The Toppling of Saddam's Statue: Act I

Dozens of photographers capture a controversial moment that symbolized victory for some, imperialism for others.

This is the first installment in a three-part series.

The events surrounding the toppling of Saddam Hussein’s statue on April 9, 2003, have been written about extensively and thoroughly dissected, most notably by Peter Maass in The New Yorker. Dozens of photographers were there that day and documented the events, which Maass aptly described as “an illusional intermission between invasion and insurgency.”

But before Saddam’s statue fell, a Marine by the name of Corporal Edward Chin draped an American flag over its face. Chaos ensued. A minute and a half later, Chin took it down.

One of the most widely-published photos of that moment was taken by Associated Press photographer Laurent Rebours (see above). Direct and to the point. Tight and bright.

The Washington Post published Rebours’ photo as part of a sequence.

The New York Post was far less subtle. The caption reads: “Cpl. Edward Chin of Brooklyn turns Old Glory into a burqa for the Butcher yesterday before this Baghdad statue of Saddam was toppled.”

The New York Times, The Los Angeles Times, and The Wall Street Journal did not publish an image of the flag. Others did.

Another AP photographer, Jerome Delay, made this layered, concentric image. The hands of the statue, the soldier, and of the Iraqi man reaching towards the sky, echo each other nicely. The slight tilt helps fill the frame entirely.

Delay’s photo was also widely-published, most recently in USA Today as part of a 20th anniversary package.

Alexandra Boulat, on assignment for National Geographic, has a similar frame to Delay’s, but vertical, capturing the full scale of the statue. The expressions on the soldier at left and the Iraqi man are compelling. Boulat’s work from Iraq is stunning — more on that in the second part of this series.

