In the winter of 1938, Walker Evans tucked his painted-black Contax discreetly under his overcoat and descended into the New York City subway, searching for something real, hunting for what he called “true portraiture.”1

Evans had grown angry, “irritated by the icy, alluring commercial portraits of Cecil Beaton, Yousuf Karsh, and Edward Steichen,”2 and decided to secretly photograph unsuspecting subway riders. “The guard is down and the mask is off: even more than when in lone bedrooms (where there are mirrors), people’s faces are in naked repose down in the subway,” Evans famously wrote.3

Alongside his accomplice, Helen Levitt, Evans collected people with his eyes, making roughly 600 photos without ever peering into the viewfinder, triggering the shutter with a cable release snuck down his sleeve into his right hand.

Evans’ brilliant, unsentimental photo of a mother and child (above) is a direct reference to his inspiration for the series: Honoré Daumier’s painting, The Third-Class Carriage.

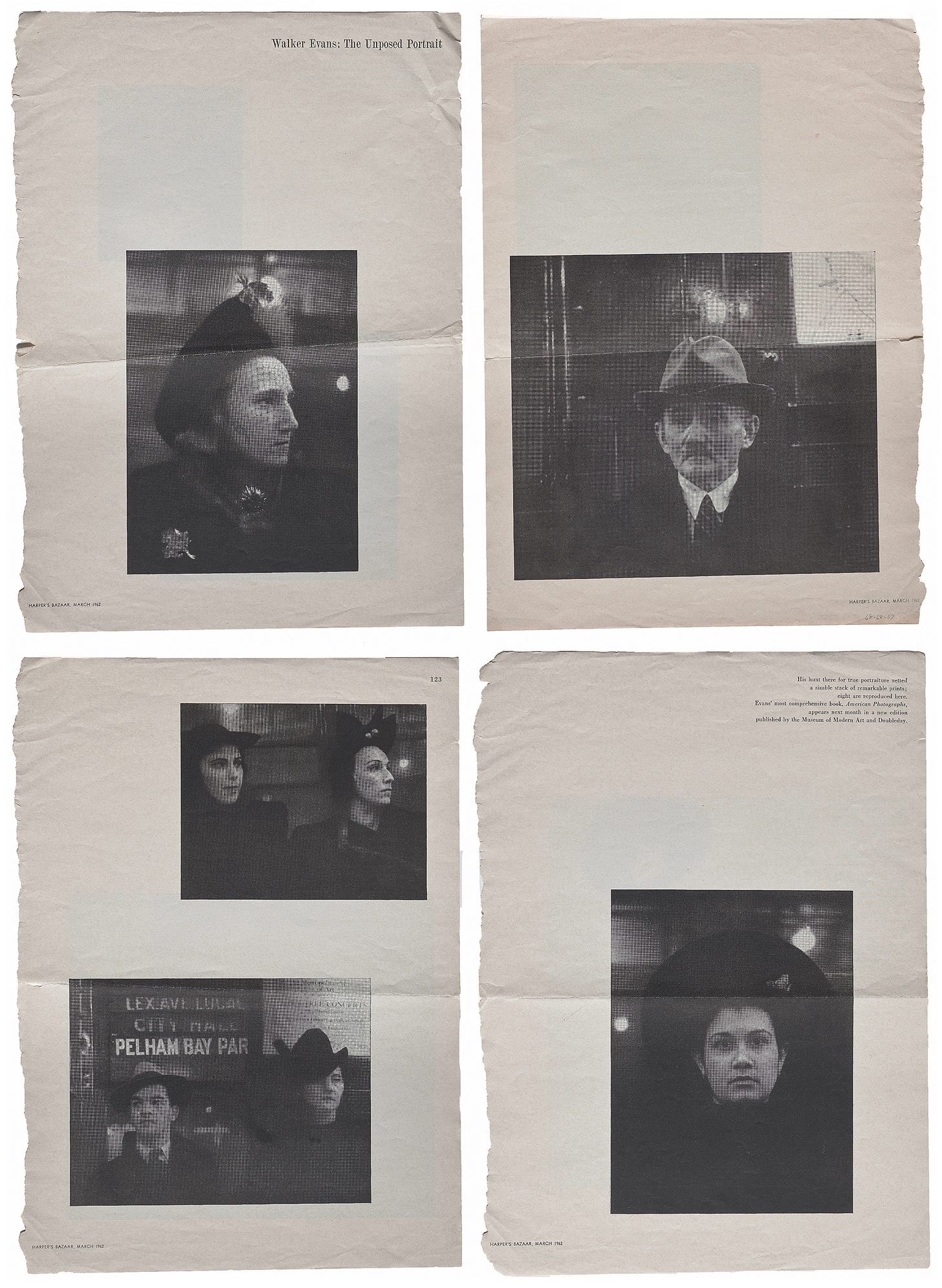

Evans, the “penitent spy and an apologetic voyeur,”4 sat on the photos until 1962, when famed art director Marvin Israel published a small selection in Harper’s Bazaar.

