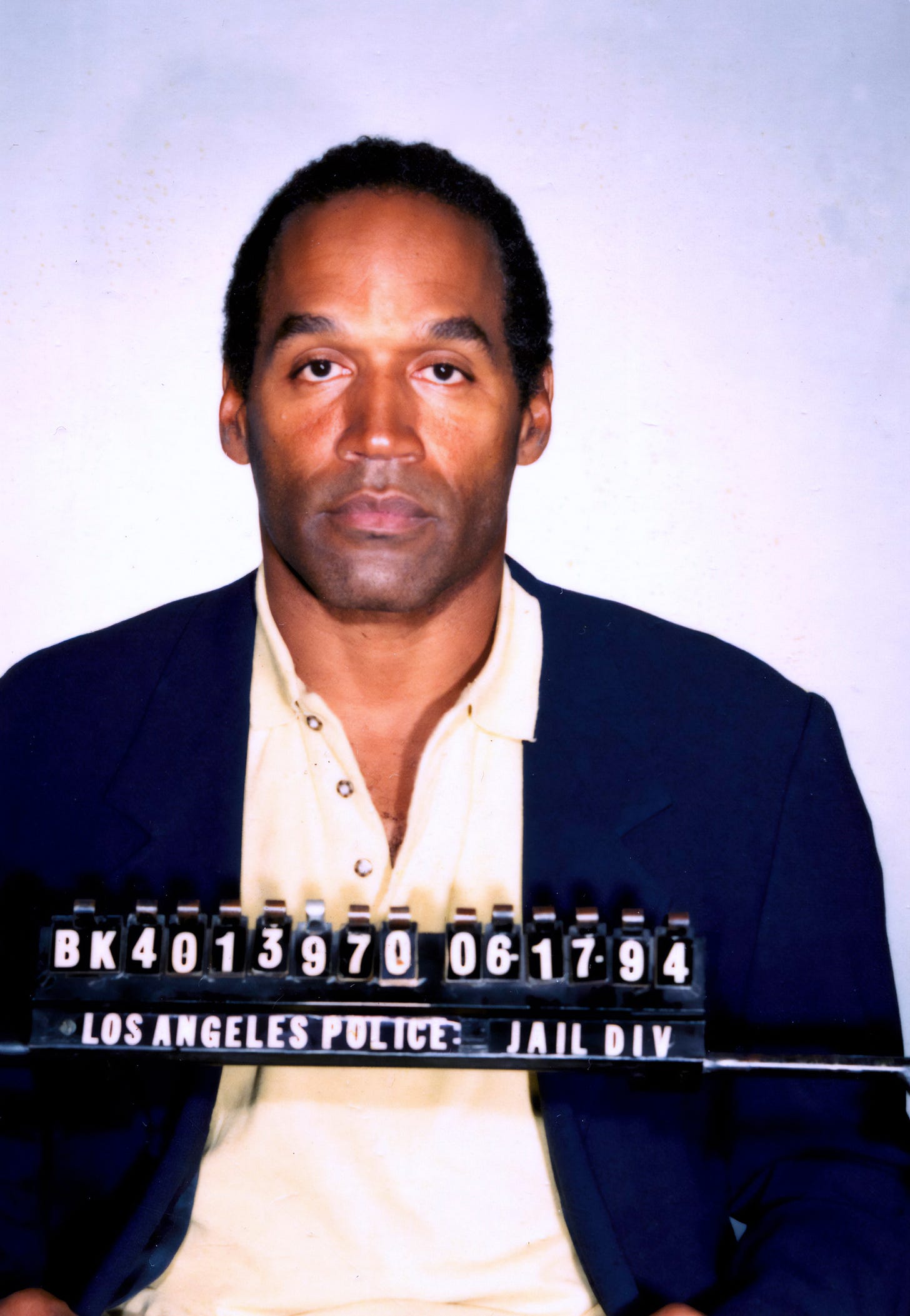

The Los Angeles police department released this mug shot of O.J. Simpson at 2 a.m. EST on Saturday, June 17, 1994 — a few hours before TIME’s deadline.

TIME had commissioned a painting of Simpson for the cover but once the mug shot landed, they scrapped that and turned to photo-illustrator Matt Mahurin.

“He had only a few hours, but I found what he did in that time quite impressive,” TIME’s editor, Jim Gaines, wrote, in a letter to readers. “The harshness of the mug shot — the merciless bright light, the stubble on Simpson’s face, the cold specificity of the picture — had been subtly smoothed and shaped into an icon of tragedy. The expression on his face was not merely blank now; it was bottomless. This cover, with the simple, nonjudgmental headline ‘An American Tragedy,’ seemed the obvious, right choice.”

