The Greatest Protest Photos of All Time

On June 5, 1989, six photographers captured a lone protester facing down a column of Chinese tanks near Tiananmen Square. 'Tank Man' was born.

Few photographs are more recognizable, more evocative, or more symbolic. “Tank Man” not only embodies the historic Tiananmen Square protests, but also serves as symbol of defiance against oppression everywhere.

The most widely-published version was taken by Jeff Widener for the Associated Press.

“Sometime in the morning of June 5, 1989, I stumbled out of the Jianguo Hotel in Beijing and navigated my way past burned out buses and smashed bicycles to The Associated Press office,” Widener told me in 2009. “I was sick as a dog with the flu and suffering from a severe concussion. A stray rock had struck my face while photographing a burning armored car during the Tiananmen uprising. The Nikon F3 Titanium camera had had absorbed the shock and thus saved my life.”

I was really scared and very spaced out from the injury and I had to find the courage to make that long bicycle ride to the Beijing Hotel, which had the best vantage point. In the end, I managed to smuggle my camera gear into the Beijing Hotel and past security police, thanks to a young college kid named Kirk. Two decades later, I still have not been able to locate him and express my gratitude. For without his help, the world would have lost a memorable image.”

As I shot pictures out the sixth floor of the Beijing Hotel balcony, I was going through film pretty fast. Tanks crashed through burned out buses. Dead and wounded were peddled on little carts. I asked Kirk to help find me some more film. He returned an hour later with one roll of Fuji 100 ASA color negative film. Only one tourist could be found in the deserted lobby. I normally shoot 800 ASA. This would be a critical factor later on.”

I loaded the single roll of film in a Nikon FE2 camera body. It was small and had an auto-exposure meter. As I tried to sleep off the massive headache that pounded my head, I could hear the familiar sound of tanks in the distance. I jumped up. Kirk followed me to the window. In the distance was a huge column of tanks. It was a very impressive sight. Being the perfectionist that I am, I waited for the exact moment for the shot.”

Suddenly, some guy in a white shirt runs out in front and I said to Kirk, ‘Damn it — that guy’s going to screw up my composition.’ Kirk shouted, ‘They are going to kill him!’ I focused my Nikon 400/5.6 lens and waited for the instant he would be shot. But he was not.”

The image was way too far away. I looked back at the bed and could see my TC-301 teleconverter. That little lens adapter could double my picture. With it, I could have a stronger image but then I might lose it all together if he was gone when I returned.”

I dashed for the bed, ran back to the balcony and slapped the doubler on. I focused carefully and shot one…two…three frames until I noticed with a sinking feeling that my shutter speed was at a very low 30th-60th of a second. Any camera buff knows that a shutter speed that slow is impossible hand-held with an 800mm focal length. I was leaning out over a balcony and peeking around a corner. I faced the reality that the moment was lost.”

I had earlier accomplished my mission of photographing the occupied Tiananmen Square so I gave all my rolls of film to Kirk who smuggled it back to the AP office in his underwear. The long-haired college kid was wearing a dirty Rambo t-shirt, shorts and sandals. Security would never suspect him of being a journalist.”

Five hours later, without any film and exhausted, I called the AP bureau in Beijing. The photo editor, Mark Avery, asked, ‘Jeff, what shutter speed were you shooting?’ My heart sank. Mark said, ‘It was OK. We used it, but it wasn’t very sharp.’”

The next day I arrived at the office, where Liu Heung Shing jokingly said that I had ‘very bad messages from New York.’”

On the clipboard were message after message of congratulations from all over the world: ‘Congratulations. Widener’s tank man fronting all UK newspapers half page.’ ‘Tank man fronting all European papers.’ ‘Wish I was there, Horst Faas, London.’ ‘French newspaper Liberation wants exclusive interview with Jeff Widener.’ ‘Tank man fronting USA Today and International Herald Tribune.’ ‘Please contact Life magazine for tank man image.’ The response was overwhelming.”

