The Soldier in the Snow

A dark journey down the rabbit hole of war photos, blanketed in snow.

Warning: This story contains graphic photographs of war. Viewer discretion is advised.

Private First Class Tony Vaccaro, carrying an M-1 rifle and an Argus C3 brick camera, photographed this scene January 11, 1945, during the Battle of the Bulge. At first glance, it looks like a painting - spartan and stark, the composition as cold as the day.

“I saw the soldier that was lying down so peacefully, so beautiful as if an artist had drawn it.” Vaccaro recollected in the excellent 2016 documentary Underfire: The Untold Story of Pfc. Tony Vaccaro. “Death, that is beautiful. It’s a contradiction. You want the ugliest aspect of mankind, death, to be beautiful. Otherwise it can not be a monument.”

Vaccaro died in 2022 at the age of 100. The photo, titled “White Death, Requiem for a Dead Soldier,” was published alongside Vaccaro’s obit in The New York Times.

It reminded me of this photo from Ukraine by Tyler Hicks, of a dead Russian soldier covered in snow near a bombed-out tank.

There’s a strong sense of place and scale in Hicks’ photo, far less abstract than Vaccaro’s. It ran on Page One of The New York Times under a six-column headline - bleak and bold.

Vaccaro’s and Hicks’ photos prompted this journey, starting with the Battle of the Bulge.

Dubbed the “the greatest American battle of the war” by Winston Churchill, tens of thousands of soldiers died during the Battle of the Bulge, which was fought in the frigid Belgian winter at the end of 1944 and beginning of 1945.