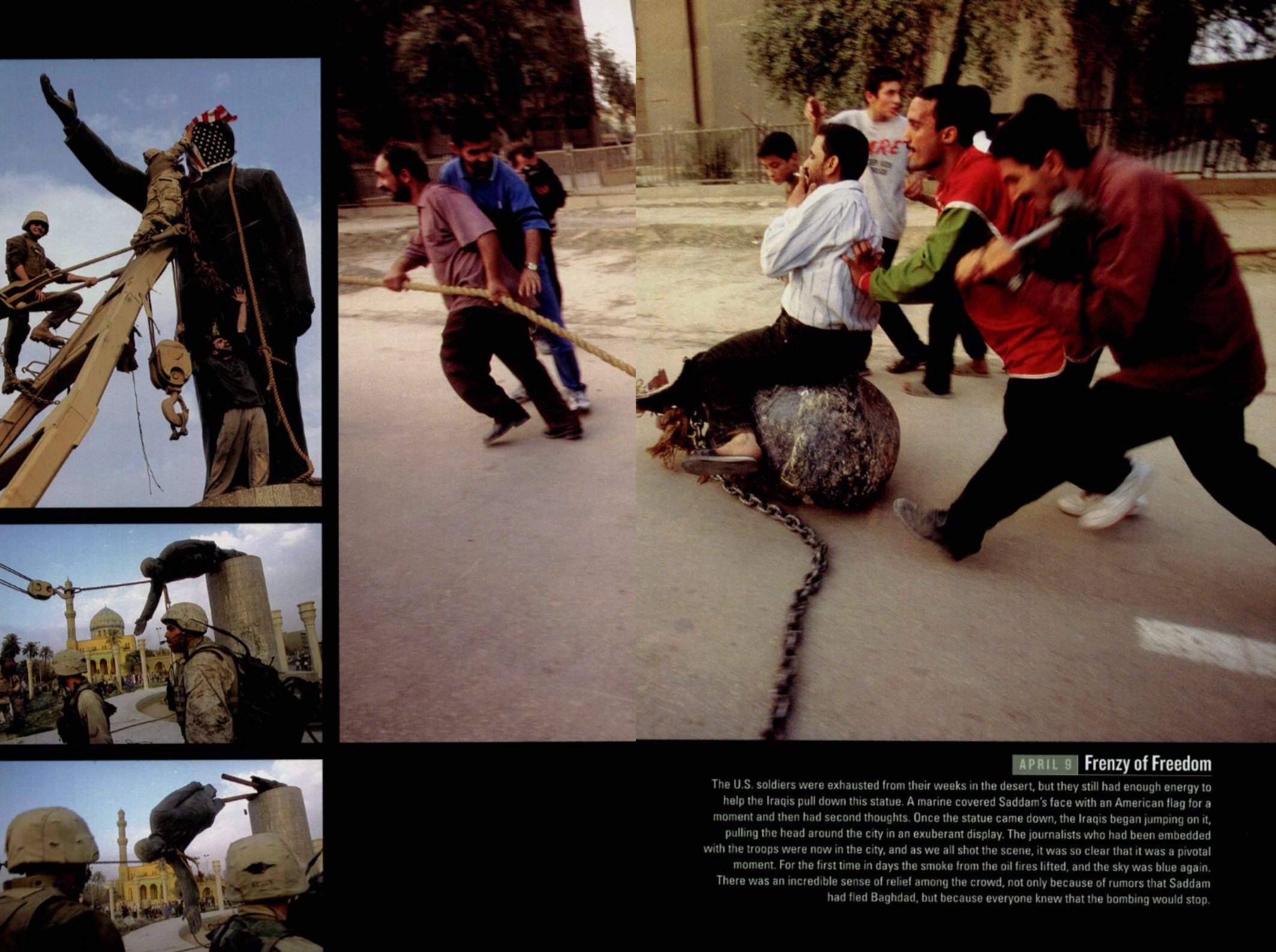

National Geographic published a sequence of Boulat’s in the September 2003 issue. “A Marine covered Saddam’s face with an American flag for a moment and then had second thoughts,” she wrote.

Kael Alford’s version is slightly wider — the Iraqi man’s expression appears more doubtful than jubilant. The chain used by the Marines to pull down the statue can also be seen. Alford’s work from Iraq is part of the must-have book, Unembedded: Four Independent Journalists on the War in Iraq.

Daily Mirror photographer Mike Moore shot this image just after the flag was removed. There’s added context of other soldiers at the base of the statue and a cheering Iraqi in the foreground.

But in print, the Daily Mirror published a different, tighter frame by Moore. “I was always more worried about being shot at by the Americans than I was by the Iraqis,” Moore said in an interview after the war.

