The Flag Is A Force That Gives Us Meaning

Throughout history, flags have elevated the emotional impact of images, attracting photographers — and photo editors — like moths to a flame.

On April 5, 1976, as an angry mob of white, anti-busing demonstrators violently descended on a black lawyer, Boston Herald American photographer Stanley Forman could hear the motor drive on his Nikon F failing. Amid the chaos of flying punches and kicks, Forman’s instincts took over — he switched to manual and squeezed the shutter just in time to capture the moment Joseph Rakes attacked Ted Landsmark with an American flag.

“I didn't know they were going to get him with a flag. I don't even remember seeing the flag,” Forman told the Boston Globe in 2001. “It was just: Bang! They're going to get him.”1

Forman’s negatives reveal the motor drive was not fully advancing and how close he came to missing the picture of a lifetime. The American flag slowly creeps into the frame.

The Soiling of Old Glory won Forman his second consecutive Pulitzer Prize, solidifying his place next to Weegee on the Mount Rushmore of spot news photographers. The image is most often seen with this heavy, but necessary, crop — hardly, in the words of Henri Cartier-Bresson, a “death to the geometrically correct interplay of proportions.”2

Forman’s photo has drawn comparisons with Peter Paul Rubens’ Le Coup de Lance. I can see why — the spear, the body language, the reactions — but the Roman soldier’s red cape just doesn’t carry the same weight as the Stars and Stripes.

Forman made a hell of a photo, a near-miracle. The weaponization of the flag, aka the soiling, is unexpected and disturbing. But what if Joseph Rakes had left his family’s American flag at home? Would the photo resonate as deeply?