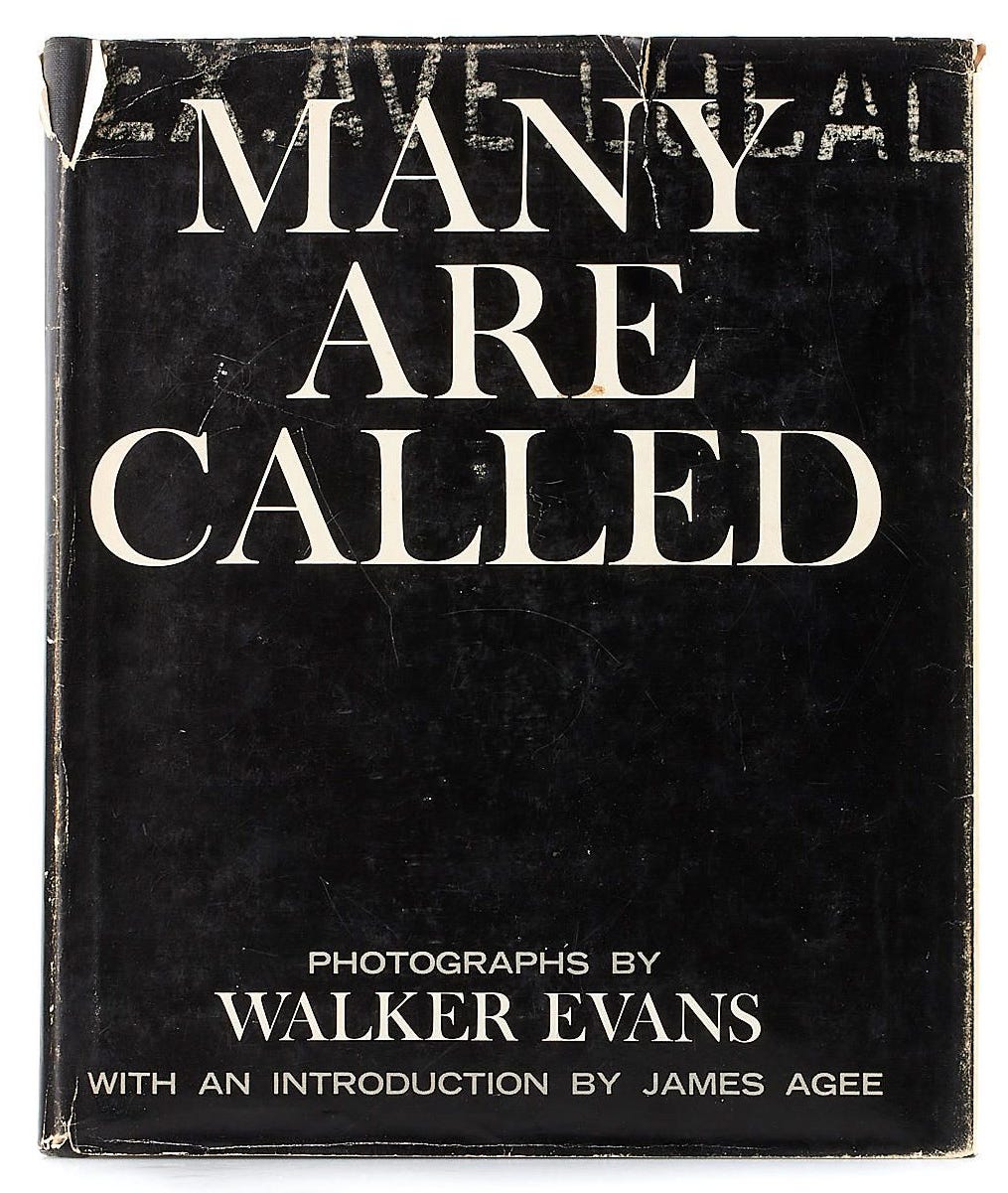

In 1966, after Evans’ self-described invasion of privacy had been “carefully softened and partially mitigated by a planned passage of time,” his book was finally published.5 Many Are Called is a masterpiece.