“My unexpected 20th anniversary return to Beijing was filled with emotions. On one particular day, I recall walking down a very tranquil tree-lined boulevard by the American embassy. As I strolled through Beijing’s Ritan Park and sniffed that pleasant wood burning smell of Asia, I found it hard to imagine such hell took place on those streets two decades earlier.”

In 2012, I interviewed Widener again for TIME. “I was on the computer and that familiar ‘You’ve Got Mail’ rang out on AOL,” he recalled. “I could not believe who it was from. After 20 years, Kirk had found me because of the article in The New York Times.”

Widener was robbed of the Pulitzer Prize in Spot News Photography (he was named a finalist).

Charlie Cole was covering the protests in Beijing for Newsweek. Cole’s version of “Tank Man” is the tightest — simple, striking, and powerful. I also interviewed Cole in 2009 for my piece in the Times.

“As the sun rose on the morning of the fourth, the automatic weapons fire that had punctuated the night tapered off. Vehicles were smoldering along the main avenues,” Cole wrote to me.

Information from around the city was difficult to come by, as movement was pretty much shut down by the PLA, who had thousands of troops stationed throughout the city and checkpoints at all the main intersections. Stuart Franklin and I had been shooting much of this time together. We had photographed a number of wounded at the hospitals and tried to get as close to citizen-and-army encounters as possible without being detected or arrested.”

On the morning of the fifth, we were back on the vantage point of the Beijing Hotel balcony, trying to get a look into what was happening within the square itself. We had not been on the balcony very long when a line of at least 20 Armored Personnel Carriers left the square coming down Changan Avenue. At this point, they opened up on the crowd. I couldn’t tell if they were firing above the crowd or into them, but needless to say, it cleared the streets of the thousand or so persons there. The APC’s continued on down the avenue, followed not long after by the line of tanks.”

As the tanks neared the Beijing Hotel, the lone young man walked toward the middle of the avenue waving his jacket and shopping bag to stop the tanks. I kept shooting in anticipation of what I felt was his certain doom. But to my amazement, the lead tank stopped, then tried to move around him. But the young man cut it off again. Finally, the PSB (Public Security Bureau) grabbed him and ran away with him. Stuart and I looked at each other somewhat in disbelief at what we had just seen and photographed.”

I think his action captured peoples’ hearts everywhere, and when the moment came, his character defined the moment, rather than the moment defining him. He made the image. I was just one of the photographers. And I felt honored to be there.”

After taking the picture of the showdown, I became concerned about the PSB’s surveillance of our activities on the balcony. I was down to three rolls of film, with two cameras. One roll held the tank encounter, while the other had other good pictures of crowd and PLA confrontations and of wounded civilians at a hospital.”

I replaced the final unexposed roll into the one of the cameras, replacing the tank roll, and reluctantly left the other roll of the wounded in the other camera. I felt that if the PSB searched the room or caught me, they would look even harder if there was no film in the cameras.”

I then placed the tank roll in a plastic film can and wrapped it in a plastic bag and attached it to the flush chain in the tank of the toilet. I hid my cameras as best I could in the room. Within an hour, the PSB forced their way in and started searching the room. After about five minutes, they discovered the cameras and ripped the film out of each, seemingly satisfied that they had neutralized the coverage. They then forced me to sign a confession that I had been photographing during martial law and confiscated my passport.”

Sometime later, I was able to return to the room and retrieve the film, which I took over to the AP office and developed. Afterwards, David Berkwitz, who had been sent to Beijing as the Newsweek photo tech-photographer, transmitted the picture to Newsweek in time for our deadline.”

In my opinion, it is regretful that this image alone has become the iconic ‘mother’ of the Tiananmen tragedy. This tends to overshadow all the other tremendous work that other photographers did up to and during the crackdown. Some journalists were killed during this coverage and almost all risked being shot at one time or another. Jacques Langevin, Peter and David Turnley, Peter Charlesworth, Robin Moyer, David Berkwitz, Rei Ohara, Alon Reininger, Ken Jarecke and a host of others contributed to the fuller historical record of what occurred during this tragedy and we should not be lured into a simplistic, one-shot view of this amazingly complex event.’