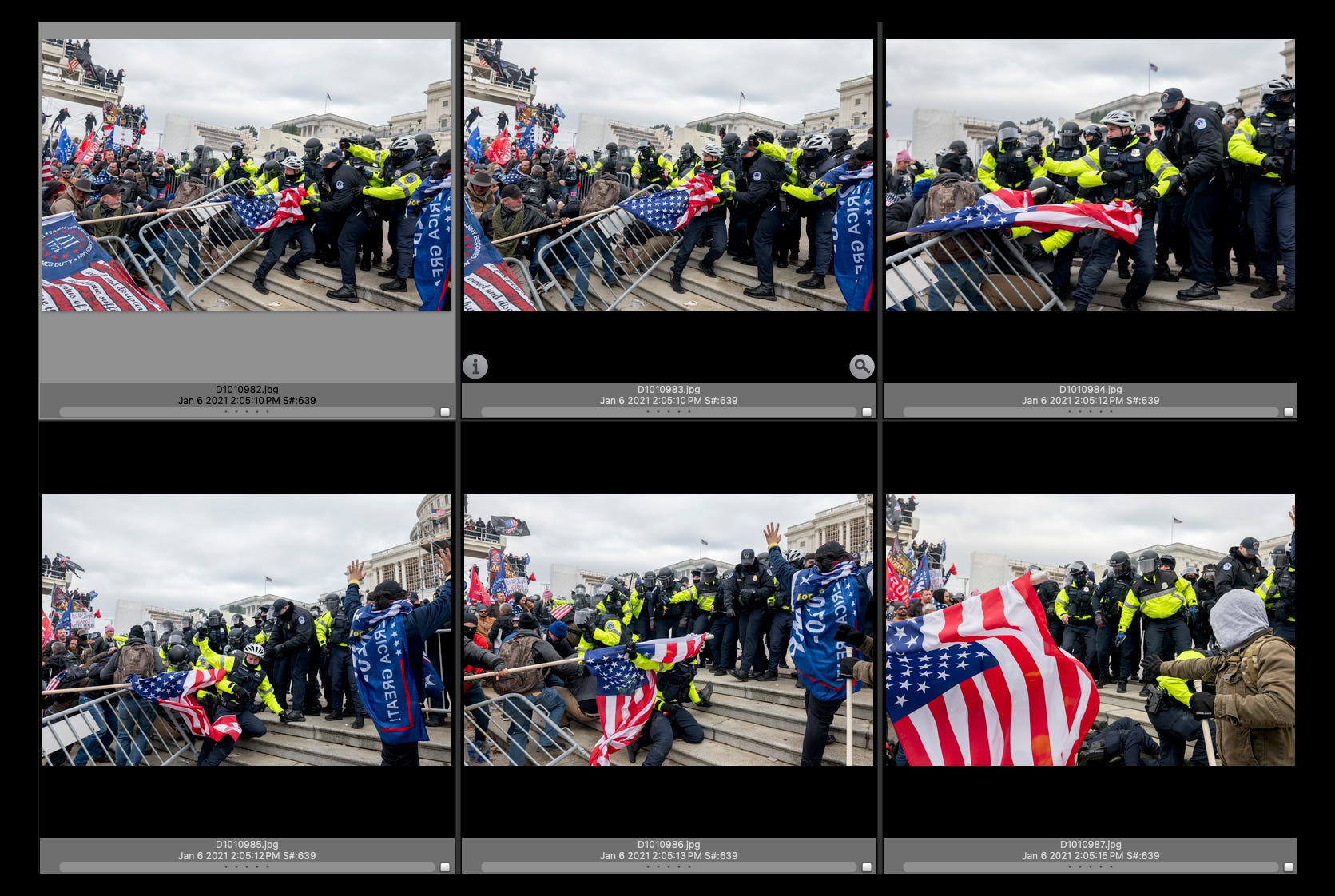

Nearly fifty years later, on January 6, 2021, a weaponized American flag was documented once again. David Butow’s unsettling photo from the steps of the Capitol is a modern echo of Forman’s Soiling of Old Glory.

The details are endless, this is truly a photo one can walk through. Let’s start with the obvious: the weaponized American flag, upside down — a symbol of distress — spearing a seemingly helpless police officer. Contrast this with the flag flying over the Capitol in the background, small, subtle, minimized. The attacker, later identified as 73-year-old Dale Huttle, is just out of frame, his anonymity symbolizing the frenzied crowd.

“I did notice the flag as I was shooting,” Butow told me. “I can't be sure, but I think I had, subconsciously, some reflection of Forman's picture which was packed into my head from my teenage years when I was first learning about photojournalism.”

Butow shared his sequence with me — the parallels with Forman’s photo are striking, especially in the first frame of Huttle spearing the officer. Butow's select for his book, Brink, was deliberate, including the man on the far right with his hands raised, wearing a Trump flag like a superhero.

On the opposite end of the emotional spectrum is the mother of all flag photos: Joe Rosenthal’s Raising the Flag on Iwo Jima.

On February 23, 1945, during the Battle of Iwo Jima, Associated Press photographer Joe Rosenthal and Newsweek reporter Bill Hipple overheard plans for soldiers to scale Mount Suribachi with an American flag. “The hell you say?” Hipple lit up.3

After weaving their way through a mine field, the journalists were joined by Marine combat photographers Pvt. Bob Campbell and Sgt. Bill Genaust. Halfway up the 500-foot volcano, still under fire, they crossed paths with Leatherneck photographer Louis Lowery, who told them they were too late — the flag was flying.

“When we heard that the flag had already been raised, we almost decided not to go on. But Lowery had said that it was a panoramic view of the island, so we decided to go on up,” Rosenthal recounted.

Lowery was correct — a flag had been raised, but it was only 4½ feet wide. But lucky for Rosenthal, a battalion commander had ordered a larger 8-foot-wide Old Glory borrowed from a beached Navy landing ship to replace the smaller flag, making sure Japanese soldiers could see it clearly from a distance.

Rosenthal and the others arrived just as the smaller flag, which I call the Lowery flag, was being replaced.

“The ground sloped down toward the center of the volcanic crater, and I found that the ground line was in my way. I put my Speed Graphic down and quickly piled up some stones and a Jap sandbag to raise me about two feet (I am only 5 feet 5 inches tall) and I picked up the camera and climbed up on the pile. I decided on a lens setting between f/8 and f/11, and set the speed at 1/400th of a second.”4

Raising the Flag on Iwo Jima was one of only 18 photos Rosenthal made that day. It wasn’t his favorite; this one was…

“I will accept that the flag-raising shot, for which I can take only such a small part of the responsibility, is the best picture I have ever made,” Rosenthal wrote. “Yet I have a special fondness for this other picture of the two dead Marines and the living one.

“The flag-raising picture…was accidental. In taking this other I had to make an effort to create out of honest ingredients, as much as you can create under fire, a truth, and to me it is a representation of man’s struggle, of the living taking over for the fallen dead because the battle must go on.”

Still, the importance and impact of Rosenthal’s photo can’t be overstated. It’s arguably the most famous photo ever — perpetually iconic — and the most lucrative fundraising tool for the U.S. military in history, raising over $26 billion in war bonds.