A copy of the book, along with Evans’ Contax II and Sonnar 50/1.5 lens, fetched $20,000 at auction in 2022. The matte-black paint used to conceal the camera has mostly been chipped away.

I wonder how Evans’ subway photos — in particular his image of the mother and child — would be received today? Would the work have the same profound impact and meaning had Evans sought permission of his subjects? I think not.

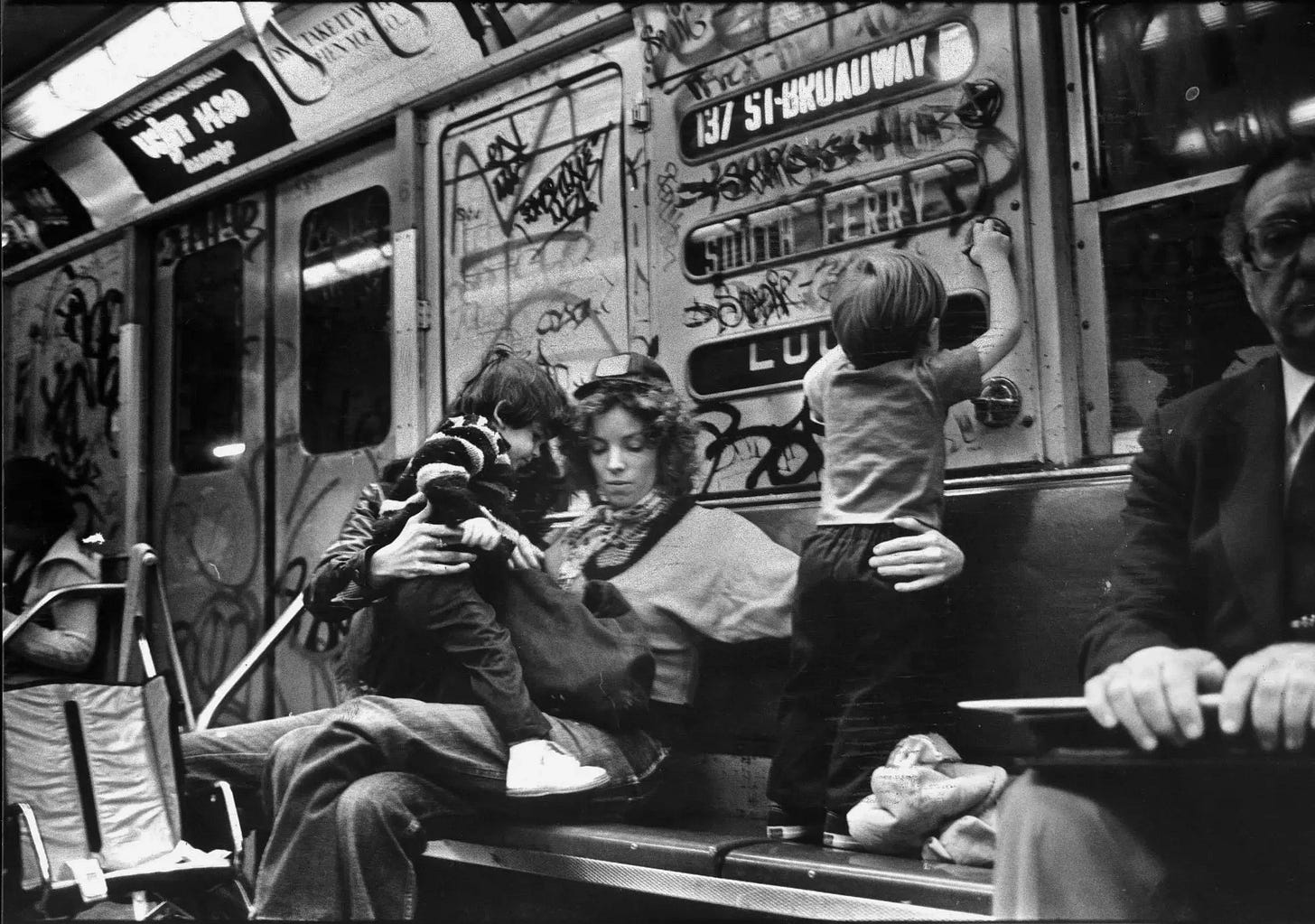

Consider this 1979 photo by Neal Boenzi, photographer for The New York Times. It’s an intriguing echo of Evans’ photo, from a vastly different era.

Unfortunately, I never had the opportunity to work with Boenzi, he’d retired long before I landed at the Times in 2004, but I was a fan of his work — newsy, wild and gritty, like the crazy photo he shot of a woman being attacked by a lion. Boenzi didn’t ask for permission to make that photo.