Cole’s image was named the World Press Photo of the Year.

This is the un-cropped version of Cole’s photo. The addition of the burned-out bus and long row of tanks is fascinating. The light pole in the bottom right of the frame also gives some context to Widener’s position from the Beijing Hotel.

Sadly, Cole passed away at his home in Bali in 2019.

Magnum photographer Stuart Franklin, shooting for TIME, was shoulder to shoulder with Cole in the Beijing Hotel. Shadows dominate the left side, like storm clouds.

“I woke up in the Beijing Hotel to find Changan Avenue occupied by a line of students facing a line of soldiers and a column of tanks,” Franklin told me in a 2009 interview. “I was hunched down on a balcony on the fifth floor (I think). Three others were also on the balcony: Charlie Cole, a reporter for Actuel in France and one from Vanity Fair. I tried to photograph the whole series of events, but like any photographer working in film, I was always fearful of running out on frame 36!”

At some point, shots were fired and the tanks carried on down the road toward us, leaving Tiananmen Square behind, until blocked by a lone protester. I photographed the protester. He carried two shopping bags and remonstrated with the driver of the tank in an act of defiance. He then disappeared into the crowd after being led away from the tank by two bystanders.

The remainder of the day was spent trying to gain access to hospitals to determine how many had died or were wounded. In the two hospitals I could get access to, I found young Chinese — probably students — being treated on the floor of hospital corridors. It was mysterious that there were no dead. I understood later that the majority of the fatalities were taken to children’s hospitals in the city to avoid media attention. Chinese officials worked very hard obscure evidence of the massacre.

The film was smuggled out in a packet of tea by a French student and delivered to the Magnum office in Paris.”

While subtle, this vertical image by Franklin is captivating. “Tank Man” is nearly lost in the frame, quietly, peacefully, awaiting his fate.

The contact sheets are equally fascinating. The iconic frame is third row down, second from left…

Reuters photographer Arthur Tsang Hin Wah captured the moment Chinese tanks jostled for position in front of the lone man with the shopping bags.

“Gun shots can be heard coming in from east and west,” Tsang told me in 2009. “I felt unsafe going back to the square where the students stayed, so I went up to the 11th floor of the Beijing Hotel, where some of my press friends stayed.”

The square was clear but by now there were more than 100 tanks assembled. We watched people protesting near the hotel. Troops opened fire and killed many of them. We took pictures from the balcony while, across the street, police watched everything we did. Sometimes bullets hit the hotel rooms when the troops drove past and fired into the sky to scare off people.”

Rumors went around that they were going to clear the hotel. Many press people, especially the Chinese, packed up and left. At around noon. we heard the roar of tanks. More than 20 of them, in a big column, pulled out from the square and came our way. I loaded my Nikon F3HP with film and started shooting with a 300mm telephoto lens.”

Suddenly one of my friends shouted, ‘This guy is crazy!’ I saw from the viewfinder a man carrying two plastic shopping bags walk out onto the empty Changan Avenue from the sidewalk, blocking the tanks. The first tank pulled over a little but the man moved in the same direction, preventing it from advancing. I put on a 2x teleconverter and took a couple of tighter shots. Then the man climbed up the first tank and tried to talk to the soldiers inside. When he came down, four or five people came out from the sidewalk and pulled him away. He disappeared forever.”

Here is the un-cropped version of Tsang’s photo. He didn’t have the clearest view — but I appreciate how he worked around it. The 2x saved it.

Sing Tao Daily photographer Sin Wai Keung captured this epic landscape, which is often erroneously credited to Stuart Franklin. Sin told Reuters in 2014, “I didn’t think about the danger, or whether it would become an iconic image, as the news was still going on.”

After my story was published in The New York Times, I was contacted by Terril Jones, who said he shot this never-before-seen version from ground level. If you look closely, you can see “Tank Man” and the approaching tanks.