This epic poster, illustrated by C.C. Beall, certainly helped the cause.

Oh, and get this: Rosenthal’s bonus from the AP for his photo was a year’s salary — paid in War Bonds.

But what about the other photographers on Mount Suribachi with Rosenthal?

Pvt. Bob Campbell was positioned to the right of Rosenthal, and shot a photo a split second after him of both flags — the small one coming down and the big one going up. It’s monumental.

I love the chaos in Campbell’s photo — it’s far from perfectly composed, but that’s what makes it so interesting. The photo is a little confusing, asking more questions than it answers, which adds to the allure. It’s a slow read, unlike Rosenthal’s, but once you realize what’s happening, Campbell’s version of the flag raising becomes something…greater.

And Sgt. Bill Genaust? He was standing three feet to the right of Rosenthal, hand cranking 16mm color film. At :06, you can spot the base of the first flagpole. The speed of events is remarkable but fleeting — another testament to the power of the still.

Genaust was killed in action nine days later. His body was never recovered.

It took nearly 60 years for another photo to evoke a similarly profound, Rosenthal-esque vibe. In the aftermath of the terrorist attacks on September 11, 2001, Thomas E. Franklin documented three New York firefighters raising the American flag amid the wreckage of the fallen World Trade Center towers. Like Rosenthal’s photo, it was universally embraced, an uplifting photo that defined resilience and unity.

“It was unplanned and unrehearsed — a quick moment in the wake of the horrific tragedy,” Franklin told me. “A spontaneous act that lacked any sense of performance, occurring mere hours after the country had come under a direct attack.”

I asked Franklin about the immediate comparisons to Rosenthal’s photo. “The raising of the flag served as a powerful symbol of solidarity and strength during a time of crisis, much like Rosenthal’s,” Franklin responded. “The power of these two images rests within the emotions and feelings people derive from them.”

I’ve always admired Franklin’s photo. I lived in New York on 9/11 and made some pictures that morning, but didn’t have the chops or the wherewithal to get beyond the police lines after the towers fell. Franklin was robbed of the Pulitzer Prize, which went to a group of photographers from The New York Times.

But even cooler, like Rosenthal’s Raising the Flag on Iwo Jima, Franklin’s Raising the Flag at Ground Zero was made into a stamp.

In 2003, Franklin met Rosenthal at the Eddie Adams Workshop and presented him with a print. Rich Gigli, Franklin’s photo editor at The Record, captured the moment…

We all want our Raising the Flag on Iwo Jima — that one enduring photo that’ll be remembered long after we’re gone. After seeing Rosenthal’s photo, Soviet Red Army photographer Yevgeny Khaldei vowed to make one of his own. During the fall of Berlin on May 2, 1945, he got his chance.

Khaldei was carrying a huge Soviet flag made from stolen borrowed red tablecloths, sewn together by a family friend in Moscow, a tailor named Israil Kishitser. Khaldei enlisted a few soldiers, and hustled to the roof of the besieged Reichstag building — flag and camera in hand.

“This is what I was waiting for, for fourteen-hundred days,” Khaldei said. “It was scary, but I was euphoric so I didn’t notice.”5

Unlike Rosenthal, Khaldei meticulously staged his Raising a Flag over the Reichstag, running an entire roll of film through his Leica III recording the flag raising from all angles. Multiple versions are kicking around the internet but my favorite, by far, is the one above. Notice the tiny figure mid-stepping towards the Reichstag at the bottom of the frame, the perfect angle of the homemade flag, and the soldier’s head tilt.

Khaldei admitted, shamelessly, that he added the smoke in the sky along with a little hand of God. When asked about it, he’d often reply: “It’s a good photo. I made it. Auf wiedersehen.”

This near-frame is close, but the angle of the flag raiser’s face isn’t ideal, and the Soviet sickle and hammer are obscured.

Khaldei worked the hell out of it, even going vertical for a few. Notice how that Mercedes slowly moves through the frame — and the lack of heavy, black smoke.

An eagle-eyed TASS editor noticed one of the soldiers was wearing two watches — a subtle sign of looting — and demanded Khaldei get rid of it. “Alright, you want it off, I’ll take it off,” Khaldei snapped back. “I took a pin and scratched the watch off the right wrist.” Old school Photoshop at its best.