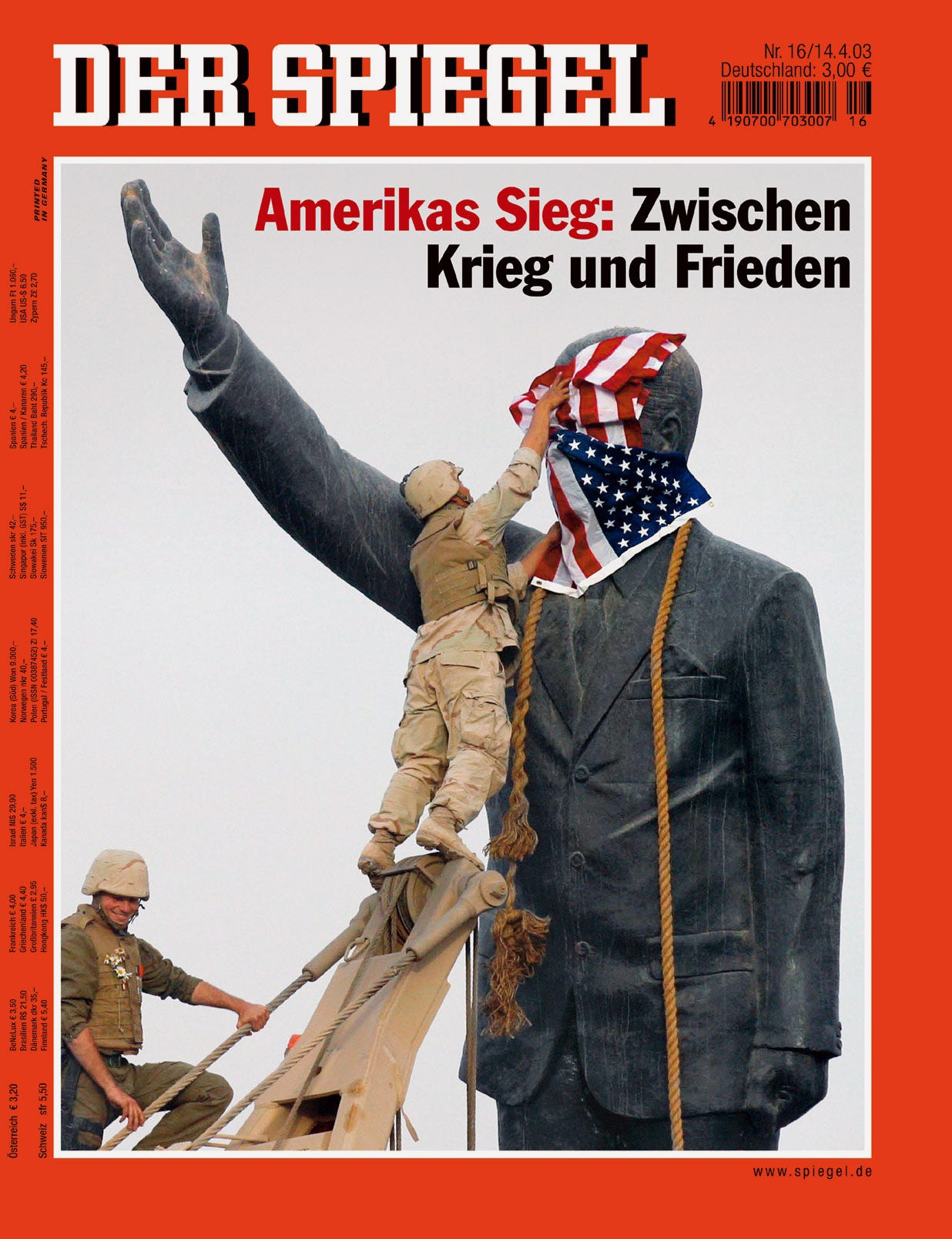

Christophe Calais’ photo landed on the cover of Der Spiegel with the headline: “America's Victory: Between War and Peace.” The expression of the soldier on the left is telling.

This photo by Ron Haviv was made a split-second after Alexandra Boulat’s (notice the position and angle of the Iraqi man’s hand, mirroring the statue). Haviv wrote about this image in TIME on the 10-year-anniversary of the war, expressing, “For many, this changed the image of liberation to one of occupation.”

Haviv covered the war for Newsweek, which published two photos of the toppling in the April 21, 2003 issue (Haviv’s on the left and Laurent Rebours’ at right).

After the flag came down, it ended up in the hands of the Iraqi man on the statue. Agence France-Presse’s Ramzi Haidar captured the moment the flag began to wave. Haidar was just featured in FoV for his photo of “Shock and Awe” on the cover of TIME. The composition is formal, in thirds, the statue balanced by the tower at left. The flag is perfect but the rope dissects the Iraqi man.

TIME magazine photographer James Nachtwey made a similar image, but wider, introducing another Marine with an outstretched hand on the left. The rope lands to the right of the Iraqi man, splitting him and the waving flag. Damage can be seen at the base of the statue, created by a sledgehammer given to the crowd by the Marines.

Reuters photographer Goran Tomasevic made a much tighter (and brighter) version, filled with detail but lacking much-needed context.

Tomasevic also shot one of the most iconic photos from that day of the statue coming down. Yet, El Universal and O Estado de S. Paulo published his flag photo.

One of the more interesting angles was captured by Getty Images’ Wathiq Khuzaie. I like the subtlety of the shrouded head and the added context of the tank. Bloomberg published this image in 2021. I’d never seen it before, but it continues to grow on me.

Other versions were shot by Jerome Sessini, Gary Knight, Gilles Bassignac, Kuni Takahashi, Olivier Jobard, Patrick Baz, and Albert Facelly.

This was a complex situation for photographers. Would the Marines have helped pulled down the statue if journalists hadn’t been there? Does taking pictures further perpetuate the events unfolding? Would the Iraqis have celebrated as passionately if cameras weren’t present, or even celebrated at all?

Do you stop taking photos or keep going, working the best frame you can make? Tough call, but I feel that this event had to be fully documented — photo editors can sort it out later. Some did, some didn’t.

As Gary Knight recalled to The New York Times in 2013, “I saw this for what it was — this wasn’t Iwo Jima.”