“I have looked at thousands of covers over the years and chosen hundreds. I have never been so wrong about how one would be received,” Gaines continued in his letter, which is worth revisiting.

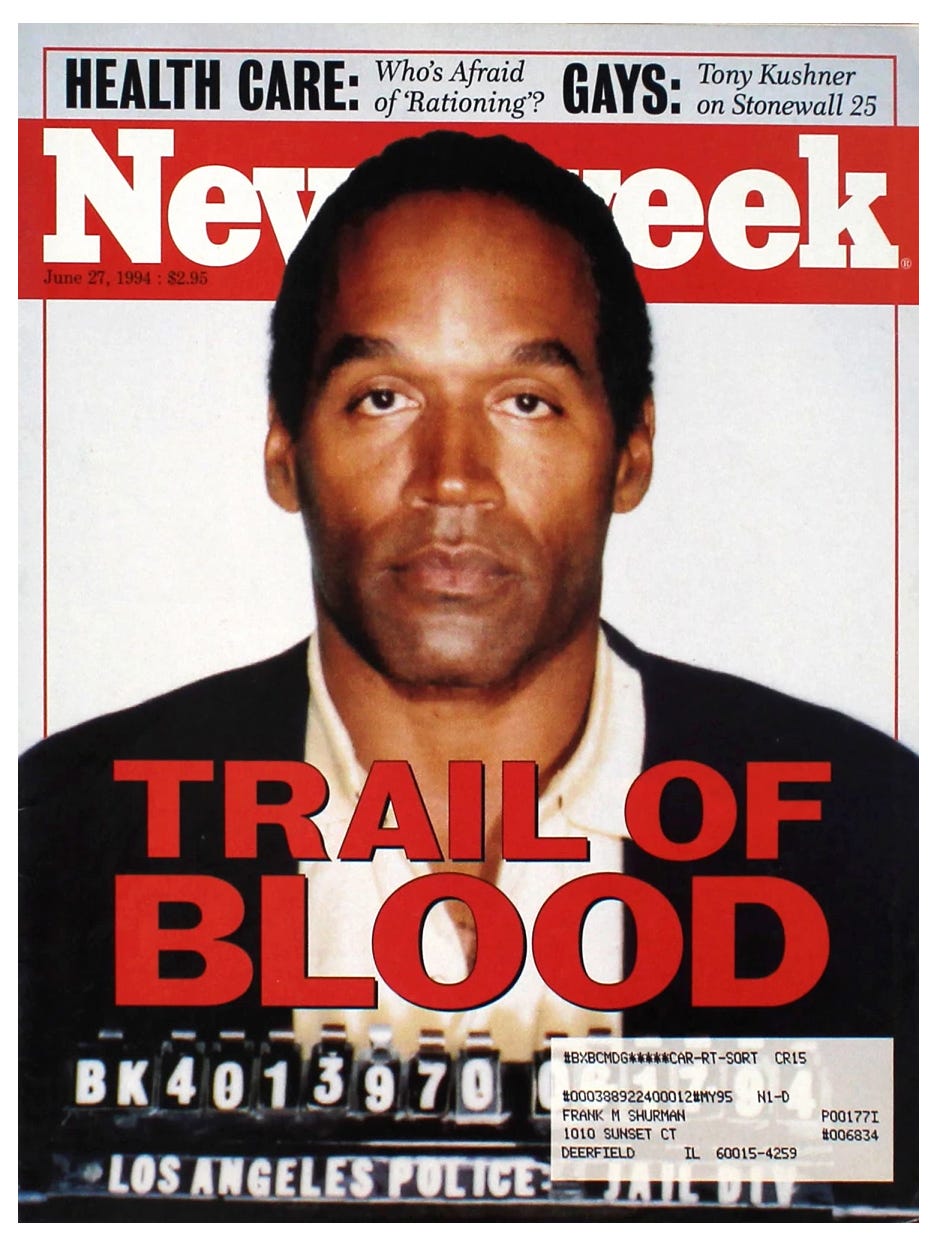

The fallout was immense. The severity of Mahurin’s treatment of the mug shot was highlighted by the fact Newsweek ran the photo as-is.

Mahurin, unfairly I believe, bore the brunt of the criticism. That’s his aesthetic — dark and gloomy, moody, heavy-handed. Mahurin gave TIME exactly what they hired him for, and therein lies the problem.