In 1995, Rosenthal and Khaldei were honored during the Visa pour l’Image photojournalism festival in Perpignan, France. During the ceremony, Khaldei referred to their iconic photos as The Revenge of Two Jews.6 Their meeting was immortalized in this anonymous photo.

Going down the rabbit hole of photos that are elevated, and in many defined, by flags made me think of Mustafa Hassona’s David-esque moment from a 2018 protest in Gaza.

The symbolism in Hassona’s photo is plain as day, social media gold. “I feel proud I was able to show the world some of the suffering that the people of Gaza are experiencing,” Hassona messaged me.

His instantly-viral, near-biblical photo drew apt comparisons to Eugène Delacroix's Liberty Leading the People.

I also thought about this subtle, but moving, anti-flag photo by Rachel Posner. During Hanukkah in 1931, Posner, the wife of a Rabbi, photographed her family’s menorah in the window of their home in Kiel, Germany. A Nazi flag draped on a building ominously looms in the background.

It’s an intimate, personal photo that still resonates as a symbol of defiance and inspiration. So much so that Posner’s great-grandson, Raziel Gilo, brought a copy of the photo, and the family Menorah, to an Israeli base on the border of Gaza during Hanukkah last year.

There was a deluge of flag photos during the recent campus protests over the war in Gaza. Palestinian, Israeli, and American flags were everywhere, front and center, attracting photographers — and photo editors — like moths to a flame. Mark Peterson’s photos, published by The New York Times Magazine, are a great example.

Another: on April 30, 2024, Parker Ali, a student at the University of North Carolina, took this photo of a group of students propping up an American flag during a counter-protest.

Obviously, it’s a stretch to compare Ali’s photo with Rosenthal’s, but it briefly served a similar purpose for a specific audience. When a photo aligns with someone’s politics, intended or not, people tend to rally around it. A GoFundMe hijacked Ali’s photo and raised over a half a million dollars for the “Frat Bros” to “Throw ‘em a Rager.” It’s no war bond, but still. It was a galvanizing photo of a flag that gave people meaning.

An alternate angle of the “Frat Bros,” taken by Daily Tar Heel photographer Heather Diehl, offers a bit more perspective and an Israeli flag. The spraying water is a nice touch.

No photographer is immune to the gravitational pull of photographing flags. Once you look for them, they’re all you’ll see. Even the greats will pick some of that low-hanging fruit from time to time. The late, great, Robert Frank, who used photos of the American flag as informal chapter breaks in The Americans, put it perfectly: “it is a good-looking flag and you can’t go wrong with it.”

Thomas Farragher, “Image of an Era: Reluctant Symbol Ted Landsmark at Peace with His Assailant and Boston,” Boston Globe, April 1, 2001.

Vicki Goldberg, ed., Photography in Print: Writings from 1816 to the Present (New York: Simon and Schuster, 1981), 386.

Joe Rosenthal, “The Picture That Will Live Forever,” Collier’s Magazine, February 18, 1955, 65.

Ibid, 67.

Yevgeny Khaldei, Witness to History: The Photographs of Yevgeny Khaldei (New York: Aperture, 1997), 11.

Ibid, 10.

I will just offer that my brain wants the iconic Iwo Jima flag raising photo to be a statue - I have to bully my brain into believing it’s an image of flesh and blood humans in action, rather than a photo of a statue (of a photo), so solidified is that image in my American cultural consciousness

Wonderful article - great read. And well researched, as always Patrick. For the most part though this is a very American leaning view, but perhaps understandable given the way the US flag's place in culture, politics and throughout any American's life. Although not as pervasive or political, other flag photos have had huge impacts on other counties as well.

Two years ago Canada was roilled by protests across the country by a loose conderation of right wingers and anti-vaxxers, culminating in weeks of a noisy occupation of Parliament Hill in Ottawa. It was the equivalent in its way of the Jan 6 events in Washington 2 years before that, and was the most visual evidence of the polarization going on in Canada. Although most of the country found it annoying and just wished the "truckers" would leave their capitol, nothing happens until this photograph of the desecration of a statue of one of this country's most revered people was desecrated by the protesters: https://www.reddit.com/r/pics/comments/sfs7ll/canadian_icon_terry_foxs_statue_defaced_during/

I believe the VP photographer was Adrian Wyld. Once this was published, the rise turned against the occupation in a huge way and the RCMP finally decided to end it by towing away tricks and moving people away from Parliament.