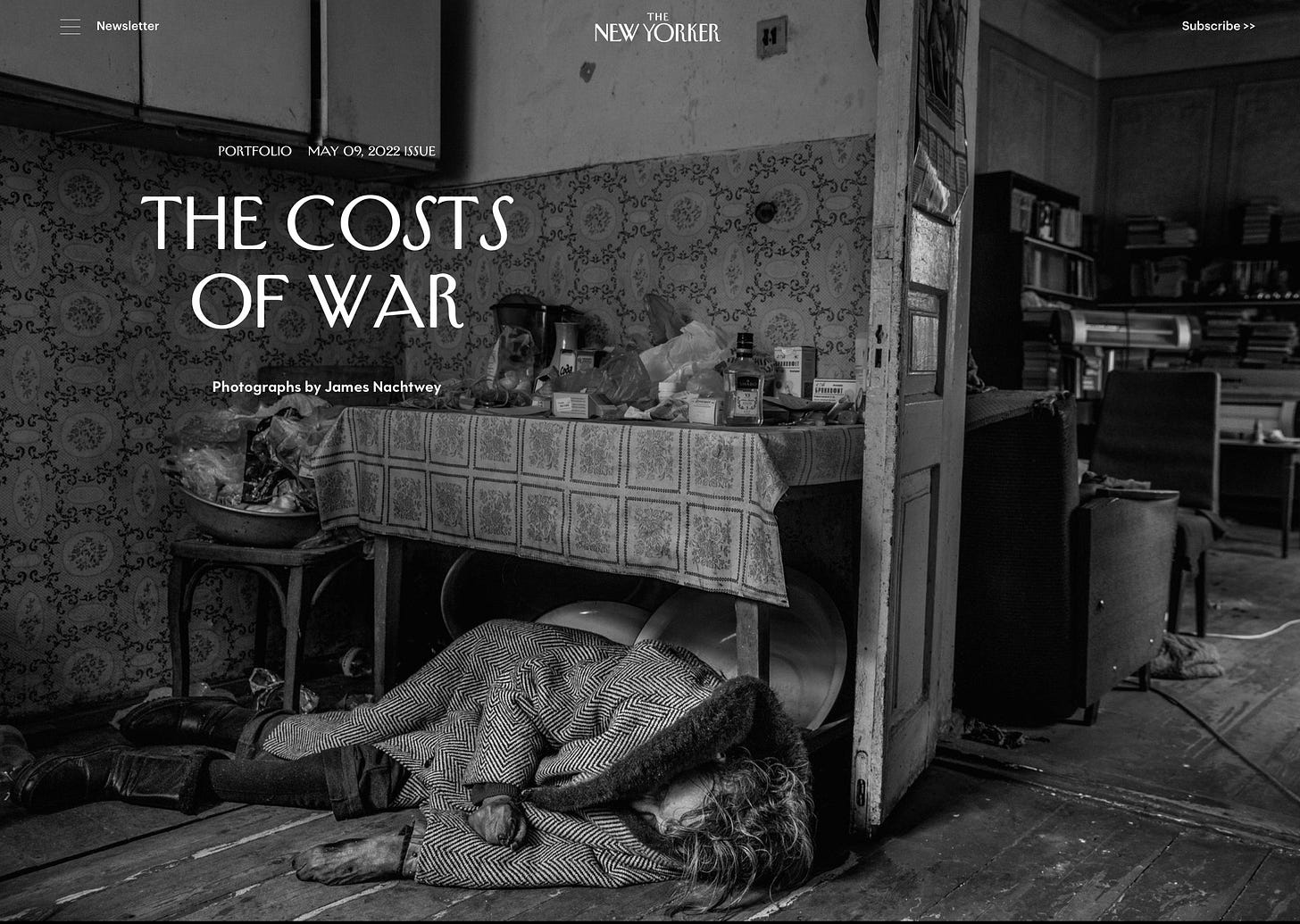

The Woman in the Kitchen

A casualty of the war in Ukraine documented by seven photographers, each with distinction.

Warning: This story contains graphic photographs of war. Viewer discretion is advised.

Of all of the coverage of the war in Ukraine, the horrific photographs from the massacre in Bucha remain seared into our collective consciousness. One scene in particular has stuck with me. Having spent the greater part of my career looking at too many photos of death and misery and war, these, of a dead woman lying in her kitchen, are among the saddest.

Her name was Nina. It’s unclear how she died. The New York Times reported that Nina’s sister, Lyudmyla, who was discovered murdered in the doorway of her home, was killed on March 5th. These photos were taken April 5th and 6th.

“There were so many bodies in Bucha, sometimes you'd just look behind a fence and see a dead body in the park or on the street.” Ukrainian photographer Maxim Dondyuk told me.