The mug-shot-as-art was realized long before TIME fumbled with O.J. In 1865, after the assassination of President Lincoln, the head of the secret service turned to photographer Alexander Gardner, a former assistant to Mathew Brady, to document the investigation. Gardner meticulously photographed every detail, from the mug shots of the conspirators to the moment of their execution.

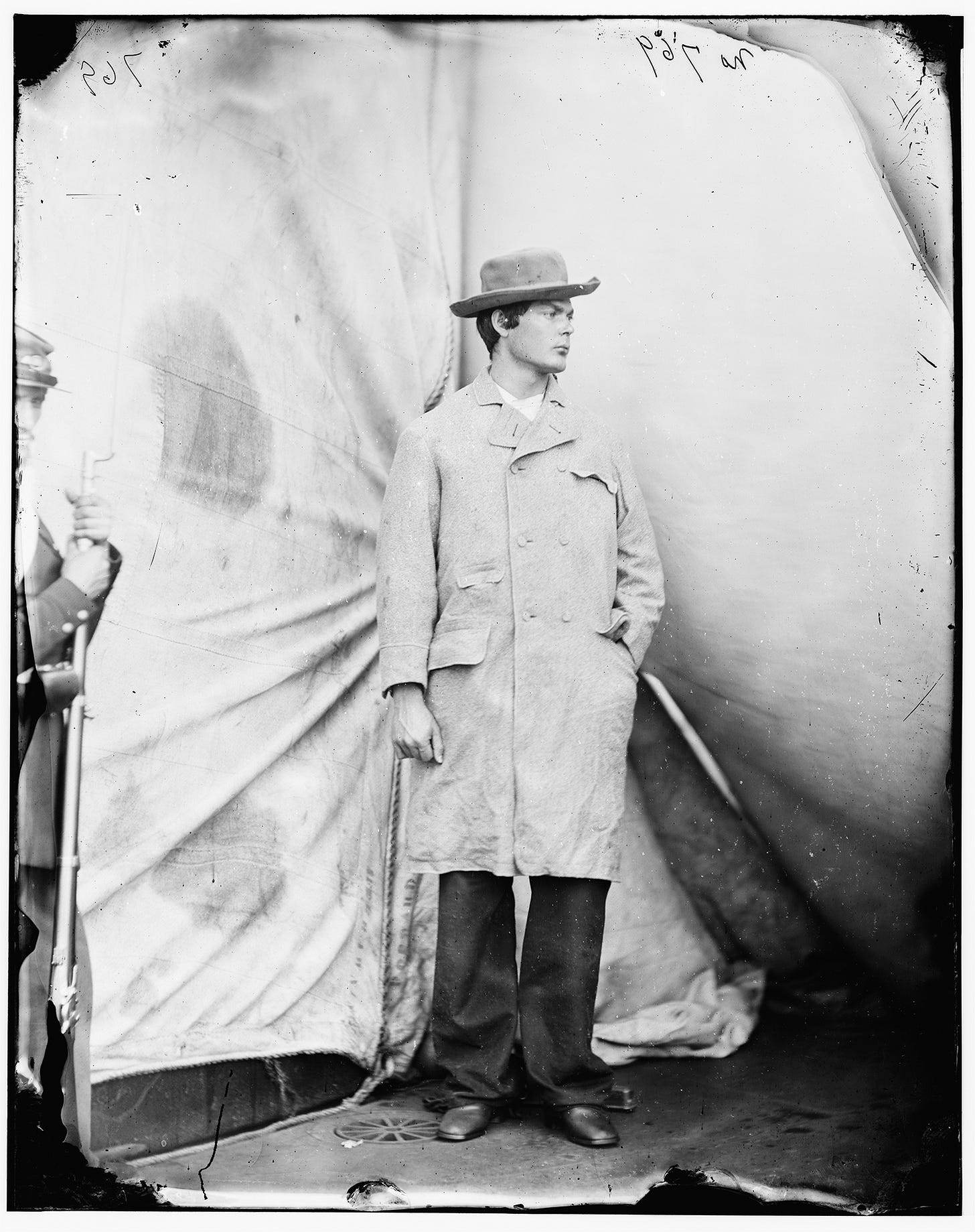

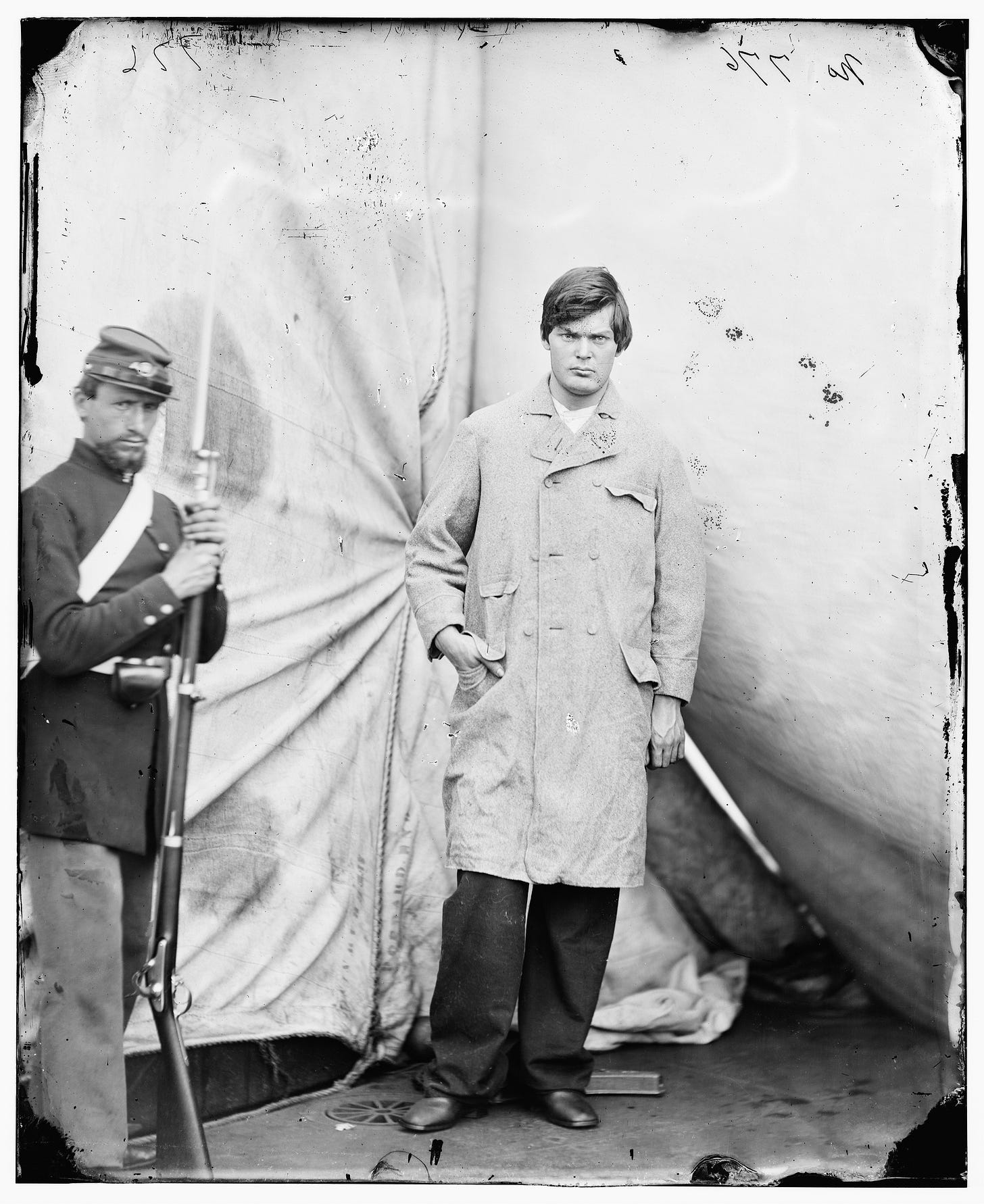

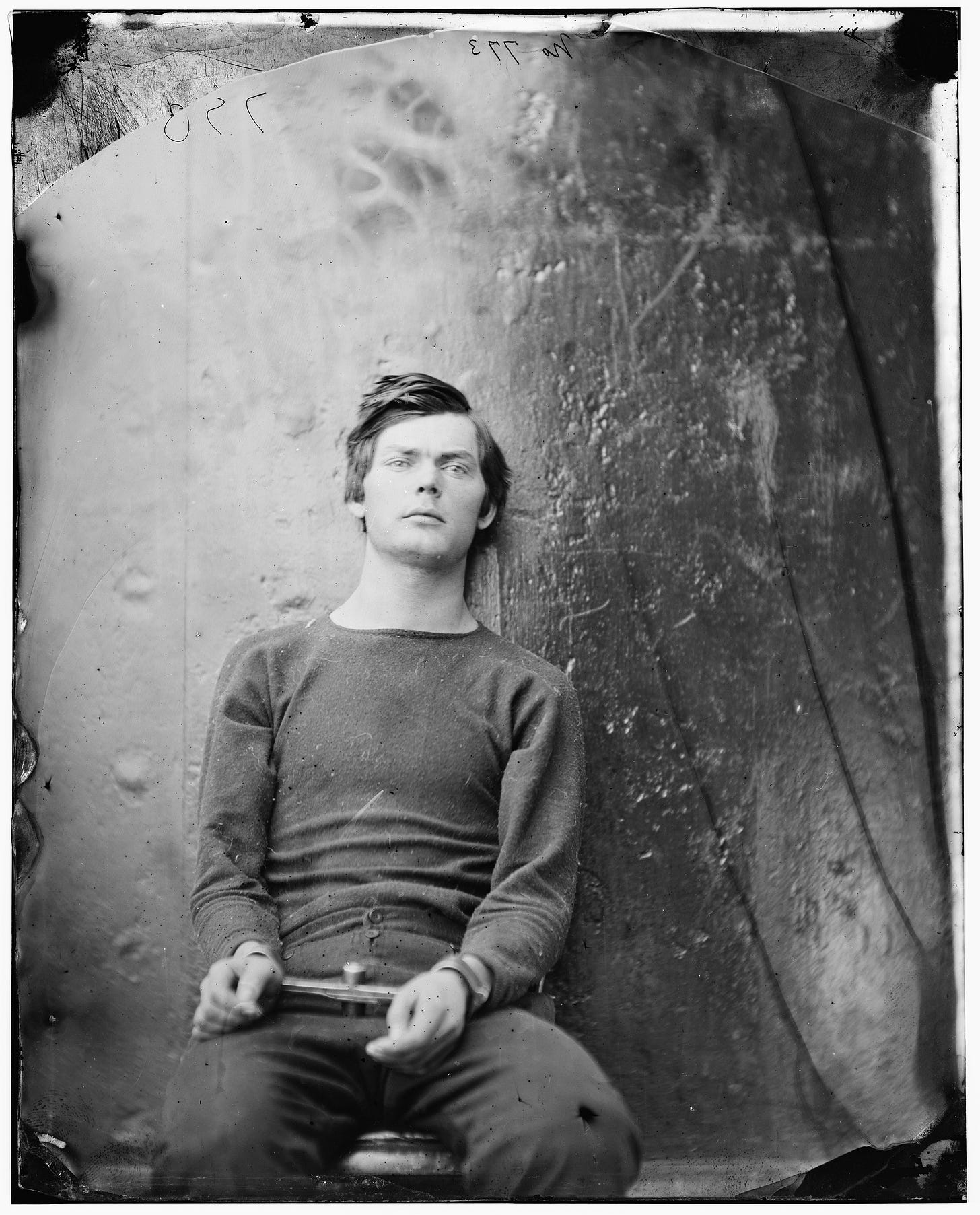

One of Gardner’s most compelling subjects was Lewis Payne, aka Lewis Paine, aka Lewis Powell. While John Wilkes Booth was busy assassinating Lincoln, Payne attempted to murder Secretary of State William Seward, but failed. After his arrest, Payne was held with the other conspirators aboard the U.S.S. Montauk and U.S.S. Sauger.