Likewise, Paul Kessel didn’t ask for permission when capturing this unguarded, lyrical moment of a mother and her children on the Q Train in 2019. A truly modern version of Evans’ photo.

Although Kessel’s Leica wasn’t hidden in his overcoat like Evans’ Contax, he wasn’t looking through the viewfinder either — it was resting in his lap when the woman and her kids fortuitously sat down across from him. “I looked up and there they were, in a perfect position,” Kessel explained to me. He guessed the distance and started shooting. “Somehow it came out ok,” he added.

The photo went viral and won several awards, eliciting both praise and criticism — largely because Kessel didn’t get her consent. But what if he’d taken the photo with his camera at his eye (something I’d label “implied consent”)? Or simply asked her for permission? It might have quelled some of the criticism but the magic would’ve been gone.

Despite its virality, the woman in the photo has never come forward or been identified. I asked Kessel what he’d say to her if given the chance. “I hope you like the photo,” he responded. “I would like to give you a framed print.”

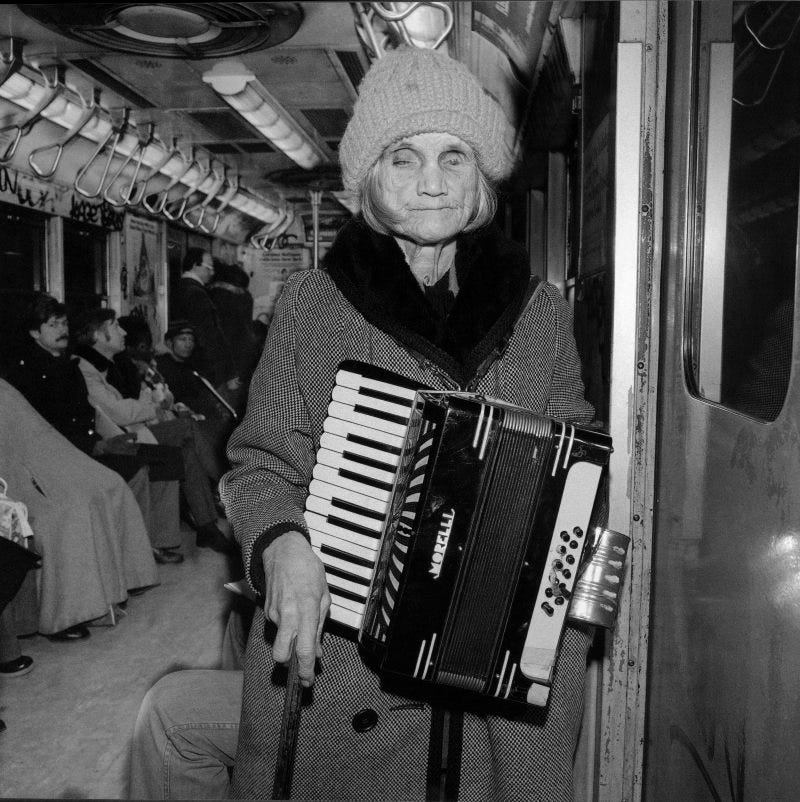

The last photo in Many Are Called is an outlier, the only image that wasn’t taken from across a seated passenger. But it’s one of the most dynamic and speaks directly to this notion of consent.

Like Kessel, or any photographer shooting from the hip, Evans guessed on the focus and made several frames of this scene — many are soft.