Photographers often travel in groups in war zones for safety and logistical purposes and frequently share info with each other. That day, Dondyuk, on assignment for Der Spiegel, was working alongside veteran war photographer James Nachtwey.

“We were told about the location by Daniel (Berehulak).” Dondyuk said. “We, in turn, also shared the location with other photographers afterward. We were all working for different media at the time and understood that the situation had to be shared as widely as possible.

“Her sister was lying murdered at the front door. The door was slightly opened and she was face down. The little dog was in the yard, barking very noisily, and wouldn't let anyone in the house. We often carry canned food for stray animals in the car, and this distracted the dog and allowed James and me to go inside. Judging by the number of empty canned goods in the yard, we weren't the first.”

I asked Dondyuk about the slightly-open stove in the photo he made of Nina. “I wanted to show the ordinariness of life in which death suddenly arrives,” he responded. “It was important for me to convey the atmosphere of the room, how the woman lived, how it was, the chair, the books, and the wallpaper. I wanted to shoot an ordinary scene in which the body of the murdered human being is not immediately conspicuous.”

Der Spiegel did not publish Dondyuk’s photo, but TIME did.

Daniel Berehulak, who was working for The New York Times, chose a slightly different angle, including the view into the next room. The door adds another layer of symbolism to the photo, a greater sense of place, but unclear that it’s a kitchen. The Times published Berehulak’s photo online and in print the following day.

There’s not a right or a wrong way to frame something this horrific. I’m pointing out these details and nuances to applaud each individual photographer’s specific vision. All of these choices - what to include, what not, from what angle, black and white or color, tonality, etc. are important and, with the ubiquitousness of photography these days, make all the difference.

Azerbaijani freelance photographer Aziz Karimov captured the most wide-angle version of the scene. I typically find most photos shot wider than 28mm distracting, but there’s a strong, sad, sense of solitude here. Karimov’s photograph of Nina, moved by the AP, via Sipa, via SOPA Images, was published in the Yeni Avaz newspaper in Baku, Azerbaijan.

Brazilian Associated Press photographer Felipe Dana has been covering Ukraine for months, creating an indelible body of work. The AP moved two versions - one with the dog Dondyuk referred to, and another without. Each have their merits, but I applaud the inclusion of the stove and the door, with what appears to be a religious calendar tacked to it.

“I saw a lot of things I wish never happened, horror scenes I can only hope will never repeat,” Dana recalled to the AP.

Oleg Pereverzev, a Ukrainian photographer working for Reuters, composed his version through the kitchen window. The empty bowl and spoon add another layer to the image, humanizing an otherwise dehumanizing scene. Pereverzev’s photo was included in Reuters’ Pictures of the Year.

Narciso Contreras, freelancing for Anadolu Images, was traveling only with his driver that day. He told me the massacre was one of the most shocking subjects he’s documented.

“There were horrendous scenes of bodies found scattered in basements, streets, yards and houses many with visible signs of torture and gunshots,” Contreras said.

Contreras said the he included the stove in his composition to give a “sense of intimacy disrupted.”

“This woman was killed in her kitchen,” he said. “The sense of everything is broken.”

Contreras’ photo was published by multiple publications, including The Intercept. (Note to the editors: photographers have names, not just agencies. Please try to use them when possible.)

Color is absent in James Nachtwey’s photo of Nina. His use of black and white frees all distractions from color, giving the scene weight and magnitude. Nachtwey, on assignment for The New Yorker, meticulously composed the photo to include the door with a glint of light casting a symbolic highlight. It could have been made 50 years ago.

(I must admit I was shocked not only at the photo and its play, but seeing Nachtwey’s photo in The New Yorker, and not TIME.)

The New Yorker published Nachtwey’s photo as the lead in his “Portfolio” from Bucha. Bravo to The New Yorker’s Andrew Katz, Nachtwey’s editor, who shared the print layouts on his Instagram account.

The display online is equally powerful. Nachtwey told The New Yorker: “The barbarity and the senselessness of the Russian onslaught are hard to believe even as I witness them with my own eyes.”

When I saw Nachtwey’s photo of Nina in The New Yorker, I was reminded of another photo he made in Mostar, Bosnia, almost 30 years earlier.

His description of that image could also characterize the photo of Nina.

“Most wars today are not waged on isolated battlefields, but within civilian populations,” Nachtwey told TIME. “The battle for Mostar was fought from house to house, room to room, neighbor against neighbor. A bedroom, the place where people sleep and dream and share intimacy, where life itself is conceived, had become the frontline in a brutal civil war.”

But instead of a bedroom, it was a kitchen.

Can there be too many angles of suffering? Absolutely not. I’d argue that there are not enough, and certainly not enough being published for the world to see - and remember.

Well done. Educating.