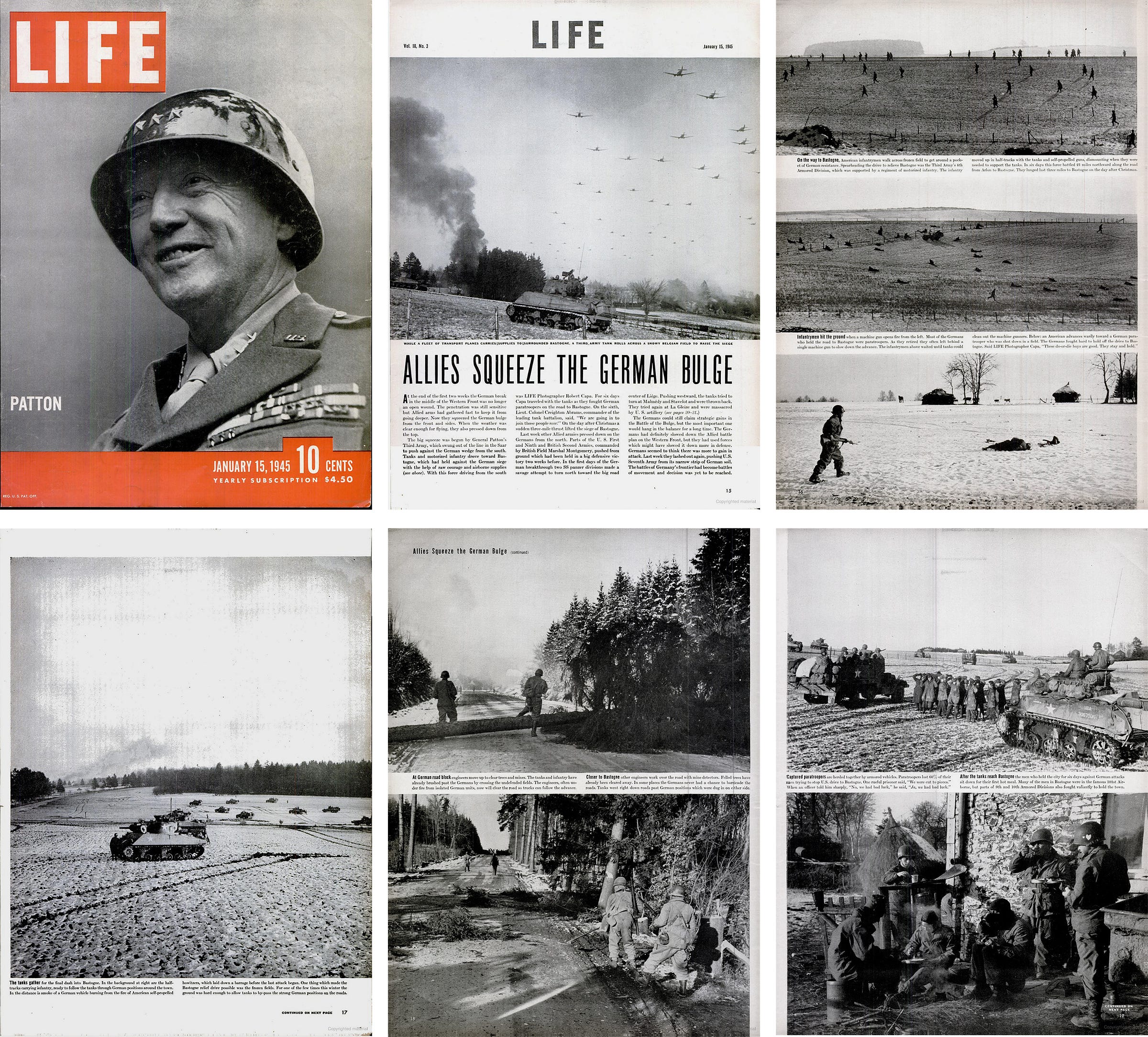

The legendary war photographer Robert Capa documented the Battle of the Bulge for LIFE magazine. His photos appeared in the January 15, 1945 issue.

Though Capa’s riveting photo of a US Soldier with a German prisoner of war didn’t make the edit; the subtlety and simplicity of the frame may have been lost on the LIFE “Picture Bureau” editors at the time.

John Florea also photographed the Battle of the Bulge for LIFE magazine and captured this image of a fallen German soldier. This photo also was not published.

Florea, who after the war became a television director (including episodes of CHiPs and The Dukes of Hazzard), made the definitive image from the Malmedy Massacre during the Battle of the Bulge, for which he’s often uncredited.

Unfortunately, two of the most powerful images from the Battle of the Bulge are uncredited. The caption for this image in the Associated Press archive reads: “Seriously injured GI lays in the snow in Belgium, Dec. 1944.” It’s safe to assume that was taken by a member of the U.S. Army Signal Corps.

This haunting photo of a dead German soldier in a foxhole is also uncredited. It’s from the Hulton-Deutsch Collection (acquired by Getty Images in 1996), so it likely originated from the photographic archive of Picture Post (Britain’s LIFE magazine).

The caption in the Getty archive reads: “A Dead Nazi officer in a snow filled foxhole. He commanded a German 88mm piece which was knocked out, killing him and the entire crew. We came on this German officer right outside Mabompre, Belgium. He didn't freeze, he stopped one of our shells. The live ones must have left in a hurry. They had a habit of looking after their dead but I guess we were pushing them too hard.”

The quote is unattributed.

Russian photographer Mark Markov-Grinberg captured this photo of a frozen German soldier during the Battle of Moscow in 1942. Markov-Grinberg fought as a soldier in the Russian Army before becoming a photographer for Slovo Boitsa, a military newspaper. The missing gloves are a grim detail.

Rista Marjanović, Serbia’s first war photographer, made this photo of a dead Serbian soldier during The Great Retreat on the Eastern Front of World War I 1915. The photo is credited to “Serbian official photographer” in the International War Museum.

In 1890, George Trager was one of two photographers to document the Wounded Knee Massacre at the Pine Ridge Indian Reservation in South Dakota. Trager photographed the body of Chief Spotted Elk, who, along with more than 150 others in the Lakota tribe, were killed by the U.S. Army.

But few photos exude the cruelty of war more than this, taken by Russian photographer Mikhail Savin. The details are unclear. Some sources claim Savin made this photo during The Winter War in 1939 and that the frozen soldier is Russian, propped up by the Finnish soldiers as an act of psychological warfare.

Others, including myself, believe the photo is from the Battle of Stalingrad in 1942 and a dead German soldier is pictured, propped up by the Russians for the same cruel reason. During that time Savin was working for The Krasnoarmeyskaya Pravda (Russian military newspaper), which gives this theory some weight.

Years after the war Savin was asked what memories of his remained. “Not the way I crawled under machine-gun bursts to make a picture for the newspaper, or when I went on the attack with soldiers,” he recalled. “It all merged into something single, terrible, bloody, which I don’t even want to remember. Life there, your personal life, often seemed like a miracle, an incredibly generous gift of fate.”

Vacarro titled his image "White Death, Pvt. Henry Irving Tannebaum Ottre, Belgium 1945, 1945", making it, for me, very concrete. Not an abstract death, but the death of one, specific, knowable, remembered young man.