“I was extremely high strung by June 5 when I took this photo,” Jones revealed to me in 2009. “I had been running on little sleep since students began a hunger strike in Tiananmen Square on May 13, and I had been trading shifts with other AP reporters, staffing the square 24/7 for nearly three weeks.”

Adrenaline and the drive to stay close to the action took me back to the street on June 5. I was in front of the Beijing Hotel and I could hear tanks revving up and making their way toward us from Tiananmen. I went closer to the street and looked down Changan Avenue over several rows of parked bicycles when another volley of shots rang out from where the tanks were, and people began ducking, shrieking, stumbling and running toward me. I lifted my camera and squeezed off a single shot before retreating back behind more trees and bushes where hundreds of onlookers were cowering. I didn’t know quite what I had taken other than tanks coming toward me, soldiers on them shooting in my direction, and people fleeing.”

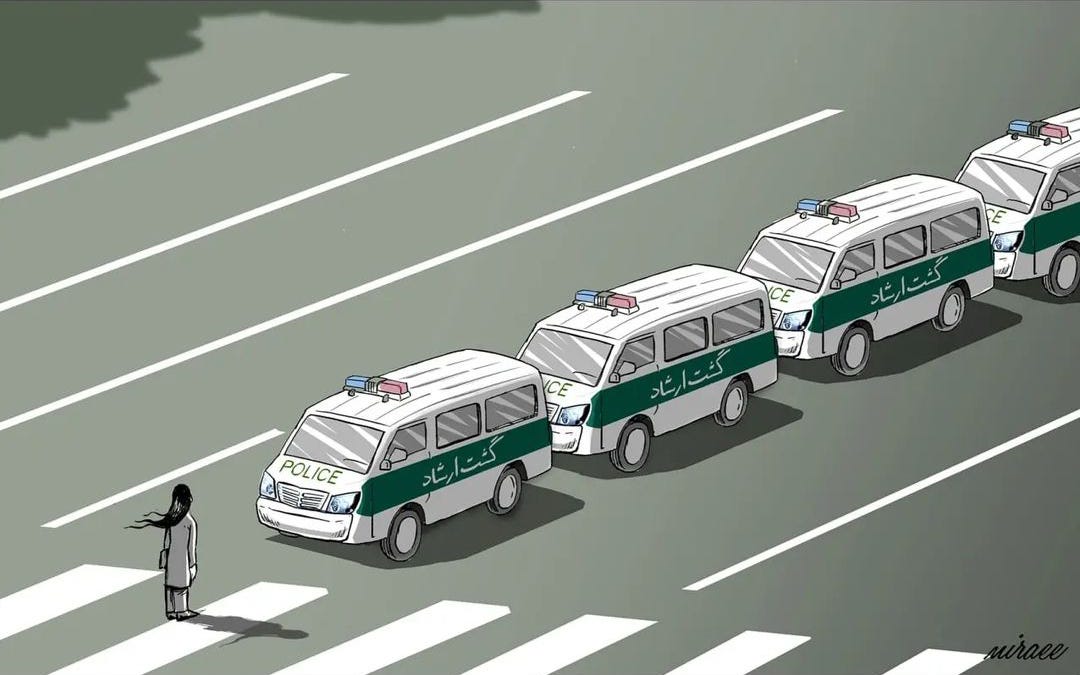

Over the years “Tank Man” has become a common trope for artists and illustrators. Jeff Widener’s photo is referenced in this artwork depicting Iran’s anti-veil protests by Iranian cartoonist Ali Miraee.

Norwegian political cartoonist also referenced Widener’s photo in this illustration for VG. Pretty smart. I appreciate the inclusion of the light pole in the bottom right.

And I loved this Widener “Tank Man” reference by Barry Blitt for Air Mail after Roe V. Wade was overturned.

This photo has been kicking around Reddit for a few years and I’d love to know more about it if anyone out there has further information. The comments are open to all on this post and, as always, feel free to reach out directly: patrickwitty@gmail.com.

The identity and fate of “tank man” remain unknown.