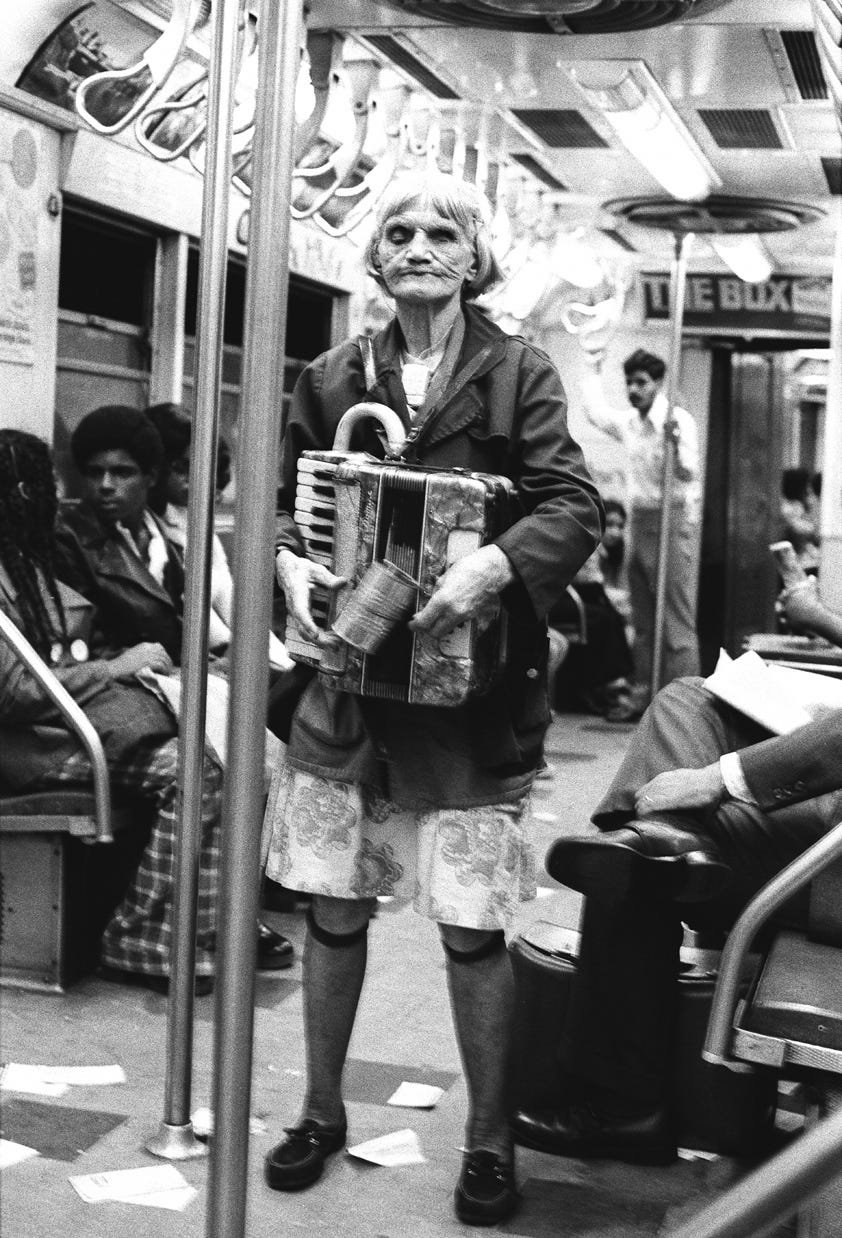

Evans’ series of the blind accordionist reminded me of this 1980 photo by Bruce Davidson.

Davidson’s extraordinary book, Subway, is a revealing companion, a gritty counterpoint to Many Are Called. Unlike Evans, Davidson worked openly and with a strobe, often asking for permission of his subjects.

Turns out that Davidson had photographed this same woman years before, in 1958, while documenting the life of composer Leonard Bernstein.

Remarkably, in 1969, LIFE magazine’s Ralph Crane photographed the same accordionist. Crane’s photo is even more evocative of Evans’.

A few years later, Leland Bobbé, known for his photography of New York City in the 70’s, also documented the musician busking in the subway.

And another one…in January of 1979, Meryl Meisler photographed “Accordion Lady in the Subway.” Meisler, like Davidson, used a strobe, yet her approach exudes a sense of dignity.

“Walker Evans was my inspiration when I started photographing NYC subways,” Meisler wrote to me. “In my mind, I was Walker Evans.”

Evans’ words are worth repeating, and remembering: “Stare, pry, listen, eavesdrop. Die knowing something. You are not here long.”6

Walker Evans, “Walker Evans: The Unposed Portrait,” Harper’s Bazaar (March, 1962): 125.

Walker Evans, Walker Evans at Work (New York: Harper & Row, Publishers, Inc., 1982). 108.

Belinda Rathbone, Walker Evans: A Biography (New York: Houghton Mifflin Company, 1995). 171.

Walker Evans, Walker Evans at Work (New York: Harper & Row Publishers, Inc., 1982), 160.

Ibid, 160.

Belinda Rathbone, Walker Evans: A Biography (New York: Houghton Mifflin Company, 1995). 28.

Geoff Dyer has a fascinating section in The Ongoing Moment about photographers obsession with blind people. That is, with those who can't object to being photographed. It includes some of those Subway blind people.

The conclusion I came to is that you should treat (photograph) as you would want to be treated (photographed). There has to be respect and I think those pictures of mothers and children are respectful, even if they objected.

https://neilscott.substack.com/p/the-ethics-of-street-photography

A fellow photographer coined the phrase ‘the anti-pose’ for the moment before a person is aware of you taking their photo. That rested, unconcerned expression can not be authentically produced when the subject is aware.