On April 27, 1865, using the wet plate collodion process, Gardner made at least 10 photos of Payne.

Gardner’s image of Payne in captivity aboard the Montauk was the basis for an illustration on the cover of Harper’s Weekly magazine, May 27, 1865.

“Like almost everyone else, Gardner was apparently fascinated with Lewis Paine,” Mark Katz wrote. “Gardner also set a precedent by taking one frontal photograph of each conspirator and another in profile, which eventually became standard law-enforcement practice.”2

Payne’s hand in the pocket is a riveting detail, almost as if he’s going for his gun.

In my opinion, Gardner’s portraits of Payne are the most beautiful, unsettling, artful mug shots portraits ever made.

Trump's low-res, poorly-lit, mug shot is a far cry from the artistry and craft often seen in mug shots of the past, as unintentional as that may have been.

Maybe it’s time for the mug shot to die, though that’s unlikely.

To borrow a phrase from longtime curator Sandra Phillips: We need mug shots, because they are not of us.3

Joseph L. Mankiewicz, Sidney Lumet, dir. King: A Filmed Record... Montgomery to Memphis. 1970. Streaming on CuriosityStream.

Mark Katz, Witness to an Era: The Life and Photographs of Alexander Gardner. (New York: Penguin Group, 1991), 164.

Mark Haworth-Booth, Sandra S. Phillips, Carol Squiers, Police Pictures: The Photograph as Evidence. (San Francisco: Chronicle Books, 1997), 11.